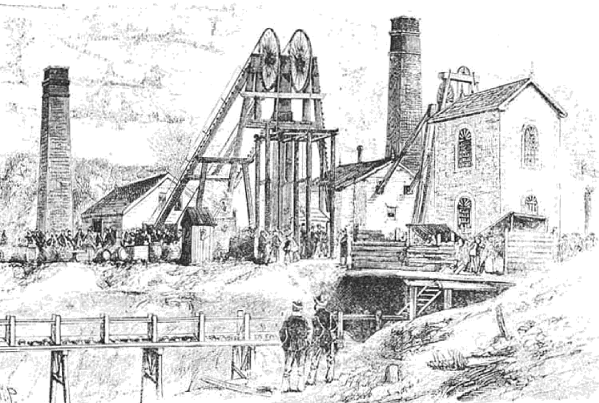

Pendleton Colliery, Illustrated London News 1877

The Colliery Guardian

Bill Hartley mines a copious archive

The Colliery Guardian was founded in 1858 and closed in 1994. By then, it had shrunk to a rather thin monthly publication in a magazine format. Its reduction in size reflected the decline of the British coal industry following the miners’ strike. As the name implies though, the Guardian was once a newspaper and during the 19th century it appeared weekly, reflecting in its pages the size, importance and confidence of the coal industry and the closely allied iron trades, both at home and overseas. Copies of each year’s editions may be found in large heavyweight volumes bound (more like armoured) in leather to contain the many pages of this former broadsheet publication.

The papers’ correspondents home and abroad reported the triumphs and disasters of the coal industry, together with details of new inventions and innovations. British engineers were everywhere in those days and reports flowed in from across the Atlantic, remote corners of the Russian Empire, India and Australia: any part of the globe where coal was mined or might be was covered. This was a world of heavy engineering and every edition of the Guardian was filled with advertisements. Britain truly was workshop of the world. Many towns had an iron foundry and anyone wishing to equip a colliery railway could order locomotives and a fleet of wagons from half a dozen sources to be found in the paper. Other ephemera connected with coal mining covered everything from wheelbarrows to winding machinery. That said, the Guardian was no mere trade paper. If an editorial policy existed then it might have been, ‘anything of interest to our readers’. A dip into its pages at any point throughout the nineteenth century unearths a huge range of news and information; a treasure trove of Victoriana.

The century was littered with industrial disputes in the coal industry; strikes and lockouts sometimes affecting individual collieries, occasionally whole districts. There was no National Union of Mineworkers back then, hence disputes tended to be local and generally involved a scrap with a colliery company or coal owner’s association. Interestingly, the Guardian always steered an impartial course between workers and colliery owners. The paper scrupulously set out the claims of both parties without ever taking sides. Where it did show bias was in an area that much exercised the coal industry during the 1870s. The Truck System was a particularly pernicious arrangement whereby the employer paid workers in tokens or whatever, which could be redeemed only at the company shop where of course the owner’s valuation was placed on the goods. The Truck System had its origins as far back as the 15th century and was only finally eradicated from all areas of working life via a series of Acts of Parliament, the last one as recently as the 1940s. Through the 1870s, the Guardian devoted a great deal of column space to reporting on this abuse and the views of those affected. Several editorials urged the Home Secretary to act which eventually he did. Even so the paper carried many reports of continuing abuses.

The Truck System was a domestic matter with a particular focus on the coal industry but when it came to comment the paper was prepared to go further afield. In a long editorial of July 1870 (they were always long) the paper considered what it termed the ‘Spanish Question’. This was the issue of the Spanish succession which was to prompt the Franco-Prussian war. Since Britain wasn’t involved, the paper took a superior tone referring to the ‘panic’ and ‘excitement’ in foreign parts before smugly concluding that the belligerents would both need supplies of coal and iron which Britain was well placed to provide. Actually it didn’t work out that way because later in the year the paper was reporting thin order books among the Sheffield ironmasters due to the war. In turn, this was to have an effect on coal production.

There was plenty of anti-war sentiment about even though Britain wasn’t involved and this allowed the paper to adopt a sarcastic tone. At one anti-war meeting, Mr Odger a ‘workingman’s delegate’ and a pacifist, was reported as saying that in his capacity as a Christian ‘he opposed all war’ and as the paper noted, ‘proceeded to give his idea of Christianity by shouting that he hated Emperor Napoleon as he hated hell and hated King William of Prussia no less’.

On the domestic front once more, the paper reported a meeting of the Manchester Steam Users’ Association. This worthy body, essentially an insurance and inspection organisation for boiler safety, noted that in the previous two months there had been 13 explosions with 12 dead and 20 injured. Fortunately, none had occurred at premises ‘owned by members of the association’. Four of these explosions were attributed to a lack of water in the boiler. The owners might well have been advised to check the advertisements placed in the paper by the Patent Whittle Boiler Company of Walsall. The company advertised regularly in the Guardian and always included a line drawing showing the ideal high water level for a boiler. Below was another line labelled ‘low water, commencement of danger’ and below that a red line marked ‘danger’, the point at which those non-members of the Manchester Steam Users’ Association got themselves into trouble. The diagram was described as being ‘important to coal masters & others employing steam power’. In the 1870s, with safety regulations at a minimum, this was something of an understatement.

Many of the advertisements are baffling to the untrained eye. Casartelli’s ‘Celebrated Transit Circumferator’ may have been a surveying instrument but this was not explained. Ommanney and Tatham’s ‘Direct Double Acting Horizontal Pumping Engine’ is a rather long winded name but accompanied by a detailed line drawing at least shows the reader exactly what it does. The New Conveyor Company felt compelled to advertise its coal screening machinery with an illustration flanked by two kilted Highlanders in bearskins. Geography cannot have been the reason since this was a London company.

Walker’s ‘Improved Hook’ (‘prevents over winding’) was a device that might have saved a life at Pendleton Colliery in Lancashire. The case was heard at Liverpool Assizes where the accused received a three-month sentence for manslaughter, which caused the paper to comment that ‘it hoped the death would lie on his conscience for longer than the sentence’. William Cooper, whose job it was to operate the colliery winding machinery, had been ‘raised from a drunken slumber’ by voices from the bottom of the mine shaft (no telephone communication back then). He went to his engine ‘utterly incapable of managing it’ and proceeded to raise and lower the cage ‘disregarding the signals that those inside gave him to stop the machinery’. The cage was overwound up to the headstock causing a man to fall out and down the shaft.

Of all the various horrible ways to meet one’s end in mining, falling down the shaft would seem to be the easiest to avoid, yet in 1869 the mines inspectors reported that 32 men had managed to do just that. The Victorian mania for collecting statistics caused the inspectors to report in that year that a life was lost for every 126,489 tons of coal raised. The total number of fatalities in mining during the 1870s would have done justice to a small war.

Civil court cases were also covered by the paper. Appearing before the judicial committee of the Privy Council was the Bower-Barff Rustless Iron Company. The owners had acquired a patent soon to expire and sought prolongation of the letters patent. Taking out the legalise, it seems that the company had failed to appreciate the true economic value of the patent they had acquired until it was too late and now sought some more of the action. Speaking on behalf of the Privy Council Lord McNaghten refused the request explaining that the company had missed the boat or words to that effect.

The paper also responded to legal queries from readers, answering questions which clearly had nothing to do with the coal industry or indeed business in general. One answer informed the writer that, ‘the property left lately by will to your wife belongs to her absolutely and you have no power over it. It does not matter that your marriage took place before 1st January 1883’. This being the date when the Married Women’s Property Act became law. The writer felt obliged to use the pseudonym ‘Pluto’, perhaps because his wife was also a reader of the Colliery Guardian.

Natural history wasn’t neglected either. The October 2nd 1870 edition reported the discovery of Orthosaurus Pachycephalus, a new reptile from the coal measures of Northumberland, described as the ‘largest and most perfect reptilian cranium yet discovered in the carboniferous strata’. The report was accompanied by a large line drawing of the fossil head in profile, taking up the whole of the opposite page.

A portent of things to come and an early herald of the coal industry’s decline came in an 1895 edition. It was reported that the Hon. Evelyn Ellis had on July 12th ‘performed the first journey in a petroleum motor carriage in this country’, the cost of fuel being ‘one halfpenny per hour’. The sheer breadth of the miscellaneous reporting was impressive. In one issue came news about the development of iron puddling in Upper Silesia and about the Belgian government concluding that chicory was a ‘perfectly legitimate drink on an equality with coffee and chocolate’. Elsewhere, the Russian military authorities were reported to be breeding carrier pigeons for war purposes and in a new advance that wonder material asbestos was being sent out by Bee’s Asbestos of Kent ‘dry in bags and therefore cheaper than when wet’. Cheaper but a whole lot more dangerous as we now know.

In the case of the Colliery Guardian, the name doesn’t do full justice to the content, since it was far more than a mouthpiece for the coal industry. Considering the size and importance of the industry and the vast amount of reportage needed to cover it, it would have been understandable if the paper had restricted itself to the subject covered by the title. The fact that the Guardian didn’t do so makes the paper one of the less well known archives of life and events in the 19th century.

BILL HARTLEY, a former deputy governor in HM Prison Service, writes from Yorkshire

A fascinating piece, Bill – another excursion into the lost world of old industrial Britain…

I am an ex Colliery Electrical Engineer, I’ve worked in the Northumberland, North Staffordshire, Cumberland and North Wales Coalfields. I am interested in researching some of the pits I worked at, how can I access The Colliery Guardian from the past containing relevant articles? Informative article by the way.