Letter to the Editor, 7 February 2024

According to a Mr Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (the Daily Mail, December 30, 2023), western liberal capitalist countries are best because they “produce the most danceable pop songs,” the “biggest blockbuster movies,” and “the best night clubs”; oh, and superlatively free and democratically effectual elections. What most serious analysts of current affairs cannot dispute, however, is the comparative geo-strategic decline of the West, aggravated by economic turmoil, transnational terrorism and trafficking, Chinese and Islamist resurgence, plus an unprecedented sub-Saharan birth-rate. Concerning the latter, according to Steve Jones (writing in The Language of the Genes) “A third of the world’s population may be of African origin by 2050”.

Hitherto dogged by what Correlli Barnet calls “overstretch coupled with underperformance”, our overcrowded island is currently a sitting-duck yet countenances WMD conflict against Russia, China, Iran and North Korea, an “Evil Axis” whose area jointly exceeds 10 million square miles. The political class has allowed British defences to become weak and inefficient, highlighted by the Royal Navy’s recent sea-lane action in a situation nevertheless provocative of regional explosion. Meanwhile, the Chief of the General Staff calls for war-footing “mobilisation” of the “whole nation”. But “Britain’s collapsing birth rate could lose us the next war”, warns Michael Deacon (Daily Telegraph, 27 January 2024). The ONS expects a 6 million population increase by 2036, almost entirely from immigration. Just how many of these polyethnic incomers would willingly join a perilous offensive on behalf of Bibi Netanyahu, Volodymyr Zelensky, or Lai Ching-te?

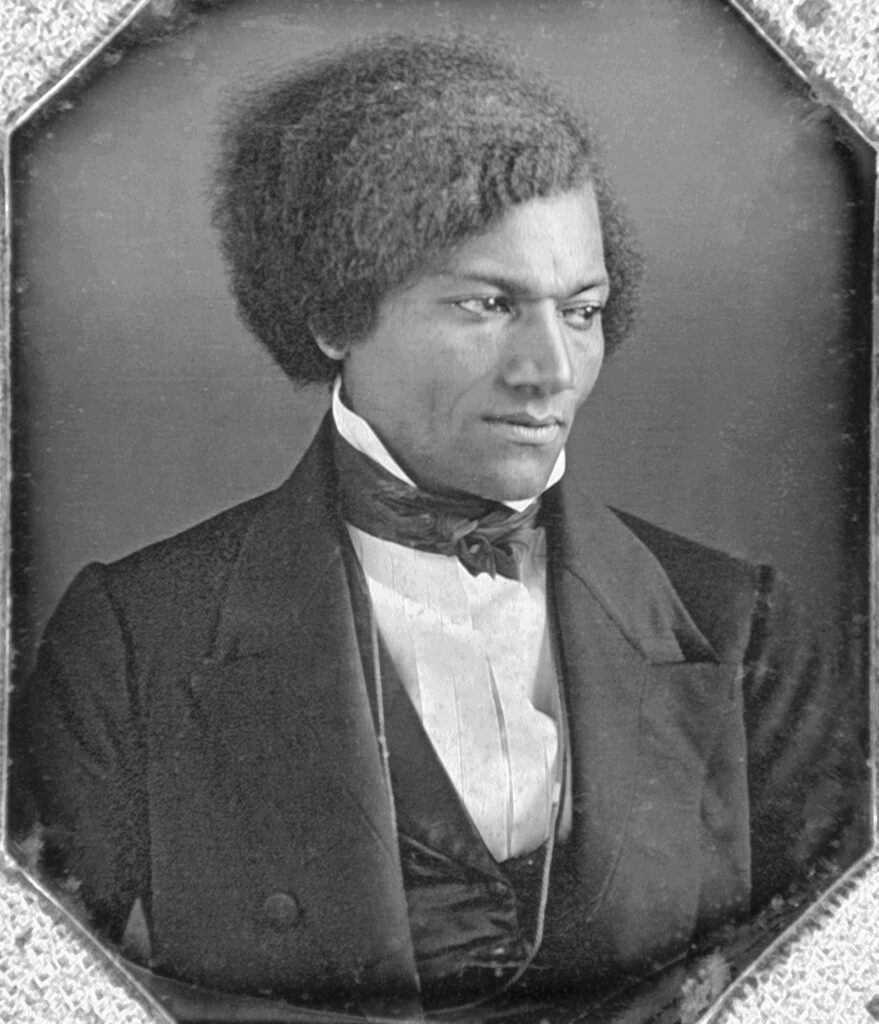

Our military vulnerability is compounded by the insidious combination of internal social decline and a dominant ideology that impedes its reversal. Data on crime and behaviour, health and addiction, education and childcare, transport and communication, banking services, tax-aided charities, council funds, asylum management and landscape conservation, show that the sheer numbers of people requiring cure, care, coaching or control are beginning to overwhelm the available personnel competent adequately to provide the facilities required. Declining national intelligence is doubtless another key factor, for which environmental causes are proposed, although genetics cannot be excluded. Regarded as a primary cause of the decline and collapse of several great empires, differential birth-rates between creative elites and citizens of limited abilities remain a legitimate concern of thoughtful, albeit sometimes execrated, observers.

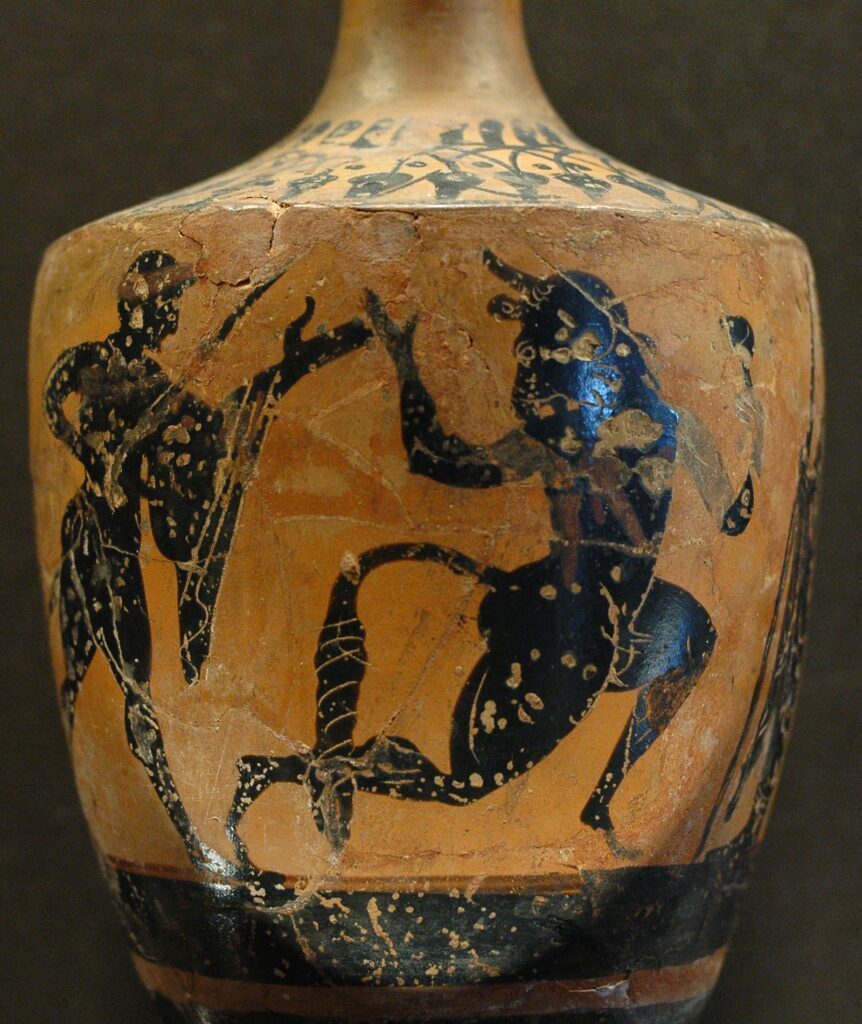

“The burdens of civilised life grow heavier in each generation,” observed W. R. Inge, back in 1927. Science and technology can solve many problems, including some they previously helped to create. But they require enough scientists and engineers for innovation and implementation, and wise leadership. Can we escape the present grip of inertia and incompetence, complacency and corruption, and rescue civilization from woke induced decadence or nuclear annihilation?

From David Ashton