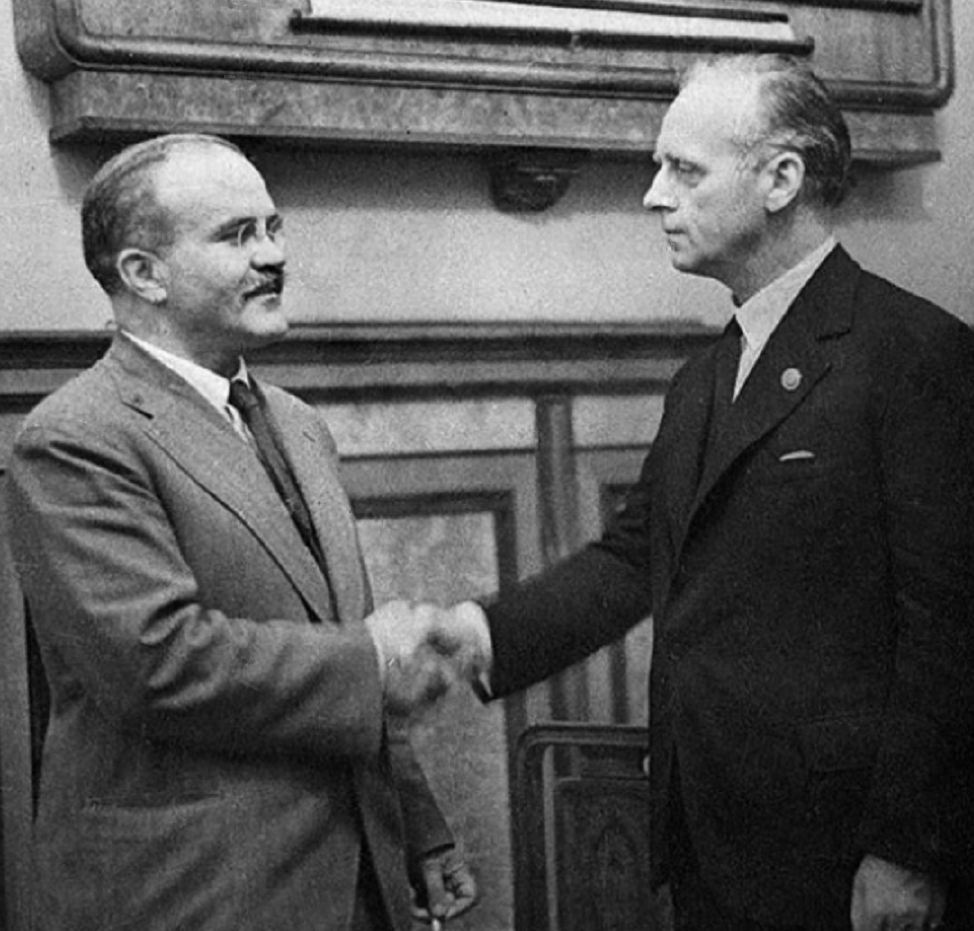

General Heinz Guderian & Brigadier Semyon Krivoshein, Sept 1939, credit Wikipedia

The Devil Spares Pravda

The Devils’ Alliance; Hitler’s Pact with Stalin, 1939-1941, Roger Moorhouse, Basic books, New York, 2014, hb, 382pp, $29.99 US, reviewed by Leslie Jones

As Roger Moorhouse observes in this compelling account, the Nazi-Soviet Non-aggression Pact of August 1939 was “one of the salient events of World War II”. It isolated Poland and thereby led directly to war. In line with the secret protocol of the treaty, Poland was then divided up by “its two malevolent neighbours”. The Soviet annexation of the Baltic states and of the Romanian province of Bessarabia was another direct result of the treaty. Hitler’s occupation of Western Poland subjected the Poles and the Jews to “a horrific regime of exploitation and persecution”. In the aforementioned territories annexed by the USSR, likewise, “class enemies” were killed, persecuted or deported. As the author remarks, Hitler ethnically cleansed Western Poland while the eastern portion was politically cleansed by the Soviets.

Some commentators considered the USSR a “worker’s paradise”, which Stalin was only trying to protect. By means of the pact, they maintained, Stalin enlisted Nazi aggression to accelerate the eventual fall of capitalism. Hitler had been turned West and become an “unwitting tool of the Soviets”. Beatrice Webb, initially appalled, took comfort from the prospect of the Western capitalist democracies being destroyed. Stalin’s policy was “a miracle of successful statesmanship”, she averred. The distinguished future Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, then a Cambridge graduate, had “no reservations” about the new party line. “Stalin never errs”, according to some Communists and fellow travellers. Douglas Hyde, a member of the Communist Party of Great Britain, thought that to protect communism, Stalin should, if necessary, “make an alliance with the devil himself”. But Professor Moorhouse dismisses the notion that Stalin’s motive for engineering the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact was to buy precious time to prepare for an inevitable war with Nazi Germany. He notes that Kingsley Amis, editor of the New Statesman, suspected that the pact’s twin signatories shared something sinister in their DNA. In Le passé d’une illusion; essai sur l’idée communiste au XXe siècle (1995), François Furet subsequently explored this persuasive idea in depth.

The naïve notion that the Nazis were uniquely evil bespeaks a woeful ignorance of this era, according to the author. After the German invasion of Soviet Russia in 1941, Winston Churchill, for one, downplayed his anti-Bolshevism. If Hitler invaded hell, he quipped, he would make a favourable reference to the devil. Germany, for the time being, could no longer invade Britain. Keep the Russians fighting was therefore the order of the day, notwithstanding the disturbing disappearance of thousands of Polish officers in Soviet occupied Poland.

When Brest Litovsk was amicably ceded to the Soviets in September 1939, Heinz Guderian was the local German commander. His Soviet opposite number was Brigadier General Semyon Krivoshein. During “an earlier blossoming of German-Soviet collaboration” in the 1920’s, they had worked together at the Kama tank school in Kazan. Ideology apart, there was a longstanding perception that the USSR and Germany were perfect economic and military partners. This perspective was assiduously promoted by “Easterners” in the German Foreign Office. The Soviets needed technology and precision tools etc and the Germans required raw materials, with which to withstand another possible wartime blockade. Between 1939 and 1941, accordingly, the Nazis and the Soviets “traded secrets, blueprints and raw materials”.

The author always has an eye for the telling detail. He tells us that Heinrich Hoffmann, who photographed the ceremonial signing of the pact, was known as the “Reich Drunkard”; that on Hoffmann’s return to Berlin, Hitler asked him whether Stalin’s earlobes were “ingrown and Jewish, or separate and Aryan”; that Hitler instructed Hoffmann to doctor his photographs, which originally showed Stalin chain smoking; and that Stalin told Ribbentrop that Beria “is our Himmler, [adding that] he’s also very good”.

“Propaganda, all is phony”. According to Machiavelli, “politics is a morally neutral activity concerned with manipulating power…”. There is no ethical or divine order that indicates the ideal state or the highest good for man (quotation from Conflict, War and Revolution, 2022, by Professor Paul Kelly). Viewed from this perspective, British support for Russia, after the German invasion of the USSR in June 1941 (like the by then defunct Nazi-Soviet pact) was “an exercise in realpolitik, a strategic necessity, an uneasy marriage of convenience” (Moorhouse).

Molotov & Ribbentrop, credit Wikipedia

Dr Leslie Jones is Editor of Quarterly Review

A few thoughts:

1. The German claim to Danzig and a corridor through Poland was not in itself unreasonable, but Hitler’s ideology and behaviour were not.

2. During the Russo-German Pact, the Soviets discreetly undermined the British defence preparations while their ideologists in Britain attacked the “upper class” for trade with fascist countries; Ivor Montagu was a key figure in both.

3. Russia annexed a marginally larger area of Poland than Germany, and after WW2 took over large sections of both Poland and Germany.

4. Many Jews in Poland were deported into the Soviet interior, some of their emaciated children exchanged for wartime supplies from Britain at the Iranian border.

5. Relative death-tolls 1939-45 are still matters of conjecture and disagreement.

6. Soviet policy was not technically “racist” but ethnic cleansing in the USSR took place during the decade 1937-1947; see the studies by Otto Pohl, Norman Naimark, Arkadi Vaksberg, &c.

7. Nazi concentration camps were used by communists to intern opponents (not all Nazis) after WW2.

8. Millions of German civilians died during the war and especially the postwar eastward expulsions, often with atrocities.