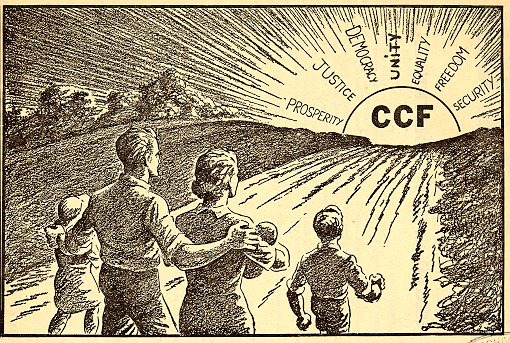

CCF (Saskatchewan Section), Towards the Dawn

Strange Bedfellows in Canada

Mark Wegierski detects a convergence of the “Old” Left and Right

One can look at the New Democratic Party (NDP) in Canada – and its precursor, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) – to highlight the differences between the so-called “Old Left” and the new Left-Liberal consensus.

In the May 2, 2011, federal election in Canada, the New Democratic Party – Canada’s social democratic party – won 103 seats, thus displacing the Liberal Party, and becoming the Official Opposition. However, in the October 19, 2015 election, they were swept away by the Justin Trudeau tide, falling to 44 seats. Some blamed Tom Mulcair’s centrist-tending campaign (especially the promise to keep the federal budget balanced) for this loss.

Tommy Douglas, revered today by many in Canada as the founder of the Canadian Medicare System, was a longtime leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. Like many on the “Old Left”, Tommy Douglas was surprisingly conservative on cultural and social issues. For example, medicare was initially adopted in the province of Saskatchewan as part of a pro-natalist, pro-family policy. Tommy Douglas also advocated what later became called “workfare” – appalled by the idea that able-bodied men should receive government money without rendering some kind of constructive labor. And he hated deficits, arguing that fiscal prudence was necessary “to keep the bankers off the government’s back”.

While ferociously fighting for equality for the working majority, much of the “Old Left” had no wish to challenge religion, family, and nation. They were thus social-democratic in economics, but socially conservative. Indeed, most of the “Old Left” would have found the concerns of the post-Sixties’ Left as highly questionable, if not repugnant.

One could therefore ask the question – do the genuine Left and the genuine Right converge today as an “anti-system opposition”? A number of social critics across the spectrum, such as U.S. paleoconservative theorist Paul Edward Gottfried, and Frankfurt School-inspired Paul Piccone, the late editor of the eclectic, New York-based, independent scholarly journal, Telos, have perceived the ruling structures of current-day society in terms of a “managerial Right” and a “therapeutic Left”. Piccone’s interpretation of the Frankfurt School was unusual as he saw its members as critics of the managerial-therapeutic regime – as opposed to a more common view that they had in fact significantly aided in the institution of the system.

According to Gottfried and Piccone, there currently exists a pseudo-conflict between the officially-approved Right and Left which in reality represents little more than a debate between managerial styles. The “managerial Right,” typified by soulless multinational or transnational corporations (including the big banks and financial firms that a few years ago received over a trillion dollars of U.S. taxpayers’ money) represents the consumerist, business, economic side of the system. The “therapeutic Left,” typified by arrogant social engineers, advocates redistribution of resources along politically-correct lines, and “sensitivity-training” for recalcitrants. Traditionalists and some eclectic left-wingers oppose both the “managerial Right” and the “therapeutic Left,” as together constituting today’s “new Establishment,” or “New Class.”

The Left is also identified today, by some traditionalist and eclectic critics, such as Michael Medved (author of Hollywood vs. America) and Daniel Bell (author of The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism), with the rougher edges of the pop-culture, which similarly seeks to negate traditional social norms. The profit motive of the corporations, and the rebelliousness of the cultural Left and of late modern culture in general, feed off each other. The pop-culture in America and Canada (including certain reckless and irresponsible academic and art trends) and the consumer culture, are tightly intertwined. But the sense of an integrated self and society, where people can hold a meaningful identity, and in which real public and political discourse can take place, is fundamentally in atrophy.

The real division in both the U.S. and Canada, then, is between supporters and critics of the managerial-therapeutic regime. The critics include genuine traditionalists – people who respect religion and concrete, rooted locality, and are able to perceive the assaults of both capitalists and therapeutic experts against them – as well as the communitarian tendency (that was especially prominent in the early to mid-1990s) which emphasizes “real communities” as against corporate and therapeutic manipulations. While some leftists denounce Christopher Lasch as a reactionary, he continued to identify himself as a social democrat to the end of his life.

The possibility of a coalition of the authentic Right and Left against the ersatz Right and Left Establishment conglomerate was anticipated by John Ruskin, the nineteenth-century art critic and social commentator, who – in an age of a pre-totalitarian and pre-politically-correct Left – could confidently say, “I am a Tory of the sternest sort, a socialist, a communist.” G. K. Chesterton, likewise, made pointed criticisms of managerialist and consumerist capitalism, which he presciently noted was based on the premise of unending economic growth which must ultimately destroy nature and thoroughly undermine social mores and human dignity. He defended the broader lower-middle- and working-classes and called for more local and human-scale systems of economy.

In the wake of the financial and economic crises that engulf the planet today, both Right and Left should look to some of their more unconventional thinkers for guidance on how we can emerge in better condition from these troubled times.

Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and historical researcher

Like this:

Like Loading...

Strange Bedfellows in Canada

CCF (Saskatchewan Section), Towards the Dawn

Strange Bedfellows in Canada

Mark Wegierski detects a convergence of the “Old” Left and Right

One can look at the New Democratic Party (NDP) in Canada – and its precursor, the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) – to highlight the differences between the so-called “Old Left” and the new Left-Liberal consensus.

In the May 2, 2011, federal election in Canada, the New Democratic Party – Canada’s social democratic party – won 103 seats, thus displacing the Liberal Party, and becoming the Official Opposition. However, in the October 19, 2015 election, they were swept away by the Justin Trudeau tide, falling to 44 seats. Some blamed Tom Mulcair’s centrist-tending campaign (especially the promise to keep the federal budget balanced) for this loss.

Tommy Douglas, revered today by many in Canada as the founder of the Canadian Medicare System, was a longtime leader of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. Like many on the “Old Left”, Tommy Douglas was surprisingly conservative on cultural and social issues. For example, medicare was initially adopted in the province of Saskatchewan as part of a pro-natalist, pro-family policy. Tommy Douglas also advocated what later became called “workfare” – appalled by the idea that able-bodied men should receive government money without rendering some kind of constructive labor. And he hated deficits, arguing that fiscal prudence was necessary “to keep the bankers off the government’s back”.

While ferociously fighting for equality for the working majority, much of the “Old Left” had no wish to challenge religion, family, and nation. They were thus social-democratic in economics, but socially conservative. Indeed, most of the “Old Left” would have found the concerns of the post-Sixties’ Left as highly questionable, if not repugnant.

One could therefore ask the question – do the genuine Left and the genuine Right converge today as an “anti-system opposition”? A number of social critics across the spectrum, such as U.S. paleoconservative theorist Paul Edward Gottfried, and Frankfurt School-inspired Paul Piccone, the late editor of the eclectic, New York-based, independent scholarly journal, Telos, have perceived the ruling structures of current-day society in terms of a “managerial Right” and a “therapeutic Left”. Piccone’s interpretation of the Frankfurt School was unusual as he saw its members as critics of the managerial-therapeutic regime – as opposed to a more common view that they had in fact significantly aided in the institution of the system.

According to Gottfried and Piccone, there currently exists a pseudo-conflict between the officially-approved Right and Left which in reality represents little more than a debate between managerial styles. The “managerial Right,” typified by soulless multinational or transnational corporations (including the big banks and financial firms that a few years ago received over a trillion dollars of U.S. taxpayers’ money) represents the consumerist, business, economic side of the system. The “therapeutic Left,” typified by arrogant social engineers, advocates redistribution of resources along politically-correct lines, and “sensitivity-training” for recalcitrants. Traditionalists and some eclectic left-wingers oppose both the “managerial Right” and the “therapeutic Left,” as together constituting today’s “new Establishment,” or “New Class.”

The Left is also identified today, by some traditionalist and eclectic critics, such as Michael Medved (author of Hollywood vs. America) and Daniel Bell (author of The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism), with the rougher edges of the pop-culture, which similarly seeks to negate traditional social norms. The profit motive of the corporations, and the rebelliousness of the cultural Left and of late modern culture in general, feed off each other. The pop-culture in America and Canada (including certain reckless and irresponsible academic and art trends) and the consumer culture, are tightly intertwined. But the sense of an integrated self and society, where people can hold a meaningful identity, and in which real public and political discourse can take place, is fundamentally in atrophy.

The real division in both the U.S. and Canada, then, is between supporters and critics of the managerial-therapeutic regime. The critics include genuine traditionalists – people who respect religion and concrete, rooted locality, and are able to perceive the assaults of both capitalists and therapeutic experts against them – as well as the communitarian tendency (that was especially prominent in the early to mid-1990s) which emphasizes “real communities” as against corporate and therapeutic manipulations. While some leftists denounce Christopher Lasch as a reactionary, he continued to identify himself as a social democrat to the end of his life.

The possibility of a coalition of the authentic Right and Left against the ersatz Right and Left Establishment conglomerate was anticipated by John Ruskin, the nineteenth-century art critic and social commentator, who – in an age of a pre-totalitarian and pre-politically-correct Left – could confidently say, “I am a Tory of the sternest sort, a socialist, a communist.” G. K. Chesterton, likewise, made pointed criticisms of managerialist and consumerist capitalism, which he presciently noted was based on the premise of unending economic growth which must ultimately destroy nature and thoroughly undermine social mores and human dignity. He defended the broader lower-middle- and working-classes and called for more local and human-scale systems of economy.

In the wake of the financial and economic crises that engulf the planet today, both Right and Left should look to some of their more unconventional thinkers for guidance on how we can emerge in better condition from these troubled times.

Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and historical researcher

Share this:

Like this: