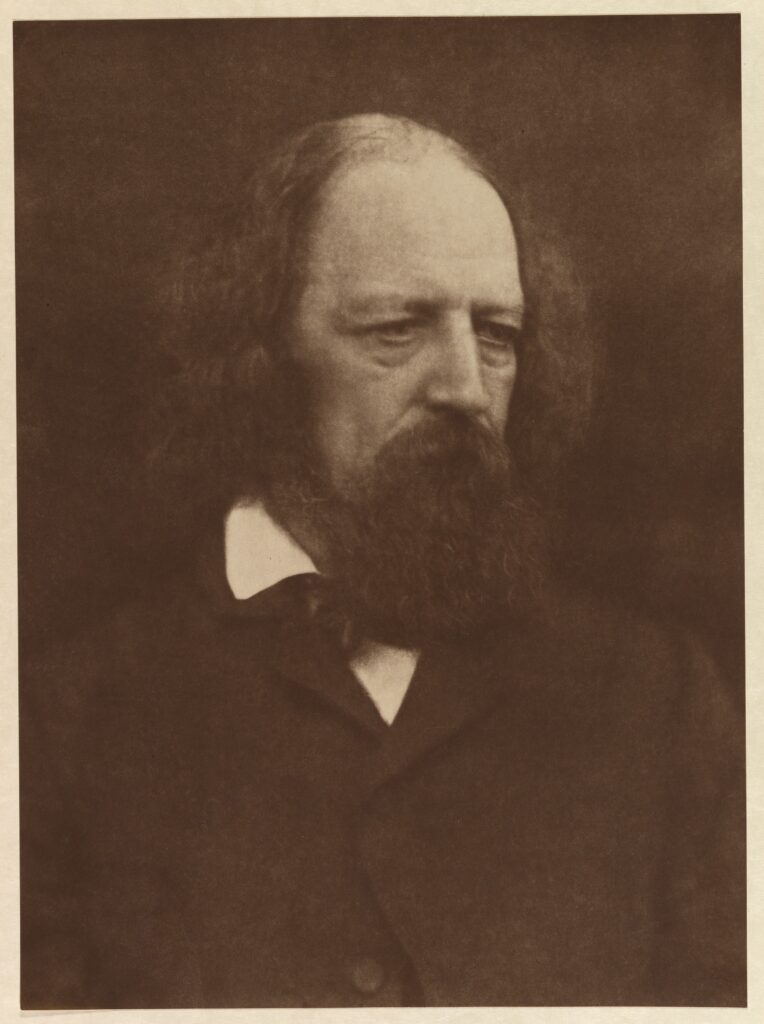

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Poems by Alfred Tennyson

Reviewed by John Wilson Croker (from Spring 1833)

EDITOR’S NOTE: The original QR always disliked the new poetry that emerged in the first half of the 19th century as a reaction against the stately poetry of the Augustan Age. The QR’s first editor, William Gifford, had first made his literary mark with a long poem called The Baviad, a vitriolic attack against the Della Cruscans, a group of sentimentalist poets briefly in vogue at the turn of the 18th/19th centuries. Later, the journal was even blamed by Lord Byron for the death of John Keats, whose Endymion was savaged by John Wilson Croker as being sentimental, bathetic, vulgar and implicitly subversive. Keats was termed a “Cockney poet” – and Croker appears to have regarded Tennyson in the same light. Croker (1750-1857) was one of the QR’s liveliest contributors for over 20 years, in between working as an Irish MP and a highly effective Secretary to the Admiralty. Apart from his QR writings, he is also credited with having introduced the word “Conservatives” into British politics. He is thought to be the model for “Rigby” in Benjamin Disraeli’s novel Coningsby. The first half of this review appeared in the print edition of the Autumn 2009 QR. DT

This is, as some of his marginal notes intimate, Mr Tennyson’s second appearance. By some strange chance we have never seen his first publication, which, if it at all resembles its younger brother, must be by this time so popular that any notice of it on our part would seem idle and presumptuous; but we gladly seize this opportunity of repairing an unintentional neglect, and of introducing to the admiration of our more sequestered readers a new prodigy of genius – another and a brighter star of that galaxy or milky way of poetry of which the lamented Keats was the harbinger; and let us take this occasion to sing our palinode on the subject of Endymion: We certainly did not discover in that poem the same degree of merit that its more clear-sighted and prophetic admirers did. We did not foresee the unbounded popularity which has carried it through we know not how many editions; which has placed it on every table; and, what is still more unequivocal) familiarized it in every mouth. All this splendour of fame, however, though we had not the sagacity to anticipate, we have the candour to acknowledge; and we request that the publisher of the new and beautiful edition of Keats’s works now in the press, with graphic illustrations by Calcott and Turner, will do us the favour and the justice to notice our conversion in his prolegomena.

Warned by our former mishap, wiser by experience, and improved, as we hope, in taste, we have to offer Mr. Tennyson our tribute of unmingled approbation, and it is very agreeable to us, as well as to our readers, that our present task will be little more than the selection, for their delight, of a few specimens of Mr. Tennyson’s singular genius, and the venturing to point out, now and then, the peculiar brilliancy of some of the gems that irradiate his poetical crown.

A prefatory sonnet opens to the reader the aspirations of the young author, in which, after the manner of sundry poets, ancient and modern, he expresses his own peculiar character, by wishing himself to be something that he is not. The amorous Catullus aspired to be a sparrow; the tuneful and convivial Anacreon wished to be a lyre and a great drinking cup; a crowd of more modern sentimentalists have desired to approach their mistresses as flowers, tunicks, sandals, birds, breezes, and butterflies – all poor conceits of narrow-minded poetasters! Mr. Tennyson (though he, too, would, as far as his true-love is concerned, not unwillingly be “an earring”, “a girdle”, and “a necklace”, p. 45) in the more serious and solemn exordium of his works ambitions a bolder metamorphosis – he wishes to be – a river!

“Mine be the strength of spirit fierce and free,

Like some broad river rushing down alone”

rivers that travel in company are too common for his taste.With the self-same impulse wherewith he was thrown – a beautiful and harmonious line

“From his loud fount upon the echoing lea:

Which, with increasing might, doth forward flee”

Every word of this line is valuable – the natural progress of humanambition is here strongly characterized – two lines ago he would have been satisfied with the self-same impulse – but now he must haveincreasing might; and indeed he would require all his might to accomplish his object of fleeing forward, that is, going backwards and forwards at the same time. Perhaps he uses the word flee for flow; which latter he could not well employ in this place, it being, as we shall see, essentially necessary to rhyme to Mexico towards the end of the sonnet – as an equivalent to flow he has, therefore, with great taste and ingenuity, hit on the combination of forward flee –

“…………doth forward flee

By town, and tower, and hill, and cape, and isle,

And in the middle of the green salt sea

Keeps his blue waters fresh for many a mile.”

A noble wish, beautifully expressed, that he may not be confounded with the deluge of ordinary poets, but, amidst their discoloured and briny ocean, still preserve his own bright tints and sweet savor. He may be at ease on this point – he never can be mistaken for any one else. We have but too late become acquainted with him, yet we assure ourselves that if a thousand anonymous specimens were presented to us, we should unerringly distinguish his by the total absence of any particle of salt. But again) his thoughts take another turn, and he reverts to the insatiability of human ambition – we have seen him just now content to be a river, but as he flees forward, his desires expand into sublimity, and he wishes to become the great Gulf-stream of the Atlantic.

“Mine be the power which ever to its sway

Will win the wise at once”

We, for once, are wise, and he has won us

“Will win the wise at once; and by degrees

May into uncongenial spirits flow,

Even as the great gulphstream of Florida

Floats far away into the Northern seas

The lavish growths of southern Mexico”

And so concludes the sonnet. The next piece is a kind of testamentary paper, addressed “To _________”, a friend, we presume, containing his wishes as to what his friend should do for him when he (the poet) shall be dead – not, as we shall see, that he quite thinks that such a poet can die outright.

“Shake hands, my friend, across the brink

Of that deep grave to which I go.

Shake hands once more; I cannot sink

So far – far down, but I shall know

Thy voice, and answer from below!”

Horace said “non omnis moriar”, meaning that his fame should survive – Mr. Tennyson is still more vivacious, “non omnino moriar” – I will not die at all; my body shall be as immortal as my verse, and however low I may go, I warrant you I shall keep all my wits about me – therefore

“When, in the darkness over me,

The four-handed mole shall scrape,

Plant thou no dusky cypress tree,

Nor wreath thy cap with doleful crape,

But pledge me in the flowing grape.”

Observe how all ages become present to the mind of a great poet; and admire how naturally he combines the funeral cypress of classical antiquity with the crape hatband of the modern undertaker. He proceeds:

“And when the sappy field and wood

Grow green beneath the showery gray,

And rugged barks begin to bud,

And through damp holts, newflushed with May,

Ring sudden laughters of the jay!”

Laughter, the philosophers tell us, is the peculiar attribute of man – but as Shakspeare found “tongues in trees and sermons in stones”, this true poet endows all nature not merely with human sensibilities but with human functions – the jaylaughs, and we find, indeed, a little further on, that the woodpecker laughs also; but to mark the distinction between their merriment and that of men, both jays and woodpeckers laugh upon melancholy occasions. We are glad, moreover, to observe, that Mr. Tennyson is prepared for, and therefore will not be disturbed by, human .laughter, if any silly reader should catch the infection from the woodpeckers and jays.

“Then let wise Nature work her will,

And on my clay her darnels grow,

Come only when the days are still,

And at my head-stone whisper low,

And tell me”

Now, what would an ordinary bard wish to be told tinder such circumstances? – why, perhaps, how his sweetheart was, or his child, or his family, or how the Reform Bill worked, or whether the last edition of the poems had been sold – papæ! Our genuine poet’s first wish is

“And tell me—if the woodbines blow!”

When, indeed, he shall have been thus satisfied as to the woodbines, (of the blowing of which in their due season he may, we think, feel pretty secure,) he turns a passing thought to his friend – and another to his mother

“If thou art blest, my mother’s smile

Undimmed”

but such inquiries, short as they are, seem too commonplace, and he immediately glides back into his curiosity as to the state of the weather and the forwardness of the spring

“If thou art blessed – my mother’s smile

Undimmed—if bees are on the wing?”

No, we believe the whole circle of poetry does not furnish such another instance of enthusiasm for the sights and sounds of the vernal season! The sorrows of a bereaved mother rank after the blossoms of thewoodbine, and just before the hummings of the bee; and this is all that he has any curiosity about; for he proceeds

“Then cease, my friend, a little while

That I may”

“send my love to my mother” or “give you some hints about bees, which I have picked up from Aristæus, in the Elysian Fields” or “tell you how I am situated as to my own personal comforts in the world below”? – oh no

“That I may hear the throstle sing

His bridal song – the boast of spring.

Sweet as the noise, in parched plains,

Of bubbling wells that fret the stones, (If any sense in me remains)

Thy words will be – thy cheerful tones

As welcome to – my crumbling bones!’—p. 4.

“If any sense in me remains!” This doubt is inconsistent with the opening stanza of the piece, and, in fact, too modest; we take upon ourselves to re-assure Mr Tennyson, that, even after he shall be dead and buried, as much sense will still remain as he has now the good fortune to possess.

We have quoted these two first poems in extenso, to obviate any suspicion of our having made a partial or delusive selection. We cannot afford space – we wish we could – for an equally minute examination of the rest of the volume, but we shall make a few extracts to show – what we solemnly affirm – that every page teems with beauties hardly less surprising.

The Lady of Shalott is a poem in four parts, the story of which we decline to maim by such an analysis as we could give, but it opens thus –

“On either side the river lie

Long fields of barley and of rye,

That clothe the wold and meet the sky-‑

And through the field the road runs by.

”The Lady of Shalott was, it seems, a spinster who had, under some unnamed penalty, a certain web to weave.

“Underneath the bearded barley,

The reaper, reaping late and early,

Hears her ever chanting cheerly,

Like an angel singing clearly,

No time has she to sport or play,

A charmed web she weaves always

A curse is on her if she stay

Her weaving either night or day.

She knows not”

Poor lady, nor we either –

“She knows not what that curse may be,

Therefore she weaveth steadily;

Therefore no other care has she,

The Lady of Shalott.”

A knight, however, happens to ride past her window, coming “from Camelot”

“From the bank, and from the river,

He flashed into the crystal mirror –

Tirra lirra, tirra lirra,” (lirrar?)

Sang Sir Launcelot” – p15

The lady stepped to the window to look, at the stranger, and forgot for an instant her web: the curse fell on her, and she died; why, how, and wherefore, the following stanzas will clearly and pathetically explain

“A long drawn carol, mournful, holy,

She chanted loudly, chanted lowly,

Till her eyes were darkened wholly,

And her smooth face sharpened slowly,

Turned to towered Camelot

.For ere she reached upon the tide

The first house on the water side,

Singing in her song she died,

The Lady of Shalott!

Knight and burgher, lord and dame,

To the planked wharfage came;

Below the stern they read her name,

The Lady of Shalott” –.p19

We pass by two – what shall we call them? – tales, or odes, or sketches, entitled “Mariana in the South” and “Eleanore”, of which we fear we could make no intelligible extract, so curiously are they run together into one dreamy tissue – to a little novel in rhyme, called “The Miller’s Daughter”. Miller’s daughters, poor things, have been so generally betrayed by their sweethearts, that it is refreshing to find that Mr Tennyson has united himself to his miller’s daughter in lawful wedlock, and the poem is a history of his courtship and wedding. He begins with a sketch of his own birth, parentage, and personal appearance

“My father’s mansion, mounted high,

Looked down upon the village-spire;

I was a long and listless boy,

And son and heir unto the Squire.”

But the son and heir of Squire Tennyson often descended from the “mansion mounted high” and

“I met in all the close green ways,

While walking with my line and rod,”

A metonymy for ‘rod and line’ –

“The wealthy miller’s mealy face,

Like the moon in an ivytod.

He looked so jolly and so good

While fishing in the mill-dam water,

I laughed to see him as he stood,

And dreamt not of the miller’s daughter.” – p3

3He, however, soon saw, and, need we add, loved the miller’s daughter, whose, countenance, we presume, bore no great resemblance either to the “mealy face” of the miller, or “the moon in an ivy-tod”; and we think our readers will be delighted at the way in which the impassioned husband relates to his wife how his fancy mingled enthusiasm for rural sights and sounds, with a prospect of the less romantic scene of her father’s occupation.

“How dear to me in youth, my love,

Was everything about the mill;

The black, the silent pool above,

The pool beneath that ne’er stood still;

The meal-sacks on the whitened floor,

The dark round of the dripping wheel,

The very air about the door,

Made misty with the floating meal!” – p36

The accumulation of tender images in the following lines appears not less wonderful:

“Remember you that pleasant day

When, after roving in the woods

‘Twas April then) I came and lay

Beneath those gummy chestnut-buds?

A water-rat from off the bank

Plunged in the stream.

With idle care,

Downlooking through the sedges rank,

I saw your troubled image there.

If you remember, you had set

Upon the narrow casement edge,

A long green box of mignonette,

And you were leaning on the ledge.”

The poet’s truth to Nature in his “gummy” chestnut-buds, and to Art in the “long green box” of mignonette – and that masterly touch of likening the first intrusion of love into the virgin bosom of the Miller’s daughter to the plunging of a water-rat into the mill-dam – these are beauties which, we do not fear to say, equal anything even in Keats.

We pass by several songs, sonnets, and small pieces, all of singular merit, to arrive at a class, we may call them, of three poems derived from mythological sources – Œnone, the Hesperides, and the Lotos-eaters. But though the subjects are derived from classical antiquity, Mr. Tennyson treats them with so much originality that he makes them exclusively his own. Œnone, deserted by“Beautiful Paris, evilhearted Paris”sings a kind of dying soliloquy addressed to Mount Ida, in a formula which is sixteen times repeated in this short poem – “Dear mother Ida, hearken ere I die”.

She tells her “dear mother Ida” that when evilhearted Paris was about to judge between the three goddesses, he hid her (Œnone) behind a rock, whence she had a full view of the naked beauties of the rivals, which broke her heart.

Dear mother Ida, hearken ere I die

It was the deep mid noon: one silvery cloud

Had lost his way among the pined hills:

They came – all three –the Olympian goddesses.

Naked they came

* * * * *

“How beautiful they were! too beautiful

To look upon; but Paris was to me

More lovelier than all the world beside.

O mother Ida, hearken ere,I die.” – p56

In the place where we have indicated a pause, follows a description, long, rich, and luscious – Of the three naked goddesses ? Fye

for shame – no – of the “lily flower violet-eyed” and the “singing pine”, and the “overwandering ivy and vine”, and “festoons” and

”gnarled boughs” and “tree tops” and “berries” and “flowers”,

and all the inanimate beauties of the scene. It would be unjust to theingenuus pudor of the author not to observe the art with which he has veiled this ticklish interview behind such luxuriant trellis-work, and it is obvious that it is for our special sakes he has entered into these local details, because if there was one thing which “mother Ida” knew better than another, it must have been her own bushes and brakes. We then have in detail the tempting speeches of, first –

“The imperial Olympian,

With arched eyebrow smiling sovranly,

Full-eyed Here;”

secondly of Pallas –

“Her clear and barèd limbs

O’er-thwarted with the brazen-headed spear,”and thirdly –

“Idalian Aphrodite ocean-born,

Fresh as the foam, new-bathed in Paphian wells”

for one dip, or even three dips in one well, would not have been enough on such an occasion – and her succinct and prevailing promiseof“The fairest and most loving wife in Greece;”upon evil-hearted Paris’s catching at which prize, the tender and chaste Œnone exclaims her indignation, that she herself should not be considered fair enough, since only yesterday her charms had struck awe into

“A wild and wanton pard,

Eyed like the evening star, with playful tail”

and proceeds in this anti-Martineau rapture“

’Most loving is she?’

Ah me! my mountain shepherd, that my arms

Were wound about thee, and my hot lips prest

Close – close to thine in that quick-falling dew

Of fruitful kisses…….

Dear mother Ida! hearken ere I die!” – p62

After such reiterated assurances that she was about to die on the spot, it appears that Œnone thought better of it, and the poem concludes with her taking the wiser course of going to town to consult her swain’s sister, Cassandra – whose advice, we presume, prevailed upon her to live, as we can, from other sources, assure our readers she did to a good old age.In the “Hesperides” our author, with great judgment, rejects the common fable, which attributes to Hercules the slaying of the dragon and the plunder of the golden fruit. Nay, he supposes them to have existed to a comparatively recent period – namely, the voyage of Hanno, on the coarse canvas of whose log-book Mr. Tennyson has judiciously embroidered the Hesperian romance. The poem opens with a geographical description of the neighbourhood, which must be very clear and satisfactory to the English reader; indeed, it leaves far behind in accuracy of topography and melody of rhythm the heroics of Dionysius Periegetes.

“The north wind fall’n, in the new-starred night.”

Here we must pause to observe a new species of metabolė with which Mr. Tennyson has enriched our language. He suppresses the E in fallen,where it is usually written and where it must be pronounced, and transfers it to the word new-starrèd, where it would not be pronounced if he did not take due care to superfix a grave accent. This use of the grave accent is, as our readers may have already perceived, so habitual with Mr. Tennyson, and is so obvious an improvement, that we really wonder how the language has hitherto done without it. We are tempted to suggest, that if analogy to the accented languages is to be thought of, it is rather the acute than the grave which should be employed on such occasions; but we speak with profound diffidence; and as Mr. Tennyson is the inventor of the system, we shall bow with respect to whatever his final determination may be,

“The north wind fall’n, in the new-starrèd night

Zidonian Hanno, voyaging beyond

The hoary promontory of Solöe,

Past Thymiaterion in calmed bays.”

We must here note specially the musical flow of this last line, which is the more creditable to Mr. Tennyson, because it was before the tuneless names of this very neighbourhood that the learned continuator of Dionysius retreated in despair, but Mr. Tennyson is bolder and happier

“Past Thymiaterion in calmed bays,

Between the southern and the western Horn,

Heard neither – ”

We pause for a moment to consider what a sea-captain might have expected to hear, by night, in the Atlantic ocean – he heard

“ – neither the warbling of the nightingale

Nor melody o’ the Libyan lotusflute,”

but he did hear the three daughters of Hesper singing the following song –

“The golden apple, the golden apple, the hallowèd fruit,

Guard it well, guard it warily,

Singing airily

Standing about the charmèd root,

Round about all is mute”

mute, though they sung so loud as to be heard some leagues out at sea

“ – all is mute

As the snow-field on mountain peaks,

As the sand-field at the mountain foot.

Crocodiles in briny creeks

Sleep, and stir not: all is mute.”

How admirably do these lines describe the peculiarities of this charmed neighbourhood – fields of snow, so talkative when they happen to lie at the foot of the mountain, are quite out of breath when they get to the top, and the sand, so noisy on the summit of a hill, is dumb at its foot. The very crocodiles, too, aremute – not dumb but mute. The “red-combed dragon curl’d” is next introduced

“Look to him, father, lest he wink, and the golden apple be stolen away,

For his ancient heart is drunk with overwatchings night and day

Sing away, sing aloud evermore, in the wind, without stop.”

The north wind, it appears, had by this time awaked again –

“Lest his scaled eyelid drop,

For he is older than the world”

older than the hills, besides not rhyming to “curl’d” would hardly have been a sufficiently venerable phrase for this most harmonious of lyrics. It proceeds,

“If ye sing not, if ye make false measure,

We shall lose eternal pleasure,

Worth eternal want of rest.

Laugh not loudly: watch the treasure

Of the wisdom of the west.

In a corner wisdom whispers.

Five and three

(Let it not be preached abroad) make an awful mystery” – p102

This recipe for keeping a secret, by singing it so loud as to be heard for miles, is almost the only point, in all Mr. Tennyson’s poems, in which we can trace the remotest approach to anything like what other, men have written, but it certainly does remind us of the “chorus of conspirators” in the Rovers.Hanno, however, who understood no language but Punic – (the Hesperides sang, we presume, either in Greek or in English) – appears to have kept on his way without taking any notice of the song, for the poem concludes,

“The apple of gold hangs over the sea,

Five links, a golden chain, are we,

Hesper, the Dragon, and sisters three;

Daughters three,

Bound about

All round about

The gnarlèd bole of the charmèd tree,

The golden apple, the golden apple, the hallowèd fruit.

Guard it well, guard it warily,

Watch it warily,

Singing airily,

Standing about the charmèd root.” – p107

We hardly think that, if Hanno had translated it into Punic, the song would have been more intelligible.The “Lotuseaters” – a kind of classical opium-eaters – are Ulysses and his crew. They land on the “charmèd island” and eat of the “charmèd root” and then they sing

“Long enough the winedark wave our weary bark did carry.

This is lovelier and sweeter

,Men of Ithaca, this is meeter,

In the hollow rosy vale to tarry,

Like a dreamy Lotuseater—a delicious Lotuseater!

We will eat the Lotus, sweet

As the yellow honeycomb;

In the valley some, and some

On the ancient heights divine,

And no more roam,

On the loud hoar foam,To the melancholy home,

At the limits of the brine

The little isle of Ithaca, beneath the day’s decline” – p116

Our readers will, we think, agree that this is admirably characteristic, and that the singers of this song must have made pretty free with the intoxicating fruit. How they got home you must read in Homer: – Mr. Tennyson – himself, we presume, a dreamy lotus-eater, a delicious lotus-eater – leaves them in full song.

Next comes another class of poem – Visions. The first is the “Palace of Art”, or a fine house, in which the poet dreams that he sees a very fine collection of well-known pictures. An ordinary versifier would, no doubt, have followed the old routine, and dully described himself as walking into the Louvre, or Buckingham Palace, and there seeing certain masterpieces of painting: a true poet dreams it. We have not room to hang many of these chefs-d’oeuvre, but for a few we must find space – “The Madonna”

“The maid mother by a crucifix,

In yellow pastures sunny warm,

Beneath branch work of costly sardonyx

Sat smiling – babe in arm” – p72

The use of this latter, apparently, colloquial phrase is a deep stroke of art. The form of expression is always used to express an habitual and characteristic action. A knight is described “lance in rest” – a dragoon,“sword in hand” – so as the idea of the Virgin is inseparably connected with her child, Mr. Tennyson reverently describes her conventional position – “babe in arm”.His gallery of illustrious portraits is thus admirably arranged:—The Madonna – Ganymede – St Cecilia – Europa – Deep-haired Milton – Shakspeare – Grim Dante – Michael Angelo – Luther – Lord Bacon – Cervantes – Calderon – King David – “the Halicarnassëan’” (quwre, which of them ?) – Alfred, (not Alfred Tennyson, though no doubt in any other man’s gallery he would have had a place) and finally –

“Isaiah, with fierce Ezekiel,

Swarth Moses by the Coptic sea,

Plato, Petrarca, Livy, and Raphael,

And eastern Confutzee!’

We can hardly suspect the very original mind of Mr. Tennyson to have harboured any recollections of that celebrated Doric idyll, “he groves of Blarney”, but certainly there is a strong likeness between Mr. Tennyson’s list of pictures and the Blarney collection of statues –

“Statues growing that noble place in,

All heathen goddesses most rare,

Homer, Plutarch, and Nebuchadnezzar,

All standing naked in the open air!”

In this poem we first observed a stroke of art (repeated afterwards) which we think very ingenious. No one who has ever written verse but must have felt the pain of erasing some happy line, some striking stanza, which, however excellent in itself, did not exactly suit the place for which it was destined. How curiously does an author mould and remould the plastic verse in order to fit in the favourite thought ; and when he finds that he cannot introduce it, as Corporal Trim says, any how, with what reluctance does he at last reject the intractable, but still cherished offspring of his brain! Mr. Tennyson manages this delicate matter in a new and better way; he says, with great candour and simplicity, “If this poem were not already too long, I should have addedthe following stanzas,” and then he adds them, (p84) – or, “the following lines are manifestly superfluous, as a part of the text,, but they may be allowed to stand as a separate poem” (p121,) which they do – or, “I intended to have added something on statuary, but I found it very difficult” – (he had, moreover, as we have seen, been anticipated in this line by the Blarney poet) – “but I had finished the statues of Elijah andOlympias – judge whether I have succeeded,” (p78)—and then we have these two statues. This is certainly the most ingenious device that has ever come under our observation, for reconciling the rigour of criticism with the indulgence of parental partiality. It is economical too, and to the reader profitable, as by these means“We lose no drop of the immortal man.”

The other vision is “A Dream of Fair Women”, in which the heroines of all ages – some, indeed, that belong to the times of ”heathen goddesses most rare” – pass before his view. We have not time to notice them all, but the second, whom we take to be Iphigenia, touches the heart with a stroke of nature more powerful than even the veil that the Grecian painter threw over the head of her father.

“ – dimly I could descry

The stern blackbearded kings with wolfish eyes,

Watching to see me die.

The tall masts quivered as they lay afloat;

The temples, and the people, and the shore;

One drew a sharp knife through my tender throat

Slowly, and nothing more!’

What touching simplicity – what pathetic resignation – he cut my throat – “nothing more!” One might indeed ask, “what more she would have?

But we must hasten on; and to tranquillize the reader’s mind after the last affecting scene, shall notice the only two pieces of a lighter strain which the volume affords. The first is elegant and playful; it is a description of the author’s study, which he affectionately calls his Darling Room.

“O darling room, my heart’s delight;

Dear room, the apple of my sight;

With thy two couches, soft and white,

There is no room so exquisite;

No little room so warm and bright,

Wherein to read, wherein to write.”

We entreat our readers to note how, even in this little, trifle, the singular taste and genius of Mr. Tennyson break forth. In such a dear little room a narrow-minded scribbler would have been content with one sofa, and that one he would probably have covered with black mohair, or red cloth, or a good striped chintz; how infinitely more characteristic is white dimity! – ‘tis as it were a type of the purity of the poet’s mind.

He proceeds

“For I the Nonnenwerth have seen,

And Oberwinter’s vineyards green,

Musical Lurlei; and between

The hills to Bingen I have been,

Bingen in Darmstadt, where the Rhene

Curves towards Mentz, a woody scene.

Yet never did there meet my sight,

In any town, to left or right,

A little room so exquisite;

With two such couches soft and white;

Not any room so warm and bright,

Wherein to read, wherein to write – p153

A common poet would have said that he had been in London or in Paris – in the loveliest villa on the banks of the Thames, or the most gorgeous chateau on the Loire – that he had reclined in Madame de Stael’s boudoir, and mused in Mr. Rogers’s comfortable study; but the darling room of the poet of nature (which we must suppose to be endued with sensibility, or he would not have addressed it) would not be flattered with such common-place comparisons – no, no, but it is something to have it, said that there is no such room in the ruins of the Drachenfels, in the vineyard of Oberwinter, or even in the rapids of the Rhene, under the Lurleyberg, We have ourselves visited all these celebrated spots, and can testify) in corroboration of Mr. Tennyson, that we did not see in any of them anything like this little room so exquisite.The second of the lighter pieces, and the last with which we shall delight our readers, is a severe retaliation on the editor of the Edinburgh Magazine, who, it seems, had not treated the first volume of Mr. Tennyson with the same respect that we have, we trust, evinced for the second.

TO CHRISTOPHER NORTH

“You did late review my lays,

Crusty Christopher;

You did mingle blame and praise,

Rusty Christopher.

When I learnt from whom it cameI forgave you all the blame,

Musty Christopher;

I could not forgive the praise,

Fusty Christopher” – p153

Was there ever anything so genteelly turned – so terse – so sharp – and the point so stinging and so true?

“I could not forgive the praise,Fusty Christopher!”

This leads us to observe on a phenomenon which we have frequently seen, but never been able to explain. It has been occasionally our painful lot to excite the displeasure of authors whom we have reviewed, and who have vented their dissatisfaction, some in prose, some in verse, and some in what we could not distinctly say whether it was verse or prose; but we have invariably found that the common formula of retort was that adopted by Mr. Tennyson against his northern critic, namely, that the author would always“…Forgive us all the blame,But could not forgive the praise.”

Now this seems very surprising. It has sometimes, though we regret to say rarely, happened, that, as in the present instance, we have been able to deal out unqualified praise, but we never found that the dose in this case disagreed with the most squeamish stomach; on the contrary, the patient has always seemed exceedingly cornfortable after he had swallowed it. He has been known to take the Review home and keep his wife from a ball, and his children from bed, till he could administer it to them, by reading the article aloud. He has even been heard to recommend the Review to his acquaintance at the clubs, as the best number which has yet appeared, and one, who happened to be an MP as well as an author, gave a conditional order, that in case his last work should be favourably noticed, a dozen copies should be sent down by the mail to the borough of ———. But, on the other hand, when it has happened that the general course of our criticism has been unfavourable, if by accident we happened to introduce the smallest spice of praise, the patient immediately fell into paroxysms – declaring that the part which we foolishly thought might offend him had, on the contrary, given him pleasure – positive pleasure, but that which he could not possibly either forget or forgive, was the grain of praise; be it ever so small, which we had dropped in, and for which, am not for our censure, he felt constrained, in honour and conscience, to visit us with his extreme indignation. Can any reader or writer inform us how it is that praise in the wholesale is so very agreeable to the very same stomach that rejects it with disgust and loathing, when it is scantily administered; and above all, can they tell us why it is, that the indignation and nausea should be in the exact inverse ratio to the quantity of the ingredient?

These effects, of which we could quote several cases much more violent than Mr. Tennyson’s, puzzle us exceedingly; but a learned friend, whom we have consulted, has, though be could not account for the phenomenon, pointed out what he thought an analogous case. It is related of Mr. Alderman Faulkener, of convivial memory, that one night when he expected his guests to sit late and try the strength of his claret and his head, he took the precaution of placing in his wine-glass a strawberry, which his doctor, he said, had recommended to him on account of its cooling qualities: on the faith of this specific, he drank ever more deeply, and, as might be expected, was carried away at an earlier period and in rather a worse state, than was usual with him. When some of his friends condoled with him next day and attributed his misfortune to six bottles of claret which he had imbibed, the Alderman was extremely indignant – “the claret” he said, “was sound, and never could do any man any harm – his discomfiture was altogether caused by that damned single strawberry” which he had kept all night at the bottom of his glass.