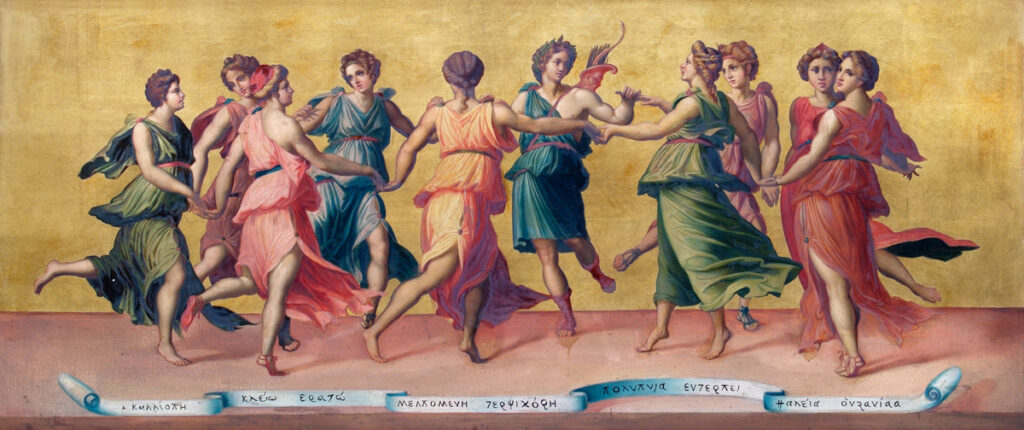

‘Dance of Apollo and the Muses’, Baldassare Peruzzi

Endnotes, November 2022

In this edition: Haydn from Kent: a fanfare from America, reviewed by Stuart Millson

The East Malling Singers, conductor, Ciara Considine, performed Haydn’s Nelson Mass to warm applause last month, in the fine acoustic of their village church, St. James the Great. Accompanied by a an exceptionally fine line-up of soloists – Gillian Ramm (soprano), Rachael Lloyd (mezzo-soprano), Tom Robson (tenor) and Luke Gasper (bass) – the Singers successfully scaled the heights of the work’s imposing opening, the great Kyrie, which rises in martial mood with timpani and brass to the fore.

Cohesion of voices and a ‘tightness’ in the delivery of many of the more ornate sections of the work carried this Nelson Mass along, as if sailing on a strong tide. The emphatic delivery of the opening section seemed to spur the choir to even greater things in Gloria in excelsis deo; a jubilant release from the brooding introduction. Like Mozart, Haydn possessed that seemingly inexhaustible capacity and inspiration to compose masses (and Masses) of music, in practically every form; from oratorio (the magnificent, The Creation, has also been performed here in East Malling) to chamber works, solo piano pieces and concertos.

Born in 1732, Joseph Haydn was a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and for a great part of his musical life was engaged by the powerful Esterhazy family, for which he composed celebratory pieces, such as a mass for the name day of Princess Marie Hermenegild. The latter work was composed in 1798, not long after Haydn had completed The Creation. Yet he registered the work (completed, incidentally, in the record time of just over 50 days) as: Mass in Straitened Times. Let us not forget that the end of the 18th-century/beginning of the 19th, was a period of extreme political turbulence for Europe; the continent dominated by Napoleon, the sea-lanes by the resisting Royal Navy, hence Haydn’s choice of title.

The first performance took place in Eisenstadt, and it was on a visit to that town in 1800 that Admiral Nelson heard the work; his celebrity conferring a new title on the piece: Nelson Mass. At the time, people sought to find echoes of Nelson’s career and achievements in this forty-minute-long piece. Had not Nelson defeated the French at the Battle of Aboukir Bay in the very same year in which Haydn had composed the mass? That was indeed true, but there is no evidence to suggest that Haydn, in his Austro-Hungarian fastness, would have had any idea of the sea-battle taking place between Nelson and Napoleon’s Mediterranean fleet. Here we truly find a work named because of a happy accident: Nelson simply attending a Haydn concert.

For the East Malling Singers, the great tenderness, generosity and often just simple melodies – such as in the Agnus Dei, or even the gently-rolling, optimistic ending – Dona nobis pacem – provided some heart warming highlights to the evening, but it is surely in the opening of the Credo that Haydn gives us an arc of light: a movement of breathtaking baroque majesty, more than competently taken up by this ‘amateur’ band of voices.

Haydn lived to see the defeat of the combined French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar in 1805, but not the final demise of that audacious son of Corsica who became Emperor of France. The composer died in 1809, but became forever enthroned as one of the great classical-era composers; establishing that famous canonical trinity which, after J.S. Bach, set the gold-standard for music: Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven.

In the first half of the concert, the choir performed Bruckner’s motet, Locus iste, and Josef Rheinberger’s Abendlied – both works creating an immediate atmosphere of Middle-Europe: dimly-lit churches in Upper Austria, twilight forests in Bohemia; with the tenor, soprano, mezzo and bass soloists also contributing a medley of operatic arias and English song. Offenbach and Bizet sparkled (accompanied by pianists Nick Bland and John Hayden), but for this observer, the piece that truly stood out was Vaughan Williams’s Vagabond, from Songs of Travel. In bass, Luke Gasper’s hands (and in this, the Vaughan Williams 150th anniversary year), we truly found ourselves on the moonlit, open road through rural shires and candlelit villages.

Finally, in complete contrast, a discovery: the music of contemporary United States composer, Randall Svane – his majestic fanfare (a live recording sent to The QR on an mp3 file) also manages brief moments of introspection, as if we are floating above the Appalachian mountains, just pondering the grandeur of the scene. Spans of brass writing bring a Copland-like horizon into view, and at the end, with Randall Svane unleashing his full force, it as if we were leaving the orbit of the Earth altogether on a NASA mission!

We are looking forward to hearing more from this composer, and it looks as though the Three Choirs Festival here in England have recognised his talents: a new work for orchestra, Quantum Flight, is destined to dazzle them soon, at Gloucester Cathedral.

Stuart Millson is Classical Music Editor of QR

For a refreshing, lucid alternative views from “past” writers, try W. H. Mallock, George Chatterton-Hill, Gustave LeBon and Robert Michels. Lasting wisdom in complete contrast to the slovenly verbiage of the woke clerisy.