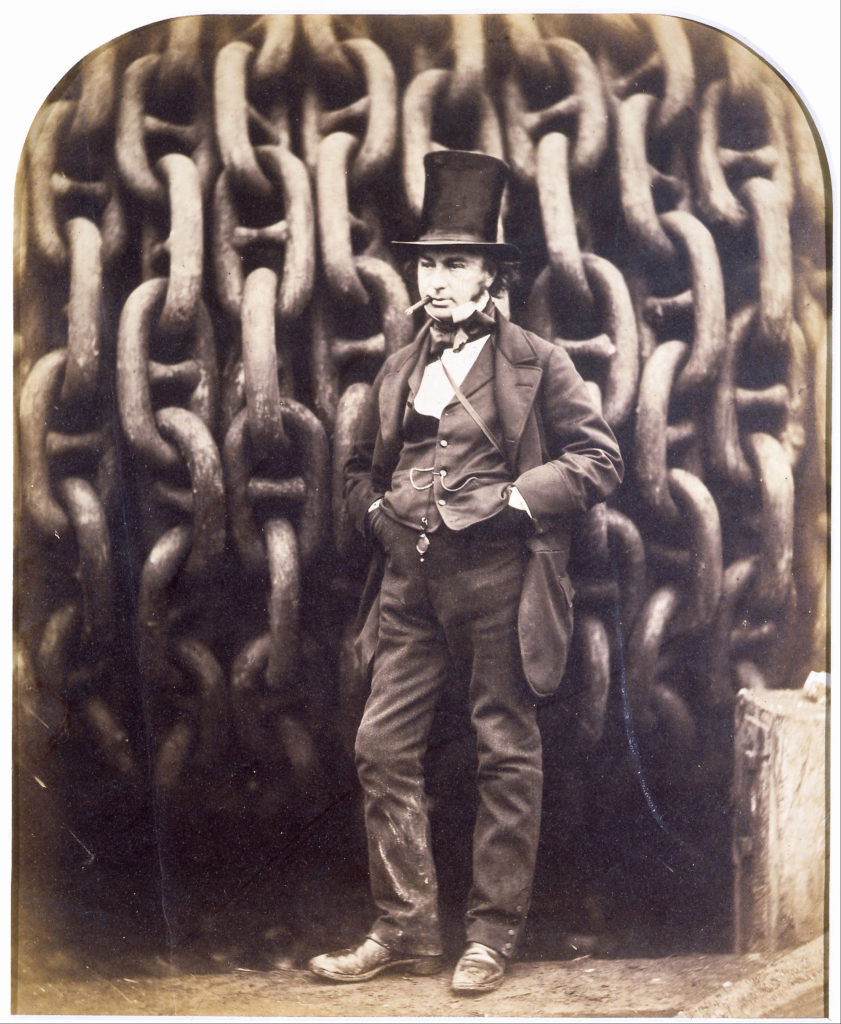

Isambard Kingdom Brunel and the launching chains of the Great Eastern

Victoriana – a Cornucopia

ANGELA ELLIS-JONES reviews a weighty tome

The Victorian World, ed. Martin Hewitt, Routledge, London 2013, Pb., Reprint edition, ISBN 978-0-415-71298-9, 756pp, £44.99

This is the latest volume in a series of which sixteen other volumes have already appeared on topics such as The Greek World, The Roman World and the Islamic World. Over the course of 40 chapters, mostly of a very high standard, the book ‘brings together scholars from history, literary studies, art history, historical geography, historical sociology, criminology, economics and the history of law, to explore themes central to an understanding of the nature of Victorian society and culture, both in Britain and in the rest of the world’. ‘Victorian’ is interpreted to include the 1900s. Each chapter comes with an extensive bibliography; the hundreds of works referenced will keep the enthusiast for Victoriana going for years. Most of the chapters contain at least one black-and-white illustration of something discussed in the text.

The chapters are prefaced by a long introductory chapter by the editor, who persuasively argues that, instead of the usual division of the period 1837-1901 into early, mid- and late Victorian, ‘moments of heightened crisis and adjustment around 1848-51, 1867-70 and 1884-6 created ‘four coherent phases of the Victorian.’’

Perhaps the best way I can convey the range of this work is to note some of the interesting facts it contains. It was only in 1880 that an Act of Parliament was passed to standardise time in Britain, although in practice it had happened much earlier, largely due to the railways (p 13). In the period 1853-94 almost eight million people left Britain and Ireland for destinations outside Europe, but almost 40% of English emigrants (who formed 52% of the total) returned home between 1860 and 1914 (p 147). By 1914 half of all securities listed on the London Stock Exchange were foreign, and over half of the international trade financed by the City had no connection with Britain (p 203). The nineteenth century saw the development of a global reading community that consumed literature across national boundaries (p 555). The world’s biggest art exhibition ‘ever seen’, ‘The Exhibition of the Art Treasures of the United Kingdom’ was held in Manchester from 5 May to 17 October 1857. In a purpose-built hall covering nearly 3 acres, 16,000 items were exhibited, visited by 1.3m people from Britain and abroad (pp 590-1). In 1891, ten percent of pupils at Stonyhurst were from abroad, most from Latin America.

Chapter 39 tells the fascinating story of the Mexican Escandon y Barron brothers who, after education at Stonyhurst, retained a lifelong close connection with Britain. ‘The darlings of society on both sides of the Atlantic’, the Escandons were important players in Britain’s ‘informal’ empire, which embraced many countries beyond the quarter of the world’s peoples who were Victoria’s subjects.

Despite the book’s comprehensive scope, there are some unexpected errors and omissions, both as regards important subject-matter which deserves a chapter, and as regards important facts omitted from chapters. Britain’s pre-eminent nineteenth century historian, Sir David Cannadine, is surprisingly absent; he would undoubtedly have had further interesting things to say about the aristocracy and landed society, which are barely covered at all. Architecture, Music and Philosophy also surely deserve chapters. A chapter on ‘The Victorian Cult of Death’, covering spiritualism too would have been interesting; omission of any mention of that quintessentially Victorian organisation the Society for Psychical Research is a major faux pas. The chapter ‘Worlds of Victorian Religion’ contains very little on Roman Catholicism. The chapter on ‘Private law’ and the laissez-faire state’ by Michael Lobban, Professor of Legal History at Queen Mary, University of London, contains a section on contract law, but inexplicably omits any reference to Patrick Atiyah’s magisterial The Rise and Fall of Freedom of Contract (1979). The chapter on ‘Victorianism at the frontier’ on the white settler colonies, which discourses on their constitutional position, contains no reference to the Colonial Laws Validity Act 1865, which set out the extent of their legislative autonomy from Britain.

As for errors, the editor unfortunately refers to ‘the Congress of Berlin of 1876’ (p 30) – it was 1878.The National Physical Laboratory is incorrectly referred to as the National Physics Laboratory (p 44). The name of William Le Queux is misprinted as Le Quex (p 39); there are a few other misprints throughout the book.

Despite these errors and omissions, this is an immensely impressive work, essential for anyone who is fascinated by Britain at the zenith of her power and prestige. It is the sort of book that should be piled up on tables at Waterstones. Unfortunately its price precludes this. Nevertheless, in terms of what you get for the money, it is excellent value. Perhaps the best compliment that one can pay to it is that it is a tome with several Victorian characteristics: it is full of interesting information and it will improve the mind of anyone who reads it.

ANGELA ELLIS-JONES is a writer and researcher