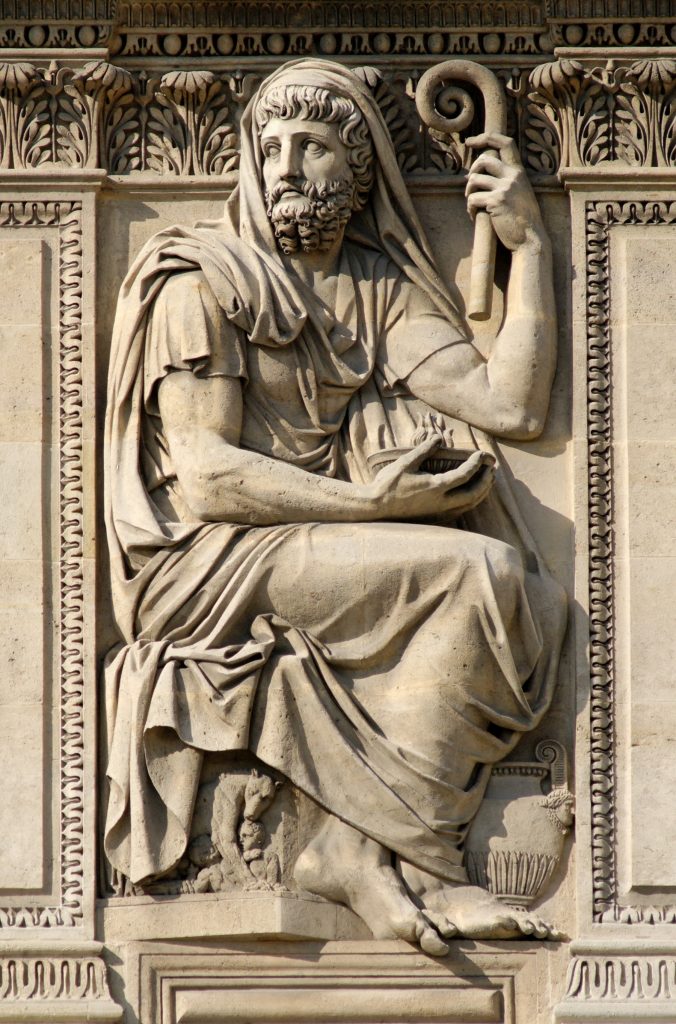

Relief Herodotus, Cour Carré, Louvre

Herodotus, in the Eye of the Beholder

Darrell Sutton salutes the latest edition of The Histories

Herodotus: The Histories, 2013, Translation by Tom Holland, Introduction and Notes by Paul Cartledge. Paperback edition, Penguin, 2015, ISBN 978-0143107545, Pp.834

Herodotus (c.484 BC – c. 420 BC) was not a writer of poetry; he wrote prose, and for this act of kindness students of classical Greek should be grateful. Was he the world’s first historian? One individual maintained this view. Cicero’s (106 BC-43 BC) influence in late Republican Rome was immense, in the centuries which followed his death he became a literary icon, the standard for judging what was proper and improper in the writing of Latin. Still, he did not know that his designation of Herodotus, as ‘The Father of History,’ would become a timeless ascription. Herodotus’ account of the Graeco-Persian Wars supports the credit traditionally attributed to him. The Western world is indebted to him. He taught successive generations that all wars have causes and consequences. This is good news for folks who are trying to come to terms with tribal genocides in Africa, global jihadism, political murders, and other hostilities in the newspapers each day.

Some good, and not so good, scholars took time through the years to give Herodotus’ texts an English appearance. He has spoken through many voices. Quite naturally, through all of them Herodotus speaks with an accent. Of late, Tom Holland joined with Paul Cartledge to take up this task, and their joint venture culminated in the issuance of Herodotus: The Histories (2013). The book itself is beautiful. Since it now is in the marketplace in 2015 as a paperback, thousands of readers can pose new questions while reading through this translation of a ‘classic’ text. Herodotus’ historical researches are foundational to Western Civilization. His comparative studies of ancient societies in the environs of Mediterranean districts were original. But post-Enlightenment historians have not been too kind to his type of history writing.

The depreciation of Herodotus since the Siècle des Lumières stems partly from scholarly acknowledgement of his many superimposed theological motifs. The existing appreciation of secularism in university and college settings is a construct unsuitable for theological asides – even if they are embedded in ancient texts of foreign language. It is for this reason Thucydides was accepted as a more judicious writer of historical events. His writing gives the impression he was unconcerned with the gods. One must remember that Thucydides work was irregular; but Herodotus’ outlook represented the norm of historical genres of all ancient societies. It was believed that the gods were for or against people. So in the various phases of Early Antiquity, the eight century period preceding Augustus (63BC – AD 14), the gods were thought to be characters who helped mankind or thwarted humans’ wayward plans. To be sure, Herodotus was not the critical writer moderns would like him to have been, but who cares? Contemporary critics can do their own criticism of his writings. They are well-equipped to conduct researches of this sort. What we needed, and what Herodotus has given us, are the facts as an ancient knew them or accepted them. From those facts ‘we’ can reinterpret, clarify, correct or deduce truth and error while studying his narratives.

This kind of Herodotean criticism is not unusual. O. Kimball Armayor published more than one article in the 1970s and 1980s outlining his view that Herodotus did not visit the places he said he visited or see the things he said he had seen. I did not find his point of view credible. For that reason, the distrust Armayor had for Herodotus’ details I came to have toward Armayor’s conclusions. His cynicism seemed extreme to me; nevertheless, staring me in the face even now is Detlev Fehling’s mass of Herodotus’ alleged misstatements in Herodotus and His Sources: Citation, Invention and Narrative Art (1989).

The recovery of Herodotus’ reputation, and the renewed study of his histories, is on-going – a boost certainly was given to his repute in 1958 through Arnaldo Momigliano’s (1908-1987) erudite essay ‘The place of Herodotus in the History of Historiography’ and by W. Kendrick Prichett’s (1909-2007) volume The Liar School of Herodotus, a 1993 commentary which opposes Fehling’s main arguments. As can be seen, many persons have attempted to aid Herodotus in the art of correct speech. This is a flourishing field of studies: Holland and Cartledge’s translation is some recent evidence. Fostered primarily by Hellenists whose abilities are distinguished, many of them have sought after Homeric clues in the Greek text, or preferred links to Greek tragedy. Overlooked is the fact that Herodotus’ text is the result of that medley of international connections which led to the development of the Ionic dialect. A Potpourri of languages undoubtedly was familiar to him.

As accustomed as I am to reading ancient Near Eastern material, the Greek terms he uses do not seem to me to be proof of the author’s ignorance of the source-languages of the people he describes. On the contrary Cartledge asserts, “H. could not himself speak or read Persian, so – if these stories are not indeed pure invention – he must have had them either from a Greek-speaking Persian source or a Persian-speaking Greek source, or sources”, p.641. I cannot agree at all with Cartledge’s assumptions. Taken as a whole Herodotus’ verbiage, to me, reflects an acquaintance more or less so with various Near Eastern expressions: e.g. for the Greek text at 2.46.4, Holland translates, “In Egyptian Mendes can mean both ‘male goat’ and ‘Pan.’” (p.128). Moreover, in my opinion Herodotus’ reports are too comprehensive to be mere hearsay: to cite another example, out of his own mouth come these words, “I witnessed something truly extraordinary there, which I was tipped off about by the locals” (p.193).

I thought it might be nice to have my trusty two-volume Oxford Classical Texts (1927) edition of Herodotus nearby while reading the new translation. Edited by Charles Hude, this is the edition upon which the new translation is supposedly established (p.xxxix). However, in a little while I realized that the two-volume edition would be of little use since the English of Holland’s version seems to be indistinctly linked to the grammar and fine distinctions of the Greek. When I read the first lines of book one,

Herodotus, from Halicarnassus, here displays his enquiries, that human achievement may be spared the ravages of time, and that everything great and astounding, and all the glory of those exploits which served to display Greeks and barbarians, alike to such effect, be kept alive – and additionally, and most importantly, to give the reason they went to war.

and afterwards last lines of book nine,

But Cyrus, when he heard this proposal, found it less than wonderful; he told the Persians to put it into action by all means, but advised them to prepare themselves, should they go ahead, to be rulers no more, but ruled instead. ‘Soft lands are prone to breed soft men. No country can be remarkable for its yield of crops, and at the same time breed men who are hardy in war.’ So convinced were the Persians by this argument that they took their leave of Cyrus, and opted – now that his judgement had proved superior to their own – to live in a harsh land and rule rather than to sow a level plain, and be the slaves of others.

I knew that only by small measures was I in the vicinity of the connotations of the original text. That is not a complaint; Mr. Holland’s free-renderings are of a composite nature, seemingly making use of English translations to a greater extent than the Greek texts. The book is a solid piece of work. It should be purchased by all who desire to read Herodotus. Indeed several gifts are needed when offering interpretations of a work like Herodotus,’ and Mr. Holland has his fair share of them. Specialism in the latest critical researches of Egyptologists, aspects of Hittitology, and in ancient Persian literature is helpful for confirming and/or refuting some of Herodotus’ outlandish claims regarding ‘flying snakes’ (2.75) or the birth of a lion cub to Meles’ concubine (1.84). Then again, the genius of Herodotus’ specialist abilities is not noticeable at all times through the translation. What is obvious is a lively writing style, a capacity for drawing allusions, and depicting ancient reports with a bit of panache. Holland displays these with ease.

For example 4.64 one reads,

War, as practised by the Scythians, has a number of distinctive characteristics. When a Scythian records his first kill, he will gulp down the man’s blood. He will also bring the heads of those he has killed in battle to the king, for a head will secure him a share of

Scythian metalwork, National Museum of Ukraine

whatever booty may have been won. …The head itself is scalped… There are many Scythians who wear cloaks fashioned out of scalps… A common practice as well is to take the corpse of an adversary, to skin the right hand, fingernails and all, and then to make it into a cover for an arrow-sheath. (Human skin, it turns out, is thick and has a tremendous sheen, more brilliant, and whiter, than almost any other kind of skin). There are also many Scythians who will flay men entire, and stretch the hides on wooden frames, which they then carry around with them on their horses (p.285-6).

So much for the profit which accrues by means of the translation. A sense of balance is given to the whole by the second of the duo. Professor Cartledge’s introduction is appropriately written in nine parts, and along with his notes to each of the nine books, it is what one would expect of a celebrated Greek scholar. He is not wordy. His explanations are precise. Altogether the explanatory notes total 1067. Each of them is worth reading; Holland’s translation would be less exact without them. Therefore the clarifications are a necessity. And wherever Holland’s renderings may mislead the reader, Cartledge is quick to get the reader back on track. Of the multitude I select two: (p.641) at the outset of book one, notes 4 and #8 give alternate renderings of Greek terms.

Of the former Cartledge writes “reason: The Greek word aitiê, translated here as ‘reason’, could also mean ‘responsibility’, implying assignation of blame”;

Of the latter he writes: “the rape of Helen: This is by no means the only, or the most accepted, version of the origins of the Trojan War. The Greek word harpagê meant literally ‘seizure’ or ‘abduction’ and was something of a euphemism”.

I know of no other edition whose maps are as helpful or whose glossary is as fulsome: over 550 items are defined. For those who enjoy the sleuth work of fact-checking Herodotus’ Greek text, this volume will be of immeasurable value. Armchair readers, those recreational lovers of forceful English prose, will be pleased as well. Undergraduates with a sound guide will read through this with delight; pupils required to indulge society’s contemporary tastes for classics-in-translation have reason to rejoice too.

However, for those whose predilections are for a careful and exact English gloss of Herodotus’ Greek text, the experience may be perplexing by degrees. So keep at your side David Grene’s Herodotus: The History (1987) and the Norton Critical Edition, Herodotus: The Histories (2013, 2nd ed.), and read it alongside the Holland/Cartledge version.

Darrell Sutton is rector of the Tabernacle in Red Cloud, Nebraska, a small village in the Great Plains. He also teaches Semitic languages and edits an academic bulletin entitled ‘The DS Commentary on Books’