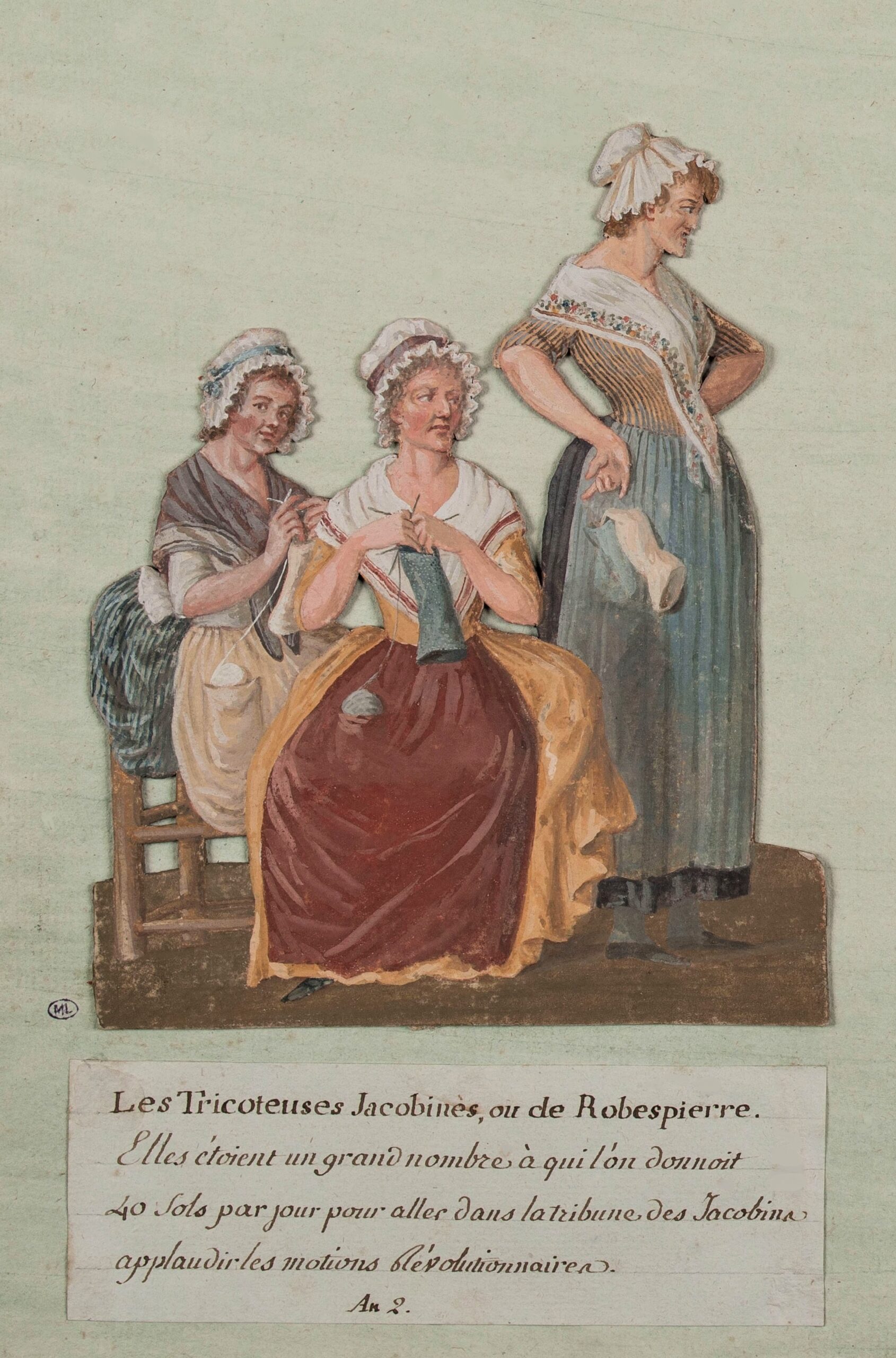

Jean-Baptiste Lesueur (1749-1826). “Tricoteuses”. Gouache sur carton découpé collé sur une feuille de papier lavée de bleu. Paris, musée Carnavalet.

Dialogues des Carmélites

Opera by Francis Poulenc, directed by Barry Kosky, on Saturday 10th June 2023 at Glyndebourne, Lewes, East Sussex; London Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Robin Ticciati; reviewed by David Truslove; performances continue until 29th July

A floor-shaking thud from an amplified guillotine sends a pair of shoes flying across an empty stage. This is the first of 16 gut-wrenching moments portraying the execution of the nuns of Compiègne in the final tableaux of Francis Poulenc’s Dialogues des Carmélites. Presented at Glyndebourne for the first time, Barry Kosky’s new production of this operatic masterpiece, based on a true story, underlines the fears, courage and dignity of a group of Carmelite nuns during the last days of the French Revolution as they face the choice of renouncing their vows or accepting the certainty of death.

Martyrdom is hardly a common operatic subject, or an obvious choice for country house entertainment, especially after last year’s staging here of Poulenc’s absurdly comic Les Mamelles de Tirésias. Yet, as an interrogation of fear and belief, Carmélites (premiered at La Scala, Milan in 1957) develops Poulenc’s religious preoccupations initiated some thirty years earlier in works such as the Litanies à la Vierge Noire and his Mass, both signalling the composer’s return to his catholic faith following the death of fellow composer Pierre-Octave Ferroud in a car crash in 1936.

That violence and beauty can coexist is nowhere better demonstrated in the music of Poulenc, where the juxtaposition between agony and ecstasy has an unforgettable emotional impact. From the urgency of the opening bars, in which phrases are abruptly sheared off, through to the climatic ‘Salve Regina’, the composer assembles a score where Baroque mannerisms combine with echoes of Debussy and Verdi in a compelling mélange of piety and sensualism. Barry Kosky considers Carmélites ‘an extraordinary tango between beauty and pain’.

On the opening night, the Glyndebourne audience gave this production a ringing endorsement. Many, one suspects, were numbed by Kosky’s shock tactics, others overwhelmed by the emotional directness emanating from the performers. Certainly, Kosky intended to cause a stir which, by the second half, began with the collapse of the convent wall prior to an assault by a revolutionary mob baying for blood, soon followed by a line of traumatised nuns submitting to a humiliating haircut – a scene that could have belonged to any wartime conflict over the centuries, not just the Reign of Terror. Most unsettling was the confiscation of their personal effects and habits, prompting uncontrolled hysteria from one terrified nun, her shaking body as disturbingly real as anything recently seen on the operatic stage. Kosky’s visually striking episodes brought us closer to the horror of Robespierre’s regime, and Katrin Lea Tag’s stark, anywhere set – little more than a wide corridor tapered at one end – took us nearer to the austere life of a nun for whom prayer is a prime duty.

The dramatic power of this production depends on well-defined and emotionally focused performances. Leading the cast is Sally Matthews in the role of Blanche de la Force, a young aristocrat turned postulant whose attempts to confront and conquer her fears are finally achieved when she joins her fellow nuns at the scaffold. With a creamy if variable tone, she convincingly portrays a woman beset by anxiety yet determined to control and master her emotions. It is a demanding role to which she brings sustained energy, finding joy and fury when engaging with the spirited and diamond-toned Flora Valiquette as Sister Constance and bewilderment when supporting the painful death cries of the Prioress, Madame de Croissy. The latter’s dark night of the soul is given a commanding performance by Swedish mezzo Katerina Dalayman. Golda Schutz is a bright-eyed and jewel-voiced new Prioress, bringing confidence to her charges, while Karen Cargill as the defiant and maternal Mother Marie is vocally arresting. Paul Gay as Blanche’s father and Valentin Thill as his son constitute a curiously confrontational partnership, assertive vocally, with warmth provided by Gavin Ring as First Commissary and Vincent Ordonneau as the Father Confessor.

The choruses sung by nuns and the militant crowd were powerful and effective, and the London Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Robin Ticciati, drew myriad colours from Poulenc’s lavish score yet avoided the temptation to wallow in its sumptuousness. After the work’s UK premiere at Covent Garden in 1958, The Times wondered whether this opera would ever win a permanent place in the affections of the British public. Judging by its first night reception here, it has.

Editorial endnote; Barry Kosky directed productions of Carmen at Royal Opera in 2018 & 2019. See www.quarterly-review.org/Carmen- Review-Dance-of-Death, Leslie Jones, QR, 8th December 2018; and www.quarterly-review.org/Separation-Anxiety/, Leslie Jones, QR, 2nd October 2019