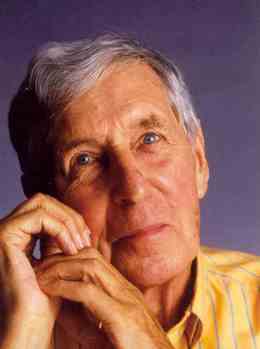

Michael Tippett, credit Wikipedia

Endnotes, March 2022

A portrait of Sir Michael Tippett, by Stuart Millson

Benjamin Britten and Michael Tippett dominated post-war British music. Both pacifists, the two composers shared many musical traits: a love of opera and desire to see British opera gain international acclaim; a delight in folk-music and the setting of poetry in song-cycles. Yet Britten’s reputation and legacy show no sign of diminishing – in part due to the still-flourishing Festival on the Suffolk coast which he founded. Tippett, on the other hand, has faded somewhat from view.

Sometimes controversial in his lifetime, it has been said that few contemporary composers drew as much criticism – for his music, his beliefs, even his clothes – as Tippett; the writer of such masterpieces as the oratorio, A Child of Our Time, Concerto for Double String Orchestra, the opera, The Midsummer Marriage, The Vision of St. Augustine – to name but a few – appears rarely now on concert programmes or radio schedules.

Certainly, during the 1980s, and culminating with the premiere of his large-scale choral-orchestral The Mask of Time at the 1984 Proms, Tippett – for a time – seemed to occupy Britten’s old unofficial position (cemented by his coronation opera, Gloriana) as a favoured Royal composer of national works, such as a Suite for the Birthday of Prince Charles and his contribution – Dance, Clarion Air – to the unaccompanied choral work, A Garland for the Queen. Tippett’s orchestral evocation of an African scene, The Rose Lake, also appeared at the Proms – performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, and conducted by the late Sir Colin Davis, who consistently championed the composer.

Non-conformist

Born in 1905, with a mixture of Kentish and Cornish ancestry, Michael Kemp Tippett came from a well-to-do family imbued with a strong grain of liberal, free-thinking, non-conformist idealism. Early associations with Communism (a common enough trait in the 1930s), with the workers’ educational movement, with Morley College (he was appointed its Director of Music in 1940) placed him, at first, as a figure who seemed to be against the grain of the British establishment – despite finding support from conducting knights, Adrian Boult and Malcolm Sargent – and encouragement from Ralph Vaughan Williams.

This writer first came across Tippett in 1981, quite by chance, on a record-buying expedition. Attracted by a Classics for Pleasure record cover depicting a lonely Norfolk scene (Mousehold Heath by John Crome) and keen to own a copy of the Vaughan Williams Tallis Fantasia– the main work on the record* – we were intrigued by the work on Side 2: Tippett’s Concerto for Double String Orchestra. The name – Tippett – was familiar but not his background or his music. The sleeve notes (by Margaret Archibald) promised of the work “madrigalian freedom”, and I soon became a devotee of the piece; preferring its pulse, pace and thrilling energy to Vaughan Williams’s more slow-moving Tallis Fantasia. And the Concerto’s intensely lyrical middle-movement, with all the moving melancholia of the English string tradition – the solo violin gathering that beautiful melody as if from the air and drawing the rest of the string orchestra into its embrace – I found incomparable.

The Concerto for Double String Orchestra dates from 1939, and for a composer commonly thought of as a writer of “difficult” music, the natural stream of melodious ideas and – in the last movement – the infectious, unstoppable dance-like flow, leading to a triumphant conclusion, carries no sense of the pessimism of the times. In later years, aware of the piece’s accessibility, Tippett described it as his – “pop piece”!

Writing in 1949 in a survey of our native musical tradition, the Dutch musicologist, Marius Flothuis** said of Tippett:

He was especially concerned to produce programmes of unusual music… and devoted much time to pre-classical music, Elizabethan composers, Purcell and others. He made himself a considerable reputation as an authority on his ground, and daily contact with sixteenth-century music had an effect on his own composition, which has elements of the melodic structure and the free and independent metres of the old English madrigalists.

A baroque atmosphere

Another string work, written some 14 years later, also bears the hallmarks of English romanticism, but with an infusion of baroque structure: the Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli. Strongly reproducing Corelli’s music – at least, at first – the 17th/18th-century atmosphere gives way, as the work grows, to another of Tippett’s radiantly “lark ascending”-type sequences. For those who may remember Sir John Betjeman’s BBC-produced film of the 1970s, The Queen’s Realm (a film about English landscape, taken from aerial views, and with poetry and music accompanying each scene), the Tippett Fantasia made an appearance alongside the lines of Milton: “Hail bounteous May that dost inspire youth and mirth and warm desire” – a film of orchards unfolding across the screen.

Nature – more the forces of nature, than mere tone painting – proved to be as profound an inspiration for Tippett as the great human issues of pacifism or political repression (the themes of A Child of Our Time). In his opera, The Midsummer Marriage – given its first performance in 1955 under the baton of John Pritchard – Tippett creates a synthesis of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Magic Flute, legend, ancient magic and Nature-symbolism; the purely orchestral Ritual Dances from the opera sometimes appearing in concert programmes in the same fashion as Britten’s Four Sea Interludes from Peter Grimes. The Ritual Dances, as David Cairns explained in his fascinating synopsis of the opera, published by Lyrita Records*** depict a girl dancer pursuing a boy…

In this first dance – ‘The Earth in Autumn’ – the Hound chases the Hare. The Hare escapes. But in the second dance – ‘The Waters in Winter’ – the pursuing Otter comes very near to catching the Fish, who injures himself against a tree-root. In the third dance – ‘The Air in Spring’ – the Bird has broken a wing and cannot fly. In the end he does not move when the Hawk swoops down on him.

Each dance has a bold, clear, open-air, open-country feel – with an almost supernatural shimmering sense of transformation suddenly produced by a swish of cymbals – the orchestra now sounding as though a rush of wind, or a strange force of primal energy, is coursing through it.

Gamelan influence

Tippett was quite happy to re-use themes and ideas from one work to another. For example, the drum-taps and martial-sounding trumpet section in the third movement of the Suite for the Birthday of Prince Charles appears near the beginning of A Midsummer Marriage; and the portentous timpani strokes, rising above the gamelan-like atmosphere of the late-1970s’ Concerto for Violin, Viola, Cello and Orchestra are summoned, in The Mask of Time. Hearing the same music in different guises often leads to the charge of repetition or recycling, but with Tippett you feel that the technique is absolutely right – the theme sounding fresh and a vital building block of the work in which it is featured.

Quartets, symphonies, vocal music, not to mention an autobiography entitled Those Twentieth Century Blues (my edition contains a photograph of the composer, next to a huge Cornish ice-cream cone), Tippett seems to have shown us every facet of his character. Yet there is one intriguing missing piece of the jigsaw: an unpublished opera inspired by the legend of Robin Hood. The piece dates from the mid-1930s, and it seems safe to suggest that its subject matter might mirror the musician’s political views from that time. Might this lost stage-work be re-discovered and revived by the musical sleuths of the English Music Festival – an institution that has done so much to unearth and restore lost works to our concert programmes and CD catalogues? Whatever the fate of Robin Hood, we can only hope that musicians and audiences alike will find once again the genius of Michael Tippett.

Further listening:

Tippett’s Dance, Clarion Air (part of A Garland for the Queen) will be performed at this May’s English Music Festival, at a concert at All Saints’ Church, Sutton Courtenay, Saturday 28th May, at 2.15pm. (See: www.englishmusicfestival.org.uk)

*Tippett, Concerto for Double String Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Vernon Handley. (On the EMI Classics for Pleasure label, catalogue number 40068, and available in CD format.)

** Modern British Composers, by Marius Flothuis. (Published by the Continental Book Company, 1949.)

*** Tippett, The Midsummer Marriage. Royal Opera House production, Sir Colin Davis, conductor/Lyrita Records. SRCD 2217.

Stuart Millson is the Classical Music Editor of The Quarterly Review

———————————————————————————————

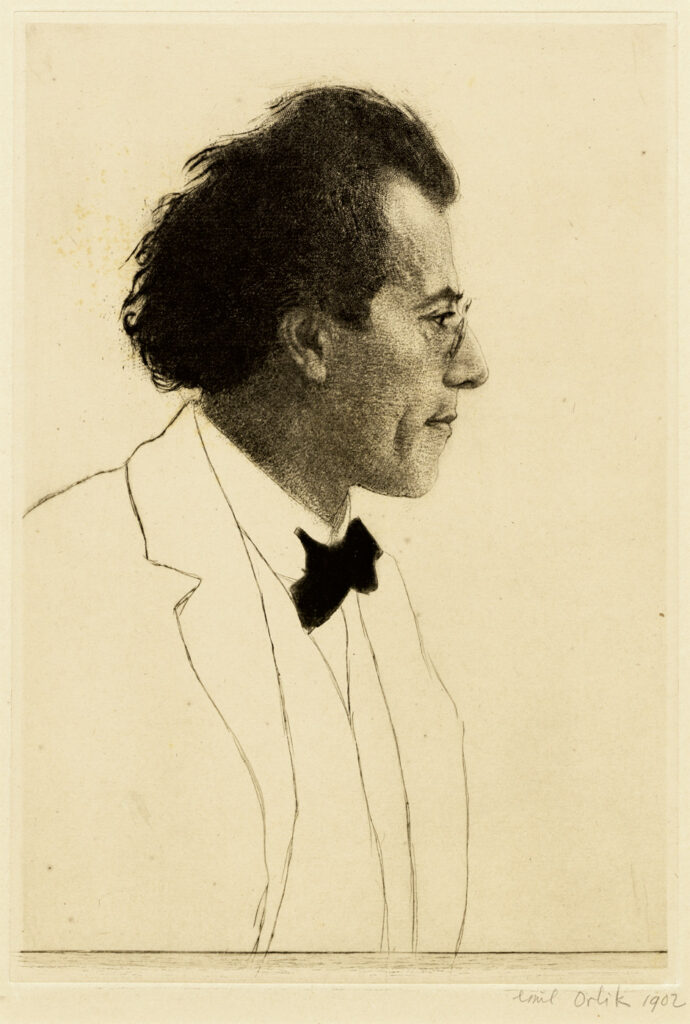

Emil Orlik, Gustav Mahler, 1902, credit Wikipedia

King’s Place, Voices Unwrapped, Aurora Orchestra & Roderick Williams, Songs of a Wayfarer, Friday 25th February 2022, reviewed by Leslie Jones

According to Henry Purcell, music alone has the power to banish care, if only briefly (as in the song ‘Music for a while’, with a setting of a text by John Dryden). Baritone Roderick Williams’ programme at Kings Place provided ample confirmation. Entitled ‘Songs of a Wayfarer’, in reference to Mahler’s ‘Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen’, the theme therein is man as an outcast from nature. ‘How beautiful the world is’, bemoans the wayfarer, ‘but happiness can never bloom for me’.

Williams has the temerity to walk in the footprints of such Mahlerian luminaries as Thomas Allen, Janet Baker and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. In Die zwei blauen Augen von meinem Schatz, he handled the pivotal transition from despair to resignation with aplomb. He has a slight frame but a big heart. His beatific smile and composure bespeak a philosopher manqué.

This was a brilliantly conceived programme, with translations of the four Mahler songs courtesy of Richard Stokes, Professor of Lieder at the Royal College of Music. Thus, Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht anticipated and complemented the Mahler song cycle. Clearly, there is a form of redemption through death. ‘I wish I were lying on my black bier, never to open my eyes again’, proclaims Mahler’s peripatetic journeyman. We were reminded of ‘Cold, illness and birth’, and ‘The unwelcome child and his death-instinct’, two papers by psycho-analyst Sandor Ferenczi (see Sandor Ferenczi-Ernest Jones, Letters 1911-1933, Karnac, 2013).

NB Roderick Williams’ work has featured in previous editions of Quarterly Review, notably his memorable performance in Britten’s War Requiem (see ‘Acts of Mutilation’, November 27, 2018).

Dr Leslie Jones is the Editor of QR

My wife Jan met Michael Tippett, who was her external examiner, during her music and art course at Corsham College. A notably gifted and kind man.