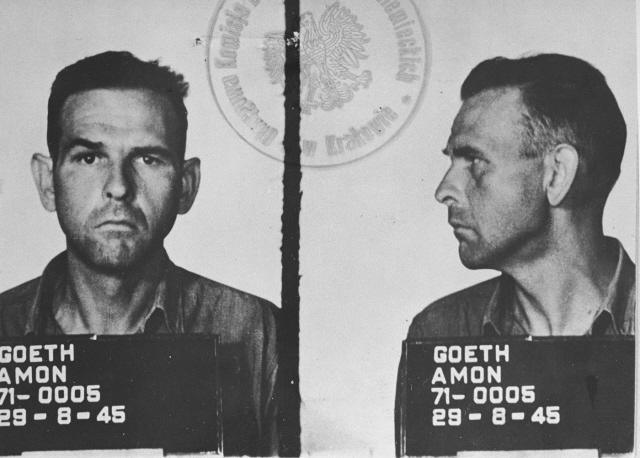

Amon Göth, 1945, credit Wikipedia

Meet the Ancestors

Ed Dutton enjoys a fascinating memoir

My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family’s Nazi Past . . . by Jennifer Teege and Nikola Sellmair. Translated by Carolin Sommer. 2015. Hodder and Stoughton. Hardback. 221pp.

Over the last twenty years, a niche genre has developed in German popular literature: the relatives of senior Nazis pen their own autobiographies, focused on how their family dealt with the shame of being descended from prominent Hitler-supporters, how the authors feel about it, and how they have attempted to make amends for the crimes of their ancestors, for which they hold some hereditary guilt. A couple of these, such as The Himmler Brothers, by Himmler’s great niece Katarin Himmler, have been translated into English. The lives and feelings of these Nazi descendants seem to make compelling reading. We are impressed by those who have interesting ancestors, yet vaguely aware that personality is partly genetic. As such, the descendants of eminent Nazis both attract and repel us. They provoke our hope (perhaps their ancestors’ actions were mainly a function of environment) and our fear: maybe they were essentially a function of genetics. The authors struggle with the same hopes and fears. These are exciting combinations for a popular book.

Jennifer Teege’s newly translated autobiography My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me is, in many ways, more compelling than others in this genre, not least because the author is mixed race. Half German and half Nigerian, Teege’s mother was a mentally unstable and dysfunctional woman who subsequently married an abusive husband. Born in 1970 in Munich, Teege was raised in a Catholic children’s home until the age of 3, having semi-regular contact with her mother and her mother’s mother until the age of 7, when she was adopted by her educated, white foster family who then stopped her biological family from keeping in touch. When she was 20, her half-sister, by the abusive father, tracked her down and she ended-up meeting her biological mother, but there was no great bond between them and they lost touch.

Then one day, when Jennifer was 38 and married with children, she was in Hamburg Library when she happened to pick up a book called, I Have to Love My Father, Don’t I? by Monika Goeth. Looking through it, she realised that this was her biological mother. In fact, she recalled that she was once ‘Jennifer Goeth.’ Reading the book, she made a horrifying discovery. Her grandmother, whom she recalled with affection, had been the common law wife of Amon Goeth, commandant of the Plaszow concentration camp. This was no ordinary German war criminal. This was the commandant who had been portrayed, only a few years earlier, by Ralph Fiennes in Schindler’s List; the one who shot Jews from his balcony for fun; the so-called ‘Butcher of Plaszow.’ This revelation sent Teege, who we later discover had long suffered from mental illness anyway, into a long depression in which she obsessed with discovering everything she could about her grandfather. She goes on pilgrimages to former Nazi concentration camps in Poland and become wracked with guilt about the actions of her infamous ancestor.

The book is divided into two interspersed narratives, which is confusing at first but the benefits eventually become clear. On the one hand, there is Jennifer’s memoir, centred around the discovery of her forebear. Much of this is written in the present tense, as if she’s going through it all again as some kind of regression therapy. Then there is the broader historical narrative, written by her co-author, which includes interviews with Jennifer’s friends and relatives. This contrast eventually works quite well, meaning that neither part of the book becomes stale. It also means that the book genuinely presents Jennifer’s own words, rather than those of a ghost writer.

It seems unlikely that Goeth would have shot his grandchild. Jennifer’s assertions that this is so dismisses any attempt to understand Amon because his last words (before being hanged on the third attempt) were ‘Heil Hitler.’ However, this rather contradicts her later emphasis on the importance of blood to love. It is likely that her grandfather would have loved her, evil as he was to those outside his in-group. The translator has also chosen to make the title more emotive than the German version, which was merely ‘Amon’ and then the main title used in the English version.

But, overall, the autobiography is fascinating reading, even beyond the author’s discovery and its psychological aftermath. Jennifer’s insights into how it feels to be raised in a children’s home and how it feels to be an adopted child, especially a mixed race one adopted into a white family who already have two of their own biological children, are informative and poignant. She insists that you not only feel unwanted (as you have been given away) but you know that your adoptive parents, deep down, are bound to love their own children more than you. You feel, constantly, that you must earn their love and that it cannot be taken for granted. You are likely to be in the intellectual shadow, she explains, of your parents and their biological children. She observes that children such as her tend to suffer from mental illness and strongly rebel as teenagers, making this biography potentially invaluable, in that mixed race adoption appears to be a growing phenomenon. Teege, though perhaps slightly self-absorbed at times, is also an intriguing woman, independent of her circumstances and family tree. Before she knew about anything about Amon Goeth, she had lived in Israel, learning fluent Hebrew and obtaining a degree, taught through Hebrew, from Tel Aviv University. Her memories of life in Israel are very readable, and she ruminates, years later, over how to break to her Israeli friends whom she has discovered she really is. Interestingly, they comment that it would have been difficult to be her friend had she known (and told them about) her grandfather when she was in Israel.

This is a thought-provoking book that is well-worth reading both as examination of how it feels to descend from a notorious Nazi and of what it is like to experience interracial adoption.

Dr Edward Dutton is Adjunct Professor of the Anthropology of Religion and Finnish Culture at Oulu University

The term ‘Polish concentration camps’ is incorrect. The German Nazis established the ‘concentration camps’ on occupied Polish soil. The camps were not Polish as implied by the comment. Please correct the error.

The professor of the “Anthropology of Religion” obviously flunked World War Two history. There were no “Polish death camps,” only Polish victims (who were the first to be imprisoned in the camps). Germans killed three million ethnic Poles both inside and outside the camps in German-occupied Poland. What a lack of respect.

“Polish concentration camps”????

It was Germany that established 42,500 concentration camps and ghettos (according to U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum) in Germany and occupied countries. Therefore they were all German. Please remove this offensive expression ASAP!! Thanks in advance.

I am surprised to see that a professor of Anthropology has made such an obvious error in stating that there were “Polish concentration camps” …there are no such places. Please make a correction to your article..the camps were Nazi German concentration camps in Occupied Poland.

It is lazy and inaccurate to call Nazi German concentration camps in occupied Poland Polish camps. A dangerous slippage, which rewrites history

In your article you use the term incorrect and deceitful term “Polish concentration camps” while referring to the concentration camps run by Germans in the Third Reich (Germany) and occupied Poland (e.g. Auschwitz and the surrounding area has been annexed during 1939 as has been part of the Third Reich until 1945; other parts of Poland, like the General Government have been occupied by the Germans).

I guess you would not write about “American attacks on the WTC”.

Please correct this deceitful term on your website ASAP

Yours faithfully,

Aleksander Jarosz

The concentration and extermination camps were established in occupied Poland by the Germans to torment and murder Polish citizens, both Jewish and Christian. It is wrong and offensive to describe them as being “Polish”.

Just to be clear – there is nothing like “Polish concentration camp” in the whole world. You can find ONLY GERMAN NAZIS concentration camp established in occupied Poland. Here is reliable source about when you can learn TRUE: http://auschwitz.org/en/. The use of the such term withour adding who did it is insulting and hurtful to the Polish people.

Why are you shifting the responsibility of murdering million of lives from the German to the Polish people. Why are so cruel to Poles?

Do you know that 3 000 000 Poles were murded during WWII by Germans?

And one more thing – they were so called Nazis and they came from GERMANY.

Please correct and respect history! And all othose innocent people murdered there!