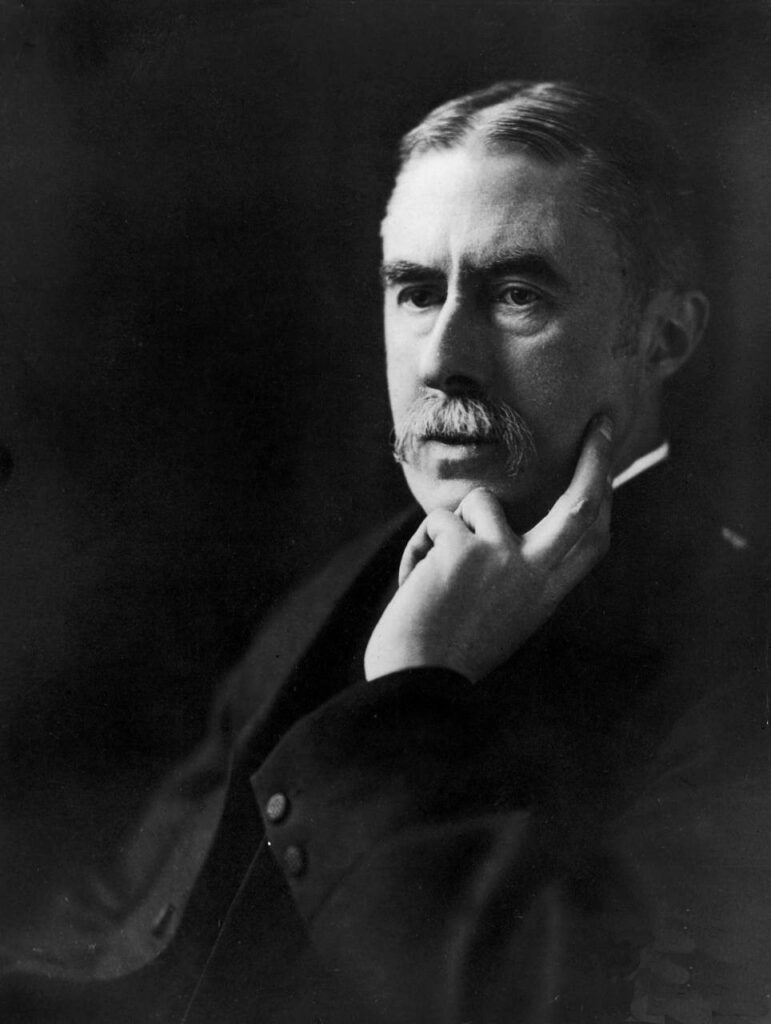

A. E. Housman

Half-Way Through the Plains

A Study of More Poems XXXV, by Darrell Sutton

Half-way, for one commandment broken,

The woman made her endless halt,

And she to-day, a glistering token,

Stands in the wilderness of salt.

Behind, the vats of judgment brewing

Thundered, and thick the brimstone snowed;

He to the hill of his undoing

Pursued his road.

Over the last seven decades several learned commentators have remarked upon the religious poems created by Housman, particularly those based on Biblical texts. An assemblage of those poems, and comments about them made by able literary critics, would comprise three thousand pages or more. Housman was a professed unbeliever in any deity. Many scholars have considered the reasons for an atheist’s fascination with holy scripture. Among them was Carol Efrati who published ‘Housman’s Use of Biblical Narrative‘, in A. Holden, J. Birch, A.E. Housman: A Reassessment (1999). There is much to admire in the essay, and her brief exposition of More Poems XXXV is relevant to ongoing discussions of the poem. But her handling of the text is eisegetic, and she does not go into the details of the structure of his verse.

Another examination is in order, I believe. Housman’s poem presents a picture of Lot, his wife, and the remembrance of them. The tale to which the poem alludes seems a strange basis upon which to originate a poem. Housman, however, thought otherwise, drawing together a compilation of ideas. The Gospel of Luke, 17:32, contains three short words, ‘Remember Lot’s Wife’. To this command of Christ, Housman was obedient – but not in the way originally intended by the first century AD Jewish rabbi. Wide-ranging thoughts led Housman to meditate on [literary] matters in the past, present, and future. The poems he composed encompass all three timespans. In poetry, he read widely. His interests took him into ancient Mesopotamia, Egypt, the texts of Greece and Rome, through medieval intervals, onward to the Romantic Poets and Victorian writers and their habitations. Several of Housman’s poems throw open wide the windows of history. Through carefully crafted lines of verse the characters drawn by him are fixed in readers’ memories. Many of his sentences are unforgettable. Who does not love the ‘blue remembered hills’ in ‘the land of lost content’? Besides, the recollected fields of yore were fertile grounds in which to plant the seeds of his fecund ideas. Some seedlings appeared in A Shropshire Lad and in Last Poems, then again in More Poems.

In the case of MP XXXV, Housman’s reading of the account in either the Authorized Version or Revised Version evoked feelings in him that generated the above lyrics that are vivid and forceful, but often overlooked in studies of his published poetry. Scriptures attest to the wickedness of Sodom in many places (e.g., Deut. 32:32; Isa. 1:10, 3:9; Jer. 23:14, 49:18, 50:40 and Ezek. 16:49). Readers of the poem who are unfamiliar with the context of the story in Genesis may not appreciate the lively descriptions.

But the poem itself tells a rather good story, containing flashes of brilliance and touches of satire. Housman places the events in a new light and holds them up to ridicule. What might surprise students is that Housman’s patterns and cadence do not stand far and away from what is typical in Hebraic psalmody. Yes, the somber tone is there: commandment and its transgression are noted, and judgment follows with unrelenting pathos. All told, Housman’s tale is a singular expression of grief. As for the actual narrative recorded in Genesis 19, the preserved, canonical text maintains that

Lot departed Mesopotamia with his uncle Abram, went to Haran, and later settled in Canaan. The two of them were wealthy. But owing to disagreements between his herdsmen and those of Abram, the latter advised them to go their separate ways. Lot settled in the plains of Sodom and Gomorrah, eventually becoming a leading citizen of Sodom. Indiscretions followed. Angels arrived to warn Lot of the judgment to come. As residents, two of Lot’s daughters married men of Sodom. Homosexuality was accepted and pervasive within the township. Angels instructed Lot, his wife and his two daughters to flee the municipality, not looking back for any reason. Lot’s wife decided to cast her eyes backwards in the direction of the fiery destruction of the city and immediately was turned into a pillar of salt. Lot and his daughters escaped to a nearby mountain. There his daughters deliberately made him drunk with wine, then took turns having intercourse with him. Awaking from inebriation, Lot was unaware that he engaged in incestuous activity.

It is little wonder that few poets before 1900 composed verses about Lot’s escape or have commented on Housman’s poetic version of it. The story is beset with controversial elements: divine judgment, incest, etc. Anyone in this day and age who disparages the verity of the account runs the risk of being deemed anti-Jewish or anti-Semitic. Commentators who criticise today the Sodomian culture of the plains run the risk of being described as homophobic. Moreover, individuals who receive the biblical account as true-to-fact likely will be labeled naïve or unscientific. The quagmire is filled with tags by which good and bad critics are weighed down and stifled. The story of Lot and his wife is inflammatory in many ways. None of the above would have mattered to Housman. He was bold and audacious, and composed lurid verse as did other poets of his day. For instance, William E. Henley’s (1849-1903) poem, London Voluntaries IV, also contains some striking language,

Out of the poisonous East,

Over a continent of blight,

Like a maleficent Influence released

From the most squalid cellarage of hell,

The Wind-Fiend, the abominable—

The Hangman Wind that tortures temper and light—

Comes, slouching, sullen and obscene,

Hard on the skirts of the embittered night;

In form, basically, it is free verse, with an odd rhyme scheme: ABA CDB AB. The octave has an enjambment at the end of line three. Henley supplies the religious sentiment, one that is shadowy and dark. The wind is the adversary, on the move and on the attack. That ‘maleficent Influence’ hovers over the continent like an indelicate gale, through which the tortuous airstreams sweep in underneath the blackness of nightfall.

In contrast, through forty-five words, Housman paints a different, but no less intense, picture. There is no epigraph. There is no specific time noted, and day or night is not mentioned. From Housman’s perspective, Lot’s wife was no unnamed heroine. But she fell victim to divine abuse; and Lot’s rescue seemed to him to be anti-climactic. In the poem, her new residence holds no allure for contemporary readers. The legend of her death was passed on orally, an image so intriguing that Housman sets it in verse.

COMMENTARY

Line one: Half-way, for one commandment broken, –The first two-syllable word, ‘Half-way’, signals the progress she made, but in the end it was unrealized. The wilderness of salt never was the ultimate destination for Lot or his family. The town of Zoar was the terminus. Disobedience intervened, and his wife now stands motionless in a barren place. Where she was headed was less appealing than what lay behind. New beginnings are not warmly embraced by all.

Line two: The woman made her endless halt, – Housman’s language hints at a motionless existence. Lot’s wife was stopped in her tracks, and her standstill never ended. Indeed, Housman makes her the cause of the pause in her forward motion. By his use of the past tense verb ‘made’, is he implying that she is to be blamed for her stationary grief?

Line three: And she to-day, a glistering token, – A not so subtle transformation occurred. The female escaper became a luminous symbol. And now, with everyday unchanged, the firm saline image tells the same story to onlookers.

Line four: Stands in the wilderness of salt. – Housman’s choice of words accents a type of wasteland. Erect, but unable to run, the one-time woman of the house strikes a dignified pose in surroundings in which she would not stand out- a wilderness of salt; but Housman’s verse does not incline toward the chemical perspectives held by a few scholars of his day which alleged that the form of a woman of salt in that region was merely a salt-crystal formation.

Line five: Behind, the vats of judgment brewing – In line five, the adverb ‘behind’ indicates the shifting of the versifier’s attention to a furious upheaval, heralding the stormy blasts of sulfur now descending. Divine ire is the cause; but divinity offers no relief to those persons abandoned to this cataclysm. God often is blamed by poets for awful things. It was argued recently that Blake (1757-1827) depicted the God of scripture at times as a diabolical fiend: see Paul Miner, ‘William Blake’s Creative Scripture’, Literature and Theology, (2013), Vol. 27, No. 1. Neither Blake nor Housman seemed capable of ridding their minds of England’s official religion.

Line six: Thundered, and thick the brimstone snowed; – The roar of the heavens issued rumbling sounds, accompanied by fiery blizzards. Unreferenced is the fact that people wailed and cried aloud as flesh burned, drowned out by the vicious din in the plain.

Line seven: He to the hill of his undoing – Turning to the calamity awaiting Lot, Housman introduces the site of his downfall. A curious description, seeing that Lot’s desire to dwell in Sodom forged the pathway to the mountain where the remainder of proper familial relations were breached.

Line eight: Pursued his road. – It seems that Lot, like his wife, opted to permit his peculiar inclinations to override his better judgment. He was the worse for them. Selfishness generates self-delusions of grandeur. Lot misconceived the attainment of his prospects devoid of Abram’s wisdom. Housman concluded the poem powerfully with three words. Lot’s getaway was one of action. He chose his own path to and from the greater Dead Sea plains. The biblical account does not presume that he was fated by his God to lose so much. Housman leaves that issue in an ambiguous form. Who it was that paved the road ahead of Lot did not seem to concern Housman as much as his need to highlight Lot’s own pursuit of it.

FURTHER INSIGHTS

The Burning of Sodom, Corot

A.E. Housman’s fascination with Paris is well known from his letters and revealed by his constant visits to that city. But things of French origin can also be admired from afar. And although I have no direct evidence, I surmise that Housman was likely to have been acquainted with Camille Corot’s oil painting of Sodom’s destruction. I will use it as a visual foil for my remarks below. From the picture above one can see that there are sharp features drawn by the artist. And the painting itself serves only as a reader’s focal point as one considers the historical context of MP XXXV. Housman captures the milieu in his poem.

Like Corot, he chooses to focus on certain aspects of the biblical account, omitting other facts, while embellishing the ones he records. The painting illustrates angelic dimensions. A divine rescue at the hands of a seraph with unisex traits puts Lot and his daughters out of harm’s way. Lot’s wife appears as a shadowy statuette, unrecognizable and forsaken. From the top left of the painting another divine being hurls judgment earthward with force. Escape seemed futile with judgement descending in all directions. Corot does a good job at masking the population of Sodom’s ignorance of Lot’s sudden departure.

Housman, on the other hand, inserted no angelic guardian. Four verses treat of Lot’s wife: the lawbreaker. Housman was explicit. God showed no mercy to her: ‘for one commandment broken’, she was stopped. She was not rebuked but punished with a lifeless existence. Prevented from going backwards or forwards Lot’s wife had lived by her own rules. That same compulsion now caused her death. Her mien is nimbly described. She always wanted to shine, so Housman drew an image of a lady who finally succeeded to pallid radiance. Alas it was too late! No one inside or outside the city turned to see her efflorescent image at the time, not even her relatives. Then days turned into months before her final stance was readily seen. By then, who knew her identity, since Housman does not intimate in his verse that any passersby recognized the person to whom the saline figure belonged? From Housman’s pen came an unfeeling exposé.

The poem gives the impression that the deity is cold, lacking sensitivity. Aside from the oral transmission of the account taken from family, Lot’s wife stood alone and disregarded. And that is a theme that Housman subtly puts into the reader’s thoughts: family members move on despite the occurrence of a tragedy. Lot’s natural disregard for his city, culture and wife, indeed for all things behind him, was less important to him than his God.

Another leitmotif lingering in the background concerns the temptation in her heart that was cultivated by the lure of what was left behind. Housman does not reveal if she agonized over her decision. Whatever one’s explanation, in truth she did not think twice about whirling toward Sodom. And on this topic, one is reminded of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s (1807-1882) poem, The Sifting of Peter, in which he writes of one fiendish specter, saying,

Satan desires us, great and small

As wheat to sift us, and we all

Are tempted;

Not one, however rich or great

Is by his station or estate

Exempted.

Peter, surrounded by many enemies and few friends, succumbed to the desire to spare himself the embarrassment of association with his Lord. Therefore, he yielded to the temptation to deny any knowledge of his master. In spite of everything, he lived to tell about it. Lot’s wife was not so fortunate. She died. No lie was told by her. Anyway, to whom could she have spoken it? She was not ashamed of her connection with Sodom. It was not easy for her to leave. Moreover, this detail Housman implicitly stresses. Of note is the fact that she is concerned about a ruined city ‘behind’ her. It is razed from above, and still the wreckage allures her.

At this point, the focus of the poem shifts. Housman now depicts the images in the rear or ‘behind her’ in darker tones. Lot’s wife was warned by angels of terrible and fearsome things to come. She took heed to their words briefly until curiosity got the better of her. A similar sensation must have resided in her husband and in her daughters. They chose to forge ahead, however, despite an opportunity to turn and view up close the heavy hand of their God.

THE POETRY’S PERSONAL ELEMENTS

Housman’s poem is instructive. And in my opinion, he intended readers to consider the implications of their choices. If one’s new road in life differs drastically from previous roads that led to death, why then turn to glance backwards? Move on. Housman’s personal life was not one of unalloyed happiness. As in every case, an individual’s life consists of a series of twists and turns, of moving beyond past successes and failures without looking back. Housman failed to gain honors in ‘Greats’. You would not know of this failing by looking over the pages of his classical scholarship or from reading his poetry. Many men and women who took ‘Firsts’ and ‘Seconds’ were unable to achieve the fame and notoriety he obtained through his poems and scholarly publications. Housman did not eschew evil. He owned a cache of erotica, transgressing many of the commandments of a polite society. Some harsh judgments were made of him. He reaped what he had sowed in private and in public discourse. He attacked scholars and some reciprocated in kind. He showed no mercy. Hardly any was given him. Grudgingly he climbed to the peaks of classical studies where he died, acknowledged by all for his text-critical acuity, but scarcely missed and loved by few.

Housman’s life was attended by grief and sadness. His homosexuality is now common knowledge. To be sure, comparisons are odious. Unlike Lot, Housman had no children, but of his scholarly creations, his primary progeny, the one for which he is mainly remembered – Manilius Astronomicon in five volumes – remains a terra incognita. Few pupils undertake to grasp the content of the Latin text or commentary, confining their perusals to the English introductions. Most students who do, are unable to comprehend why he would give birth to it all at all. The answer is simple: similar to Lot’s example,Housman ‘pursued his road.’

APPENDIX: ORAL ASPECTS OF MP XXXV AND ITS DESIGN

Undoubtedly Housman’s poems were composed by him with dual purposes in mind: namely, for the readers’ visual enjoyments, and to be read aloud for the aural impressions made on hearers. Listening to a poem is unlike reading one. An oral reader of them will know where to stress syllables and add emotive qualities when voicing a poem’s lyrics. Before an audience, the reader can enhance his or her graphic presentation by vocal fluctuations or verbal variations. By accentuating with controlled intensity, each word then is turned into a distinct visual aid.

I will not burden the reader by analyzing every syllable unit in the poem’s lines, although a few statements may illustrate its design better. As for MP XXXV, the punctuation is not complex. There are seven commas, two periods and a semi-colon. Its sound patterns are easy to discern. Everywhere Housman loves rhyming verse. The first two lines include heavy aspirated sounds with the ‘h’ at the beginning of words. The letter ‘w’ of the word ‘woman’ in line two along with the words ‘her’ and ‘halt’ show that Housman endeavored to affect readers’ sounds of pronunciation: in that line, every other word is aspirated. A similar method was used more effectively in ASL I, 1887, where in line twenty-six he wrote,

From Height to Height ‘tis heard;

This specific practice is usual with his type of composition, which is found as well in line seven. Housman was no expert in phonetics, but he made good use of the plosive ‘t’ in lines three and four. In line six, consonantal combinations of ‘th’ in ‘Thundered’ and ‘thick’ added to the emphases of these words’ meanings, the heavy pronounced tones of those words underscoring the visual imagery he sought to implant in listeners’ minds. The sibilant ‘s’ recurs repeatedly in line four (see ‘glistering’ in line three), and produces a whistling sound ideally suited to the region. This feature is not unnecessary where winds whirl about Lot’s wife standing in the wilderness.

Darrell Sutton publishes papers on ancient texts and reviews biblical and classical literature