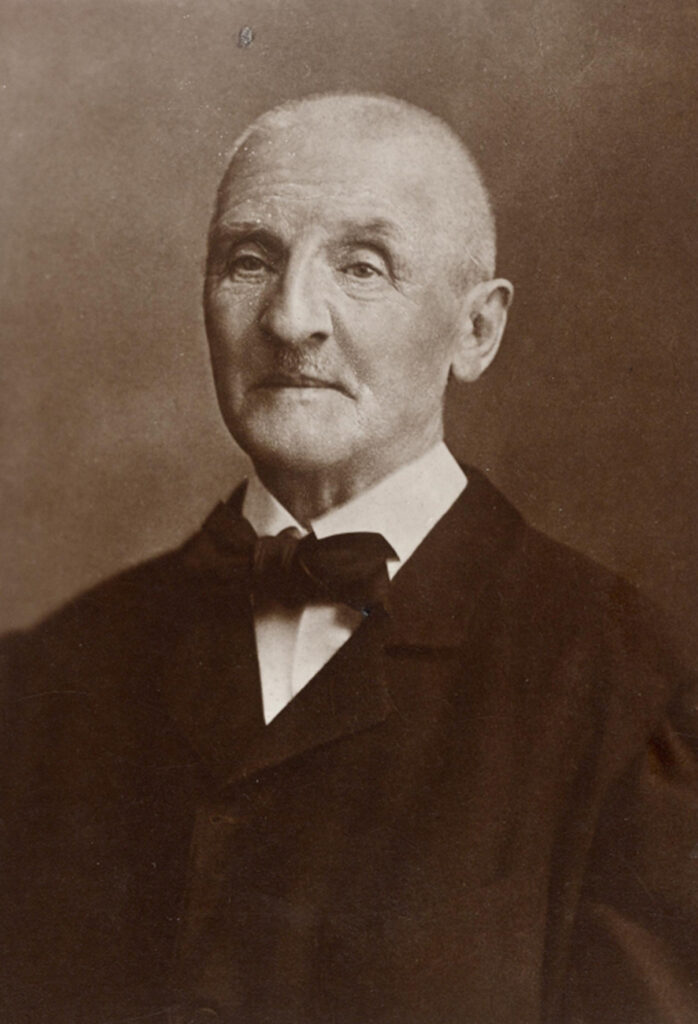

Philip Stanhope, 4th Earl of Chesterfield, portrait by Allan Ramsay, 1765, credit Wikipedia

The Elusive Earl of Chesterfield

By Richard Wendorf

Described by one of his contemporaries as “an eel too slippery to be held,” Lord Chesterfield has enjoyed the dubious distinction of serving as a lightning-rod for criticism twice over, first in the late Georgian period and more recently in our own century. In the mid-eighteenth century, on the other hand, many people were in fact distinctly afraid of Philip Dormer Stanhope, the 4th Earl of Chesterfield (1694-1773). Government ministers in the Commons, fellow politicians in the House of Lords, writers whose work was about to be assessed in polite circles, women who were aware of his reputation as a man of numerous “gallantries”: all had reason to fear the high standards, incisive wit, and personal displeasure of the Oscar Wilde or Sydney Smith of Georgian England. “Call it vanity, if you please, and possibly it was so,” he wrote to his son in one of the letters that gave him such posthumous fame, but his great object was always “to make every man I met with like me, and every woman love me.” But it didn’t turn out that way. Chesterfield’s wit, political views, and aura of genteel superiority made him an easy target for envy and jealousy – and occasionally downright hatred.

If one were to be judged by the quality and prominence of one’s enemies as well as one’s friends, then Chesterfield kept very good company indeed. He was despised by the King (George II, who was also his brother-in-law), the Queen (Caroline), the prime minister (Sir Robert Walpole), and the Queen’s closest friend (Lord Hervey). Walpole’s son Horace, who could be even more dismissive than Chesterfield, found him to be in turn amusing, deplorable, admirable as a prose stylist, and a failure as a father. For students of English literature, moreover, Chesterfield will always be known as the recipient of the most famous letter in the English language, written by an indignant Samuel Johnson, who felt that the Earl was behaving as if he had been the patron and long-time champion of his great Dictionary. “I hope it is no very cynical asperity,” Johnson wrote, “not to confess obligation where no benefit has been received, or to be unwilling that the Public should consider me as owing that to a Patron, which Providence has enabled me to do for myself.”

Remember, however, that it was Johnson who called upon Chesterfield in the mid-1740s in order to receive his approval for his heroic undertaking, for at the time the Earl was widely considered to be the arbiter of polite English usage. And what held true in the literary world was felt twice over within the circles of polite society, where Chesterfield was almost invariably described as the most elegant and well-mannered figure of his generation. In his periodical essays he defined the beau monde, described the importance of decorum, distinguished between civility and good-breeding, and ridiculed fellow aristocrats who focused so much of their energies on determining who was “of birth” or “of no birth.” In some ways Chesterfield could be unusually egalitarian, repeatedly sympathizing with the poor – laborers, servants, beggars – but then (as we might say) he could well afford to do so. As the Poet Laureate, Colley Cibber, astutely noted, “the only advantage he makes of his superiority is that by always waiving it himself, his inferior finds he is under the greater obligation not to forget it.”

But this sense of superiority – of intelligence, taste, genteel behavior, and even his noble birth – did not always come easily to him. His father thought that he was a useless fop and paid little attention to him. His mother more or less disappeared during his childhood, when he was raised by his grandmother, the widow of the Marquess of Halifax, the great “trimmer” of Restoration politics. And even though he was pampered by tutors, happily submerged in Latin and classical Greek, he felt himself to be socially awkward when he finally made his way in the polite world. And yet this same hesitant, stammering young man would become the epitome of the well-mannered Englishman, literally (if unwittingly) writing his generation’s book on the correct forms of etiquette – and on the norms of civility – during the Georgian period. In spite of his hesitancy and “embarrassment” when young, he would eventually know every monarch, senior politician, and prominent writer in England, often on an intimate basis. He would marry the daughter of George I, become a savvy politician and orator, and refuse the offer of a dukedom when resigning the seals as Secretary of State. And yet it was, as he told his son, an uphill battle.

For Chesterfield suffered from a serious disability – his increasingly profound deafness – and from what he perceived as a significant physical liability, which was articulated most famously by George II. The Earl was, the King told Lord Hervey, “a little tea-table scoundrel, that tells little womanish lies to make quarrels in families, and tries to make women lose their reputations, and make their husbands beat them, without any object but to give himself airs; as if anybody could believe a woman could like a dwarf-baboon.” Hervey was no less critical: “With a person as disagreeable as it was possible for a human figure to be without being deformed, he affected following many women of the first beauty and the most in fashion, and, if you would have taken his word for it, not without success.” He was, Hervey continued, “very short, disproportioned, thick, and clumsily made; had a broad, rough-featured, ugly face, with black teeth, and a head big enough for a Polyphemus.” People at court called him a stunted giant. William Pulteney, later the Earl of Bath, referred to him as “the little chattering cur.” His voice was harsh and croaking; Lady Cowper described it as “a shrill scream.”

Chesterfield was painfully aware of his short stature. He mentioned it in letter after letter, sometimes complaining that the Stanhopes were “a tribe little above pigmies.” Perhaps the most telling moment in Chesterfield’s running commentary on his height was when he wrote to his son, also Philip Stanhope, in 1752 about his early desire “to make every man I met with like me, and every woman love me.” Here is the crucial rest of the quotation: “I often succeeded; but why? By taking great pains; for otherwise I never should; my figure by no means intitled me to it, and I had certainly an up-hill game.” This is an exhortation, of course, for Philip to work harder, to replicate his father’s years of self-improvement and self-fashioning: “Dress, address, and air, would become your best countenance, and make your little figure pass very well.” But what is intriguing here is both Chesterfield’s silence about his own entitlement as the inheritor of an earldom, and his insistence, instead, that his own diminutive figure did not entitle him to success in politics or in the beau monde. Such success would only come with education, application, and attention to the niceties of life. Saddled with certain physical limitations, the Earl would have to compensate for his perceived liability by becoming more able than his contemporaries: in his mastery of European languages and history, his conversational wit, his manners, and his external polish. As he told his godson, he began life with “an insatiable thirst” for popularity, applause, and admiration. But these rewards would not come to him as a matter of course, based either on his birth and rank or on his figure and countenance.

Chesterfield augmented his standing within the beau monde by making use of his family connections, marrying the King’s daughter, and building the largest private house in London. These manoeuvres held him in good stead within the rough-and-tumble world of Hanoverian politics as well. His four-year term as Ambassador to The Hague was a considerable success, cementing the Second Treaty of Vienna and arranging for the marriage of Anne, the Princess Royal, with the Prince of Orange. When he returned to London in 1732, with a pregnant mistress (Elizabeth du Bouchet) in tow, he could have expected that he was well on his way into the Cabinet. But in the following year he broke decisively with Robert Walpole’s ministry over the infamous Excise Bill and found himself in vociferous opposition for the next twelve years. He fought Walpole tooth and nail over the Licensing Act, which he saw as a form of political repression as well as an attack on freedom of the press; and he gained a considerable following in the Lords as he became a gifted speaker (he was so successful there that Walpole and the King elevated Hervey to the upper house so that he could duel with him).

Finally, in 1745, he entered the Cabinet as the King’s Viceroy in Ireland, a relatively undemanding post that Chesterfield undertook with great seriousness, endearing himself to the Irish while simultaneously quelling revolutionary spirit during the dangerous Jacobite rebellion. He returned to London in great favour the following year and became one of the two Secretaries of State, a position that he had long coveted and whose powers, he soon discovered, had irritatingly strict limits. Depressed, physically exhausted, and fed up with the fastidious meddling of his fellow Secretary, his kinsman the Duke of Newcastle, he resigned the seals in 1748 and focused his sights on retirement and his architectural projects. He had, however, one final political goal in mind, the adoption of the Gregorian calendar, which belatedly aligned Britain with most of the countries in Europe. Chesterfield initiated the legislation, campaigned for it in Parliament, and saw it adopted in 1751 and implemented in September 1752. The Earl was characteristically casual, if not flippant, in describing his accomplishment to his son, but few legislative acts during the Hanoverian period had as many far-reaching consequences as his did. Britain now saw itself as “New Style” rather than “Old.” Chesterfield had therefore placed himself in a highly unusual position, with one foot in the beau monde and the other in Whitehall and the Lords. Looking back from the nineteenth century, Macaulay understood just how extraordinary this situation was: Chesterfield embodied “what no person in our time has been or can be, a great political leader and at the same time the acknowledged chief of the fashionable world; at the head of the House of Lords and at the head of the ton; Mr. Canning and the Duke of Devonshire in one.”

If Chesterfield had died in the 1750s, he would have been celebrated as a politician and as a wit. If his letters to his son had not been published a year after he died, he would probably have been remembered less as a statesman and more as an essayist and exemplar of aristocratic taste. He would have enjoyed a diminished reputation, but he would certainly not have been forgotten. But his letters were published in 1774 – and all hell broke loose. The collection of well over 400 letters went through multiple printings; they were carefully annotated by Horace Walpole; they were anthologized as guides to polite conduct; they were parodied and satirized; they generated paper wars and tea-table debates; they became, in short, the publishing sensation of the final quarter of the century. Those who had feared Chesterfield now had their revenge, and it was served cold by bluestockings and evangelicals alike.

Chesterfield’s modern critics have paid little attention to late eighteenth-century charges of irreligiosity, nor have they concerned themselves with issues of libertinism or immorality. But echoes of the original shrieks of horror and disdain still remain: not to the point of canceling or de-platforming the Earl from critical discourse, but by making him a lightning rod within discussions of civility in the eighteenth century. Some of these critical voices are almost gratuitous in their remarks, as when Adam Nicolson casually dismisses “the superbly obnoxious Lord Chesterfield . . . the great eighteenth-century apostle of deceit” in his study of the English gentry, or when the historian Wilfred Prest refers to the “elegant cynicism” of the “snobbish earl of Chesterfield.” More troubling are the remarks by modern commentators on matters of etiquette and social decorum. Michael Curtin argues that the “elaborate care Chesterfield devoted to manners seemed to be entirely selfish and without concern for the good of the community,” whereas Chesterfield makes precisely this connection in his essays and letters. Good manners, he wrote, “are, to particular societies, what good morals are to society in general; their cement and their security.” Even Keith Thomas, in his recent study of civility, falls into the common trap of arguing that “Chesterfield was more concerned with external appearances than with internal sentiment.” But when the Earl famously pronounced that “manner is all,” he did so within a specific context, advising his son that intelligence, learning, and even virtue itself would come to nothing if they were not conveyed in a suitably agreeable and gracious manner. This was Chesterfield’s understanding of the social contract: in order to be successful in one’s profession, or to flourish within polite society, one needed to accede to the social codes that were firmly in place. If Chesterfield reiterated this point ad nauseum in his letters, it was because he was afraid that his son would never fully embrace “the graces.” Chesterfield was keenly aware of the relationship between external appearance and what lies within, and one of his most important observations occurs in a letter to his son of 1749: “The world is taken by the outside of things, and we must take the world as it is; you nor I cannot set it right.”

If Chesterfield has not quite yet reached the realm of noli tangere in recent critical discourse, he has certainly been approached with caution and suspicion – and for good reason. Some of his views remain problematical and some are clearly repugnant. It is commonly said, for instance, that Chesterfield did not think much of women. It would be more precise to say that his written comments about women are often condescending, dismissive, or flagrantly misogynistic. It would also be accurate to say that he thought a good deal about women, that he enjoyed writing about them, writing to them, hearing from them, and socializing with them. One of the complications in trying to understand Chesterfield is that he could be brutal in what he said about women in general and yet be kind, attentive, and respectful when he wrote to individual women or interacted with them. His generalizations about women are legion, and often derisory, as in his notorious description of them as “but children of a larger growth.” They “have an entertaining tattle, and sometimes wit; but for solid, reasoning good sense, I never in my life knew one that had it, or who reasoned or acted consequently for four-and-twenty hours together.” A man only trifles with them, “plays with them, humours and flatters them, as he does with a sprightly, forward child.”

Chesterfield’s misogyny – but surely only in part – was based on his fairly low estimation of humankind in general, which had been confirmed during his many years of service at the Court of George II, as an ambassador on the Continent, and as one of the three senior members of government. He was not a misanthrope, however; he was ready to accept and admire the talents and good graces of his contemporaries; but he saw himself as a realist, a pragmatist, someone who had a keen sense of how the world worked. He wrote to his son that “I have been behind the scenes, both of pleasure and business. I have seen all the coarse pulleys and dirty ropes, which exhibit and move all the gaudy machines; and I have seen and smelt the tallow-candles which illuminate the whole decoration, to the astonishment and admiration of the ignorant audience.” He also understood the fragility and artificiality of the conventions that underpinned polite civil discourse and polite behaviour, including dissimulation as a mild form of hypocrisy. Polite society was predicated on the art of pleasing, of speaking and acting – and bowing, walking, and dancing – in a certain manner, a manner based on complaisance and accommodation rather than on blunt honesty, let alone direct confrontation.

What held true for social interaction was also essential for making one’s way in the professions, especially for a son whose illegitimacy closed off so many natural avenues for advancement. Young Philip must learn to master the “inoffensive arts,” including various forms of flattery, and he must learn to be the absolute master of his countenance and passions. “Volto sciolto con pensieri stretti” is the motto that Chesterfield embedded in letter after letter to his son: maintain an open face but keep your thoughts hidden. Discover, moreover, what lies behind the mask of those with whom you would socialize or work. “Penetrate” their hidden recesses; find out what their ruling passions are, for by knowing your colleagues’ strengths and weaknesses you will be able to further your country’s business as well as your own career.

Chesterfield was known to his contemporaries as a master of irony – in his essays, his speeches in the Lords, his elegant put-downs – and yet he could not have anticipated the ironies that would characterize his own life. His letters are filled with a roll-call of the complaints from which he suffered throughout his lifetime, particularly from deafness during his final two decades, and yet he lived to be 81, a very ripe old age at the time. Having told his son and his friends that he expected to die at any moment, beginning in the 1750s, he outlived almost all of his illustrious contemporaries. Although he enjoyed certain claims to fame during his lifetime, he could not have imagined the posthumous fame and notoriety his name would evoke once the letters to his son had been published. And although his ambition was to become one of the leading politicians of his era, he has instead gone down in history as one of the most important cultural figures of his age.

What then remains of the Earl’s legacy? Chesterfield House was razed to the ground in the 1930s to make way for an undistinguished pile of expensive flats. His country retreat in Blackheath became a tea house at the nadir of its existence and is now kept on life-support as the Ranger’s House by English Heritage. Chesterfield’s accomplishments and speeches as a politician were soon eclipsed by the those of Burke and Fox, Pitt and Peel. The hundreds of French and Italian words he introduced into the English language – including etiquette, dilettante, gauche, picnic, brochure, rouge, sang-froid, coterie, hors de combat – have long been fully absorbed within the King’s English. His maxims and bon mots, which used to be heavily anthologized, are now only rarely invoked, and the one most frequently cited, under the heading of “sex” – “the pleasure is momentary, the position ridiculous, the expense damnable” – is almost certainly not of his coinage, although he probably would not have denied it.

What does remain is his literary œuvre – the letters, essays, and character sketches – and a reputation for refined taste that has never entirely disappeared. Even if you live in America, you can reside in Chesterfield County, Virginia, paddle on Lake Chesterfield in Missouri, wear a Chesterfield topcoat with its velvet collar, sit on a Chesterfield sofa, sport Chesterfield cufflinks and tie pin, lather yourself using a Chesterfield shaving brush, drink a Chesterfield lager, use a Chesterfield lighter to smoke a Chesterfield cigarette, and follow the actress Jennifer Anniston on social media. “Jen” has named her latest dog Lord Chesterfield and, needless to say, he is a celebrity, too. The Chesterfield name has, in fact, been adopted by more American brands than that of any other aristocratic British family. These may seem garish forms of tribute but, after so much of his potential legacy has disappeared, they continue to reflect the Earl’s reputation for elegant taste centuries after his death.

Professor Richard Wendorf is the author of Chesterfield: the Perils of Politeness (forthcoming) and Sir Joshua Reynolds: The Painter in Society, which won the biography prize from the American society for Eighteenth-Century Studies

Like this:

Like Loading...