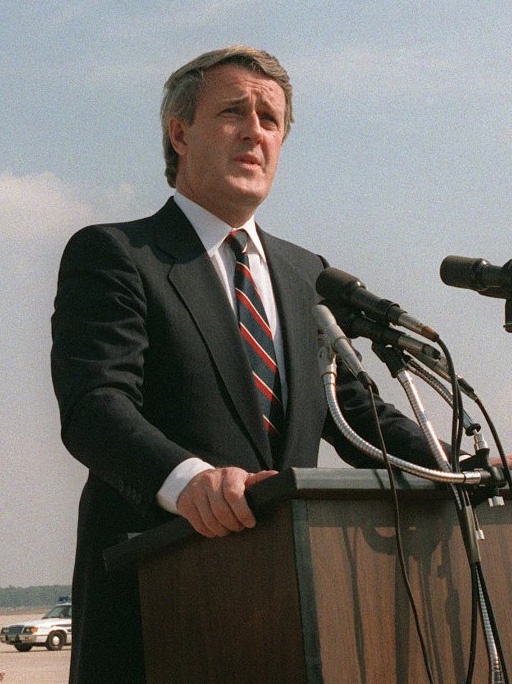

Brian Mulroney, 1984, courtesy Britannica.com

Brian Mulroney and the Failure of Conservatism

Mark Wegierski marks the Sesquicentennial of Canadian Confederation (article 1)

Brian Mulroney was one of the most disappointing Prime Ministers that Canada ever had. As leader of the federal Progressive Conservative party, Mulroney at that time ostensibly represented the main focus of what could be called the “Centre-Right Opposition” in Canada. The use of that term suggests the perennial underdog status of that option in Canadian politics, especially after the federal election of 1963, when Liberal Lester B. Pearson defeated the staunch Tory, John Diefenbaker. As each successive decade rolled by, it could be argued that the social and cultural hold of left-liberalism on the populace has increased exponentially. Although Mulroney was able to win huge majorities in the federal Parliament in 1984 and 1988, he was unable to make any significant changes in this ever-accelerating trajectory. Indeed, one of the consequences of Brian Mulroney’s Prime Ministership may be that winning a Conservative majority in the federal Parliament is nearly impossible, for even the most adept and skilful politician.

During his tenure in Ottawa between 1984 and 1993, it appeared that Brian Mulroney lacked any clear understanding of the context in which he operated, or even of the real nature of power, which he was said to be so avidly seeking. It has long ago become accepted that “the permanent government” of high-ranking civil servants (such as the unelected Deputy Ministers), often wields greater power than almost any elected government. One could compare, for example, the power and influence of a backbench Member of Parliament to that of a middle-level bureaucrat in a politically-sensitive post.

By the 1980s, the rule of the Liberal Party in Canada had been virtually uninterrupted for decades, and in fact had carried on, with only a few Conservative interludes, since 1896. This meant that the federal civil service was filled with Liberal Party and liberal-oriented appointees and supporters, who did their best to undermine the Mulroney government, and its more right-leaning initiatives, from within.

Since Mulroney had in fact won the second-largest majority in Canadian history, it was implicit in his mandate to initiate a general housecleaning and turn-over of staff, certainly in the higher echelons of the civil service. This would be what the media refers to as a “purge”. But this never happened and, in fact, an opposite trend emerged. A former leader of the socialist New Democratic Party, Stephen Lewis, was appointed as Canada’s Ambassador to the UN. NDP MP Ian Deans was given the chairmanship of the Public Service Relations Board, after his early and unexpected retirement from Parliament. Gerry Caplan, one of the NDP’s leading theoreticians, headed up a Task Force investigating the role of the media in Canadian society. Pierre Juneau, once a high-ranking Liberal Party member, and Trudeau associate and appointee, remained at the head of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), and that vital media instrument remained as pro-Liberal (small and big ‘l’) as ever. Other sectors of the administrative apparatus, most notably the Department of External Affairs, remained equally untouched by the change in the elected government.

The Mulroney government’s inability to bring the CBC, the civil service apparatus, and other government agencies and boards under closer control and scrutiny, resulted in an inability to carry out any policies significantly different from the Liberal ones, even if it had the desire to do so. Given the apparent strength of his 211-seat majority, Mulroney was in a position to launch serious initiatives in many directions, to try and challenge the policies of previous Liberal governments. That he did not do so stemmed also from the fact that he himself was viscerally a “small-l liberal”

Had he wanted to take a different course, Mulroney would have had to have found a proper way of “handling” the media. During his two terms, instead of haggling over petty or ungermane issues, Mulroney could have charted a new course for Canada, establishing a new “National Policy”, setting a new agenda, and emerged perhaps as one of Canada’s greatest Prime Ministers, “the saviour of his country”. Mulroney’s combination of a lack of a systematic, principled conservative philosophy, along with his elements of visceral “small l-liberalism”, meant that he failed to understand the nature of the mass media in modern society. The Canadian media of the 1980s did not exist to put on “Brian-and-Mila shows”, but was generally adversarial and obstructionist to the core.

The best course for any serious politician to follow when dealing with the media is to carry out the best policies regardless of media reaction; to appeal to the people over the heads of the media; and to find ways of short-circuiting the media information monopoly. Mulroney should have recognized that the media would be against him from the very beginning and found ways of working around it. His attempts to curry favour with the media were politically unsound and unrealistic. Mulroney should have realized that the media does not represent the general opinions of “the people”, but rather of a handful of newspaper editors and broadcasting heads, who may be as mistaken and fallible as anyone else. He remained unaware (or pretended to remain unaware) of these fundamental political realities.

Faced with such a weak (towards them) opponent, the media lunged in with gusto to wreak maximum havoc upon Mulroney’s government. It is a cardinal law of politics that vacuums of power will always be filled. (According to Marx’s theories, this is the so-called “correlation of forces”.) As the media, or any other social group, presses hard in a direction dictated by its own value-systems, this pressure can be held to reasonable limits only by a strong and significant counter-pressure, generated by the government, or other social groups. When a society remains unresistant to and largely unaware of these strong pressures, these pressures only intensify and grow more acute. Thus a state of “equilibrium” between social forces is quite rare, either one side or the other will strive for victory. But such a victory is usually marked not by the cessation of the struggle, but by the desire to make the triumph as full and complete as possible. Thus, Mulroney, by refusing to realise that many in the media were his real opponents, and trying to curry favour with them, opened up the way for the complete rout of his position, in 1993, if not 1988.

In fact, Brian Mulroney’s policies were virtually indistinguishable from those of the Liberals, and most of his government’s “crises” were over personal, rather than serious policy issues. It is one thing to drop to 23% popularity because of the bold, new, unpopular initiatives one has taken, but quite another to do so on the basis of petty graft and a “do-nothing” policy. There is often nothing better than stating one’s position strongly, and sticking to one’s guns, as Ronald Reagan’s two-term triumph has shown. He proved to be one of the most successful democratic politicians of the Twentieth Century.

According to a poll taken in July 1987 about possible voting preferences in a federal election, the NDP had the support of 41% of decided voters; the Liberals, 35%; and the PCs, 23%. (31% of voters declared themselves undecided.) It was obviously because of the media (in particular, the CBC), that the puny formal Opposition of 40 Liberal and 30 NDP MPs, were able to present such a continuous and effective challenge to a numerically overwhelming majority government.

Given the enormous power of the media (“one thousand repetitions make one truth”), and Mulroney’s lack of real political apprehension, and of a real ethos with which to arm and defend himself, his government was clearly doomed.

Mulroney also did not realize (or preferred to ignore) the extent to which the power of the government is today used to extract tax-money from the social mainstream, and direct it to the causes, groups, and programs of the social peripheries. Every dollar he gave to such individuals and groups was a dollar given to his ideological enemies, who were exerting maximum efforts to sweep him from power, and utterly defeat the PC party in general, and “small-c conservatism” in particular.

For all his supposed “Machiavellianism”, it could be argued that Mulroney misunderstood what “power” really is. Power is not an inert thing, an end in itself, but rather a means to other ends. Power is the ability to effect the social and physical environment — to strengthen, or introduce changes to, people’s behaviour-patterns and attitudes — using a wide range of coercive, utilitarian, and normative instrumentalities. Presumably, those effects one wishes to introduce are those in accord with one’s own value-systems and beliefs.

Mulroney had no clear and coherent value-system, apart from the belief in pure self-aggrandizement and “power-in-itself”, as well as a left-liberal sentiment and instinct more appropriate to the Liberals and NDP. (As on the capital punishment issue where, according to polls, over 80% of Canadians were at that time in favour of the death penalty. It is an open secret that Mulroney arm-twisted his Quebec MPs and generally did his best to undermine the parliamentary vote taken at that time, in regard to restoring capital punishment.)

Mulroney manifestly lacked what the neoconservative commentator William Kristol called the ability to “govern strategically”, something which Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau did so successfully for so long. To “govern strategically” means to have a set of certain fundamental policy objectives (i.e., what is commonly called an “agenda”), which springs from one’s personal philosophical framework, and to clearly enunciate it and fight for it in the political arena. Those who do not “govern strategically” find themselves perpetually on the defensive, reacting to developments shaped by others, fighting on other’s terrain, at someone else’s chosen time and place, and being judged by other’s criteria. Without a fundamental intellectual framework or overarching “vision”, Brian Mulroney was condemned to failure. Although successful in gaining formal power, he was incapable of exercising it de facto. His two terms ended in disaster.

The two most memorable accomplishments of Mulroney were the Canada-U.S. Free Trade deal (something that had long been opposed by the Conservative Party – and supported by the Liberal Party), and the Goods & Services Tax (GST), Canada’s version of a value-added tax, which largely helped only the Liberals after 1993 in allowing them to have huge government spending and balance the budget at the same time. The two major attempts to conciliate Quebec, the Meech Lake Accord, and the Charlottetown Agreements, both failed.

To use the terminology of Vilfredo Pareto, Mulroney could be seen as a super-cunning “fox”, who lacked the backbone and principles of a “lion”, and so was unable to effectively exercise his power, however successful he was in attaining it in the purely formal sense.

The failure of Brian Mulroney in the 1980s reflected the general failure of the federal Progressive Conservative party in enunciating a clear and consistent philosophy and set of policies, a signal failure to take advantage of one of their rare and fleeting moments of electoral triumph. Saddled with the leadership of Brian Mulroney, the domination of key ministerial portfolios by the “Clark clique”, and the ever-present shadow of Dalton Camp and Associates (who had “knifed” John Diefenbaker and carefully “guided” the party through twenty years of Liberal hegemony), the federal PC party was headed for the disaster of 1993, while apparently ignorant of the social forces working to bring it down. PC party members proved incapable of turning around the direction of the party even for purely personal, selfish reasons. The PC party appeared incapable of acting even in its narrowly-conceived self-interest, let alone for the sake of higher principles.

Purely from the standpoint of pragmatic politics, the embracing by the federal PCs of Liberal and NDP positions, policies, and programs, was a path to political suicide. While alienating and confusing core PC supporters (who indeed turned in large numbers to Preston Manning’s Reform Party), these policies failed to win over convinced liberals and socialists. Given the choice between PCs enacting liberal policies and Liberals enacting liberal policies, whom were the more liberal-oriented sections of the electorate more likely to choose? This argument against the PCs adopting liberal policies is also instructive in terms of the situations in Ontario and New Brunswick provincial politics in the 1980s. Indeed, the PCs were solidly trounced in both provinces in the latter half of the 1980s.

Mulroney was not handed the second-largest majority in Canadian history to continue and extend the policies of previous Liberal governments. His adoption of Liberal and NDP policies and programs could be seen as a frustration of the democratic process, which presupposes that the voters have the right to choose from a variety of widely-differing platforms and philosophies, to make at least some fundamental choices. As Mulroney drew ever closer to Liberal and NDP policies and programs, he weakened not only the future electoral prospects of the federal PCs, he also made a mockery of that trust which people put in him.

By “governing strategically” with his 211-seat majority, Mulroney, even in four years, could have dramatically changed the shape and direction of all of Canadian society, as Trudeau had done during his sixteen years in power. As society changed in response to his initiatives, Mulroney would have found that his social base and support would have grown, rather than shrunk. Rather than a helpless pawn of other tendencies and powers, Mulroney would have himself become the chief focus of power in Canadian society, as befits a democratically-elected Prime Minister. Rather than presiding over yet another brief Conservative party interval, Mulroney might well have found himself leading Canada proudly to the Twenty-First Century, as the head of an effective and dynamic Tory party.

Canada has today reached the most extreme forms of “political correctness” and of the ideological hegemony of “the managerial-therapeutic regime”. It is possible that only the vast, resource-based wealth of Canada allows the country to avoid dystopic and violent outcomes. The weakness and incoherence of the “Centre-Right Opposition”, especially in the 1980s, has certainly contributed to this impasse.

Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and researcher

Like this:

Like Loading...

Brian Mulroney and the Failure of Conservatism

Brian Mulroney, 1984, courtesy Britannica.com

Brian Mulroney and the Failure of Conservatism

Mark Wegierski marks the Sesquicentennial of Canadian Confederation (article 1)

Brian Mulroney was one of the most disappointing Prime Ministers that Canada ever had. As leader of the federal Progressive Conservative party, Mulroney at that time ostensibly represented the main focus of what could be called the “Centre-Right Opposition” in Canada. The use of that term suggests the perennial underdog status of that option in Canadian politics, especially after the federal election of 1963, when Liberal Lester B. Pearson defeated the staunch Tory, John Diefenbaker. As each successive decade rolled by, it could be argued that the social and cultural hold of left-liberalism on the populace has increased exponentially. Although Mulroney was able to win huge majorities in the federal Parliament in 1984 and 1988, he was unable to make any significant changes in this ever-accelerating trajectory. Indeed, one of the consequences of Brian Mulroney’s Prime Ministership may be that winning a Conservative majority in the federal Parliament is nearly impossible, for even the most adept and skilful politician.

During his tenure in Ottawa between 1984 and 1993, it appeared that Brian Mulroney lacked any clear understanding of the context in which he operated, or even of the real nature of power, which he was said to be so avidly seeking. It has long ago become accepted that “the permanent government” of high-ranking civil servants (such as the unelected Deputy Ministers), often wields greater power than almost any elected government. One could compare, for example, the power and influence of a backbench Member of Parliament to that of a middle-level bureaucrat in a politically-sensitive post.

By the 1980s, the rule of the Liberal Party in Canada had been virtually uninterrupted for decades, and in fact had carried on, with only a few Conservative interludes, since 1896. This meant that the federal civil service was filled with Liberal Party and liberal-oriented appointees and supporters, who did their best to undermine the Mulroney government, and its more right-leaning initiatives, from within.

Since Mulroney had in fact won the second-largest majority in Canadian history, it was implicit in his mandate to initiate a general housecleaning and turn-over of staff, certainly in the higher echelons of the civil service. This would be what the media refers to as a “purge”. But this never happened and, in fact, an opposite trend emerged. A former leader of the socialist New Democratic Party, Stephen Lewis, was appointed as Canada’s Ambassador to the UN. NDP MP Ian Deans was given the chairmanship of the Public Service Relations Board, after his early and unexpected retirement from Parliament. Gerry Caplan, one of the NDP’s leading theoreticians, headed up a Task Force investigating the role of the media in Canadian society. Pierre Juneau, once a high-ranking Liberal Party member, and Trudeau associate and appointee, remained at the head of the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), and that vital media instrument remained as pro-Liberal (small and big ‘l’) as ever. Other sectors of the administrative apparatus, most notably the Department of External Affairs, remained equally untouched by the change in the elected government.

The Mulroney government’s inability to bring the CBC, the civil service apparatus, and other government agencies and boards under closer control and scrutiny, resulted in an inability to carry out any policies significantly different from the Liberal ones, even if it had the desire to do so. Given the apparent strength of his 211-seat majority, Mulroney was in a position to launch serious initiatives in many directions, to try and challenge the policies of previous Liberal governments. That he did not do so stemmed also from the fact that he himself was viscerally a “small-l liberal”

Had he wanted to take a different course, Mulroney would have had to have found a proper way of “handling” the media. During his two terms, instead of haggling over petty or ungermane issues, Mulroney could have charted a new course for Canada, establishing a new “National Policy”, setting a new agenda, and emerged perhaps as one of Canada’s greatest Prime Ministers, “the saviour of his country”. Mulroney’s combination of a lack of a systematic, principled conservative philosophy, along with his elements of visceral “small l-liberalism”, meant that he failed to understand the nature of the mass media in modern society. The Canadian media of the 1980s did not exist to put on “Brian-and-Mila shows”, but was generally adversarial and obstructionist to the core.

The best course for any serious politician to follow when dealing with the media is to carry out the best policies regardless of media reaction; to appeal to the people over the heads of the media; and to find ways of short-circuiting the media information monopoly. Mulroney should have recognized that the media would be against him from the very beginning and found ways of working around it. His attempts to curry favour with the media were politically unsound and unrealistic. Mulroney should have realized that the media does not represent the general opinions of “the people”, but rather of a handful of newspaper editors and broadcasting heads, who may be as mistaken and fallible as anyone else. He remained unaware (or pretended to remain unaware) of these fundamental political realities.

Faced with such a weak (towards them) opponent, the media lunged in with gusto to wreak maximum havoc upon Mulroney’s government. It is a cardinal law of politics that vacuums of power will always be filled. (According to Marx’s theories, this is the so-called “correlation of forces”.) As the media, or any other social group, presses hard in a direction dictated by its own value-systems, this pressure can be held to reasonable limits only by a strong and significant counter-pressure, generated by the government, or other social groups. When a society remains unresistant to and largely unaware of these strong pressures, these pressures only intensify and grow more acute. Thus a state of “equilibrium” between social forces is quite rare, either one side or the other will strive for victory. But such a victory is usually marked not by the cessation of the struggle, but by the desire to make the triumph as full and complete as possible. Thus, Mulroney, by refusing to realise that many in the media were his real opponents, and trying to curry favour with them, opened up the way for the complete rout of his position, in 1993, if not 1988.

In fact, Brian Mulroney’s policies were virtually indistinguishable from those of the Liberals, and most of his government’s “crises” were over personal, rather than serious policy issues. It is one thing to drop to 23% popularity because of the bold, new, unpopular initiatives one has taken, but quite another to do so on the basis of petty graft and a “do-nothing” policy. There is often nothing better than stating one’s position strongly, and sticking to one’s guns, as Ronald Reagan’s two-term triumph has shown. He proved to be one of the most successful democratic politicians of the Twentieth Century.

According to a poll taken in July 1987 about possible voting preferences in a federal election, the NDP had the support of 41% of decided voters; the Liberals, 35%; and the PCs, 23%. (31% of voters declared themselves undecided.) It was obviously because of the media (in particular, the CBC), that the puny formal Opposition of 40 Liberal and 30 NDP MPs, were able to present such a continuous and effective challenge to a numerically overwhelming majority government.

Given the enormous power of the media (“one thousand repetitions make one truth”), and Mulroney’s lack of real political apprehension, and of a real ethos with which to arm and defend himself, his government was clearly doomed.

Mulroney also did not realize (or preferred to ignore) the extent to which the power of the government is today used to extract tax-money from the social mainstream, and direct it to the causes, groups, and programs of the social peripheries. Every dollar he gave to such individuals and groups was a dollar given to his ideological enemies, who were exerting maximum efforts to sweep him from power, and utterly defeat the PC party in general, and “small-c conservatism” in particular.

For all his supposed “Machiavellianism”, it could be argued that Mulroney misunderstood what “power” really is. Power is not an inert thing, an end in itself, but rather a means to other ends. Power is the ability to effect the social and physical environment — to strengthen, or introduce changes to, people’s behaviour-patterns and attitudes — using a wide range of coercive, utilitarian, and normative instrumentalities. Presumably, those effects one wishes to introduce are those in accord with one’s own value-systems and beliefs.

Mulroney had no clear and coherent value-system, apart from the belief in pure self-aggrandizement and “power-in-itself”, as well as a left-liberal sentiment and instinct more appropriate to the Liberals and NDP. (As on the capital punishment issue where, according to polls, over 80% of Canadians were at that time in favour of the death penalty. It is an open secret that Mulroney arm-twisted his Quebec MPs and generally did his best to undermine the parliamentary vote taken at that time, in regard to restoring capital punishment.)

Mulroney manifestly lacked what the neoconservative commentator William Kristol called the ability to “govern strategically”, something which Liberal Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau did so successfully for so long. To “govern strategically” means to have a set of certain fundamental policy objectives (i.e., what is commonly called an “agenda”), which springs from one’s personal philosophical framework, and to clearly enunciate it and fight for it in the political arena. Those who do not “govern strategically” find themselves perpetually on the defensive, reacting to developments shaped by others, fighting on other’s terrain, at someone else’s chosen time and place, and being judged by other’s criteria. Without a fundamental intellectual framework or overarching “vision”, Brian Mulroney was condemned to failure. Although successful in gaining formal power, he was incapable of exercising it de facto. His two terms ended in disaster.

The two most memorable accomplishments of Mulroney were the Canada-U.S. Free Trade deal (something that had long been opposed by the Conservative Party – and supported by the Liberal Party), and the Goods & Services Tax (GST), Canada’s version of a value-added tax, which largely helped only the Liberals after 1993 in allowing them to have huge government spending and balance the budget at the same time. The two major attempts to conciliate Quebec, the Meech Lake Accord, and the Charlottetown Agreements, both failed.

To use the terminology of Vilfredo Pareto, Mulroney could be seen as a super-cunning “fox”, who lacked the backbone and principles of a “lion”, and so was unable to effectively exercise his power, however successful he was in attaining it in the purely formal sense.

The failure of Brian Mulroney in the 1980s reflected the general failure of the federal Progressive Conservative party in enunciating a clear and consistent philosophy and set of policies, a signal failure to take advantage of one of their rare and fleeting moments of electoral triumph. Saddled with the leadership of Brian Mulroney, the domination of key ministerial portfolios by the “Clark clique”, and the ever-present shadow of Dalton Camp and Associates (who had “knifed” John Diefenbaker and carefully “guided” the party through twenty years of Liberal hegemony), the federal PC party was headed for the disaster of 1993, while apparently ignorant of the social forces working to bring it down. PC party members proved incapable of turning around the direction of the party even for purely personal, selfish reasons. The PC party appeared incapable of acting even in its narrowly-conceived self-interest, let alone for the sake of higher principles.

Purely from the standpoint of pragmatic politics, the embracing by the federal PCs of Liberal and NDP positions, policies, and programs, was a path to political suicide. While alienating and confusing core PC supporters (who indeed turned in large numbers to Preston Manning’s Reform Party), these policies failed to win over convinced liberals and socialists. Given the choice between PCs enacting liberal policies and Liberals enacting liberal policies, whom were the more liberal-oriented sections of the electorate more likely to choose? This argument against the PCs adopting liberal policies is also instructive in terms of the situations in Ontario and New Brunswick provincial politics in the 1980s. Indeed, the PCs were solidly trounced in both provinces in the latter half of the 1980s.

Mulroney was not handed the second-largest majority in Canadian history to continue and extend the policies of previous Liberal governments. His adoption of Liberal and NDP policies and programs could be seen as a frustration of the democratic process, which presupposes that the voters have the right to choose from a variety of widely-differing platforms and philosophies, to make at least some fundamental choices. As Mulroney drew ever closer to Liberal and NDP policies and programs, he weakened not only the future electoral prospects of the federal PCs, he also made a mockery of that trust which people put in him.

By “governing strategically” with his 211-seat majority, Mulroney, even in four years, could have dramatically changed the shape and direction of all of Canadian society, as Trudeau had done during his sixteen years in power. As society changed in response to his initiatives, Mulroney would have found that his social base and support would have grown, rather than shrunk. Rather than a helpless pawn of other tendencies and powers, Mulroney would have himself become the chief focus of power in Canadian society, as befits a democratically-elected Prime Minister. Rather than presiding over yet another brief Conservative party interval, Mulroney might well have found himself leading Canada proudly to the Twenty-First Century, as the head of an effective and dynamic Tory party.

Canada has today reached the most extreme forms of “political correctness” and of the ideological hegemony of “the managerial-therapeutic regime”. It is possible that only the vast, resource-based wealth of Canada allows the country to avoid dystopic and violent outcomes. The weakness and incoherence of the “Centre-Right Opposition”, especially in the 1980s, has certainly contributed to this impasse.

Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and researcher

Share this:

Like this: