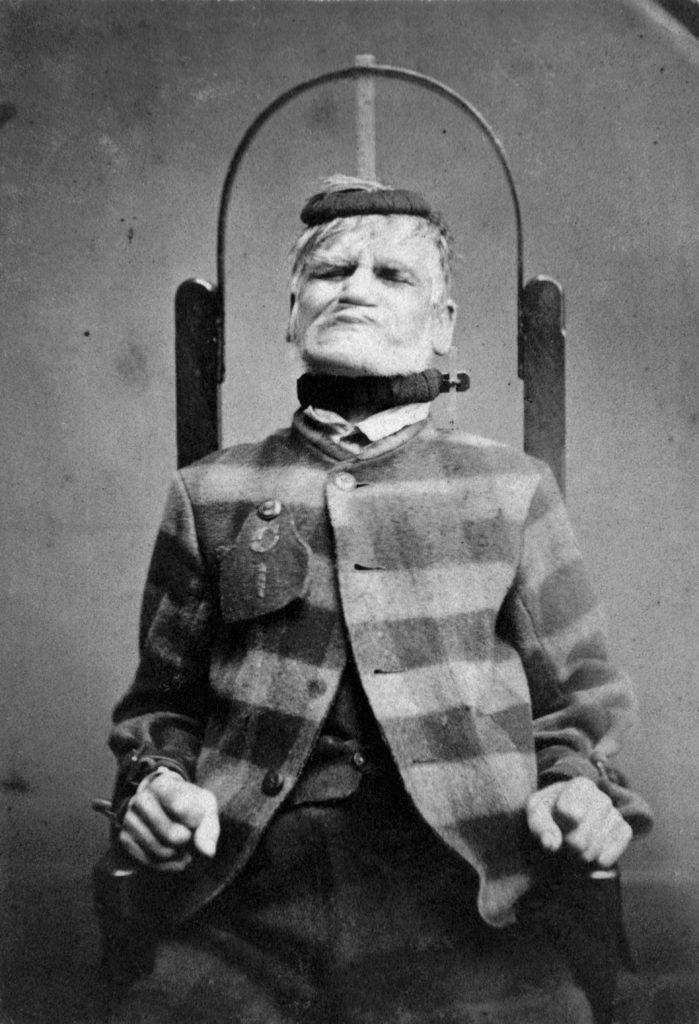

Man in restraint chair; by H. Clarke; 1869

Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images

A Farewell to Patriarchy

Women vs Feminism: Why We All Need Liberating from the Gender Wars, Joanna Williams, 2017, Emerald Publishing, 318pp., paperback, £14.99, reviewed by Ed Dutton

The sexual harassment scandal surrounding the film maker Harvey Weinstein has placed women’s rights squarely in the spotlight. The ‘Me too’ campaign, which has been spread across social media, seems to imply that women need ‘feminism’ more than ever. They are, at best, victims of testosterone-fuelled micro-aggressions: being stared at, leered at, objectified – in a way that would never happen if they were men. The feminist fight for equality will never be won until precisely these kinds of sexist behaviours are banished to the past.

However, in Women vs Feminism, education lecturer Joanna Williams insists, au contraire, that ‘There’s never been a better time to be a woman’ and that today’s feminism has nothing to do with achieving quality, because a calm analysis of the statistics indicates that it has already been pretty much achieved. Modern day feminism, Williams argues, is a totalitarian ideology, through which its proponents aim to achieve power. It aims to control and regulate behaviour – down to trivial details of what you can say, do, and even think – in pursuit of the eternal goal of ‘equality,’ which will never be reached. It persuades women that they are oppressed, that they are in danger from men, that they are discriminated against, and that being a woman severely limits their chances in a patriarchal world.

But, as Williams contends, this is simply untrue. In a lively text, she charts the history of women’s rights in the UK and the USA and shows that it certainly used to be true. Until as recently as the 1970s, women faced unequal pay, were regarded as expendable, had limited opportunities in certain professions, and the view that a woman’s place was in the home was still widespread. Williams concedes that, even now, there is pressure on women to take charge of the home and children. However, she demonstrates that females, in the UK for example, are, if anything, outperforming males. They perform considerably better in school exams and, in 2015, a British girl was 35% more likely to go to university than a British boy. In addition, Williams observes, the nature of school exams have changed – from a risky, winner-takes-all exam at the end of the course, to a series of modules requiring constant diligence – which seems to favour the modal female personality. Females are increasingly taking-up scientific subjects and they are hugely over-represented in the field of medicine.

Williams makes some insightful points about how feminists abuse statistics. For example, in the 1970s, only about a third of university students were female, which surely implies discrimination. However, a closer look reveals that the kind of subjects which are particularly female-dominated – such as nursing and teaching – were not generally covered by universities at the time. They were taught in separate colleges. Feminists bemoan the lack of women in science, because in a few scientific subjects their participation is low. But, overall, 45% of science students are female. Williams carefully explores areas such as the gender pay gap or the lack of women at the very top of certain professions. She shows that the pay gap is exaggerated through various forms of mathematical manipulation, such as including outlier high salaries in an average rather than comparing the median. Equally, she reveals that the under-representation of women in the highest echelons of the professions, in significant part, reflects the fact that they have only entered these professions in large numbers in the last few decades.

Equally, women are paid less than men in universities, but this is not a matter of discrimination. Men are more likely to teach science subjects, in which pay is higher than in the humanities. In looking at ‘the motherhood penalty’ – that women end up damaging their careers in order to have children – Williams highlights perhaps the key point. Modern feminists are obsessed with career women and they simply cannot understand that what many women want is choice. And this includes the choice to be wives and mothers if they wish.

The second half of the book is effectively a history and critique of the development of feminist ideology, which may act as a useful summary to any undergraduate who is unfamiliar with the topic. Use is made of a number of case studies – such as university pay – which are separated from the main text by being in grey boxes. This acts as useful aside from the narrative and helps to make the contents more digestible. Williams also explores conflicts within modern feminism, such as whether ‘trans women’ should be accepted as women at all, a view rejected, most prominently, by leading feminist Germaine Greer. Overall, she reaches the conclusion – bound to incite controversy – that we need to be ‘liberated’ from modern feminism as it is little more than an unending war which makes women wrongly believe that they are the subjects of oppression. Only when this liberation is achieved will both men and women ‘realize their full potential.’ This is a thoughtful critique of modern feminism and well worth putting on any student’s reading list.

Dr Edward Dutton is the author (with Bruce Charlton) of The Genius Famine: Why We Need Geniuses, Why They’re Dying Out and Why We Must Rescue Them, University of Buckingham Press, 2015

“Feminists” are divided in their policies e.g. over prostitution (“that’s wimmin, for yer”). But the main aim is not equal pay for equal output, but the transformation of females into units of industrial production instead of biological reproduction, and the breakdown of healthy sexual relations and the traditional family unit.

We need total liberation from the Equality Act 2010, its amendments, interpretations and enforcement, which are a major culmination in UK legislation of the “race-gender-class” revolution launched in the US by Marcuse and comrades several decades ago, and their “agenda-networking” successors. All this can be documented.

My only unfulfilled expectation is yet to see the nutritious “fetal matter” – i.e. unborn viable and sentient human beings – added as a special culinary delicacy on the metropolitan dinner party table, illustrated in full colour by The Guardian/Observer Food Monthly (spare copies of which, by the way, should be charitably sent as English literacy guides to perennially starving Africans before they float here).

I don’t suppose the Act will ever be abolished, because the so-called “Holocaust Education Centre” is being set up right next to Parliament to prevent just such “hateful” eventualities (q.v. David “Gay Matrimony” Cameron and Peter “Big Brother” Bazalgette on its real purpose).