2001, Revisited

On the fiftieth anniversary of 2001: A Space Odyssey, Mark Wegierski reassesses this epoch making film

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) brought together Stanley Kubrick, one of the most accomplished directors of the cinema, with renowned science fiction writer Arthur Charles Clarke, who wrote the screenplay. 1968, a pivotal years of modern history, was evidently also an extremely rich year for science fiction movies, including also Planet of the Apes. Clarke, the son of a farmer, was born in Minehead, western England, on December 16, 1917. Among his main influences were H.G. Wells and Olaf Stapledon, the author of cosmic histories stretching into the far-future.

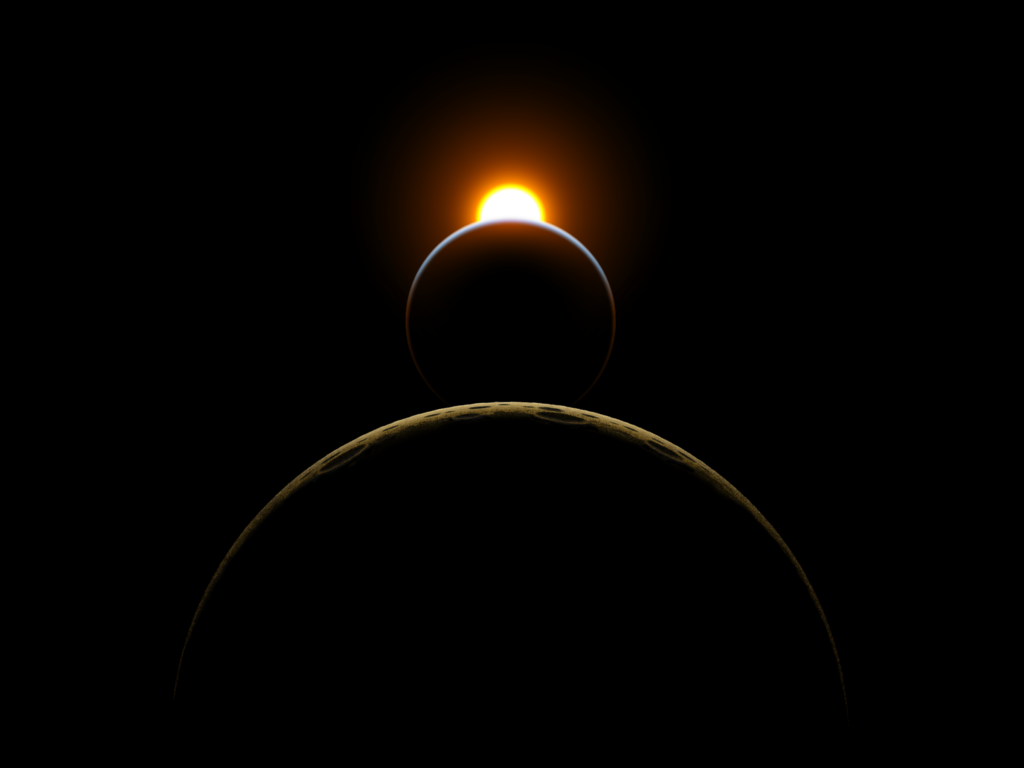

2001 remains unsurpassed. Its special effects and cinematography were groundbreaking. It was one of the first truly intellectually challenging American science fiction films – after decades of mostly b-grade schlock in that genre. A notable feature of the movie is the balletic portrayal of spaceships in flight, accompanied by stirring, classical music.

The opening scene of 2001 is set in prehistory among “ape-men” on the verge of human consciousness. Their life is portrayed as exceedingly hard. Yet love evidently existed, even before the arrival of “the monolith”. We see a sort of Nativity scene, with father, mother, and child. “The monolith” brings increased intelligence to the “ape-men” – but also hatred. The “ape-men” begin to use tools, picking up large bones of animals but malevolently block the path of another group of “ape-men” who wish to drink from a stream. Indeed, the first murder or possibly even genocide is carried out by “ape-men” with enhanced intelligence. The famous incidental music of Richard Strauss’ Also Sprach Zarathustra, inspired by Nietzsche, confirms the idea of a link between reason, “evil” and technology – all of which entail the Nietzschean “will to power”. Representing the leap of millions of years, the large bone thrown into the air is transformed into a spaceship, taking us forthwith to 2001!

Some of the ideas posed by the prologue are problematic for those with a traditionalist outlook. The inevitability of technological progress is suggested. Homo sapiens is depicted as a creature of prey – and little more. Moreover, is the apparent indictment of technological progress also a critique of Western civilisation as such, along the lines articulated at the time by people like Susan Sontag?

The world of 2001 is shown in some detail. There still exist “Cold War” tensions between America and Russia, which have now also been transferred to the Moon, where there are already large bases. The portrayal of life in space and on the moon base is compelling. One example of the attention to detail is a white male astronaut glancing at an issue of Playboy of that year, which incensed feminists. Indicatively, white males remain prominent in the film’s portrayal of the world of 2001.

The third part of the movie involves the voyage of the spaceship and its three-man crew towards Jupiter. It is very realistically portrayed – far from the more-or-less “fantasy” depictions of space travel in Star Trek and (especially) Star Wars. Then commence the problems with the Artificial Intelligence computer, which is guiding the ship.

The fourth part of the movie is a phantasmagoria of surrealism, which allows for varied interpretations. Some see it as essentially the union of human beings with God, which ends with God coming to earth, in the form of the Star Child. In 1953, Clarke had published a novel, Childhood’s End, which enunciated a bleak vision of humanity’s children becoming part of a cosmic supermind, while the despairing adults commit suicide (any further children born would also have become members of the supermind). Clarke maintained a studied ambivalence as to whether this development could be considered as humankind’s evolutionary destiny, or as something more monstrous. Certainly, it is possible to detect ambivalence about “the monolith” in the movie.

Clarke was a Distinguished Supporter of the British Humanist Association and a life-long skeptic about religion. For his funeral, he gave the following instruction:

Absolutely no religious rites of any kind, relating to any religious faith, should be associated with my funeral.

One of his most famous statements, likewise, was:

The greatest tragedy in mankind’s entire history may be the hijacking of morality by religion.

This latter statement arguably shows little understanding of human history. Although many evil actions can be ascribed to religion, the better forms of human behaviour were grounded in religious belief. And Clarke himself clearly believed that only some behavior is truly ethical. He disdained selfishness and pleasure-seeking at the expense of others. Thus it could be argued that Clarke unknowingly partook of an ethical outlook predicated on Christianity.

In one of his most famous short stories, “The Star” (1955), Clarke raises the disturbing quandary for a religious believer that an alien civilization may have been wiped out by a supernova which produced the Star of Bethlehem that heralded Christ’s birth. At the same time, the story brilliantly foresees the anguish that arises around the issue of abortion for Christians living in technologically-advanced societies that have done away with any kind of prohibitions on what becomes merely a routine medical procedure.

Clarke envisaged various technological possibilities. His scientific article of 1945 presaged communications satellites in geo-synchronous orbits decades before it became practically possible. He was also at the cutting edge of speculations in regard to the possible eventual transfer of human consciousness into electronic and machine form, suggesting that this was probably the only way that human beings could achieve millennial lifespans. In the book associated with the film, the Monoliths are represented as such beings.

2001 was based on several of Clarke’s earlier short stories, including “The Sentinel” (1948). He was unhappy that the movie came out before the book, making the latter a novelization of the film. The book also makes it clear that the computer’s “breakdown” arises out of the demands of secrecy imposed by the mission to Jupiter. This could be considered an immanent critique of the “national security state”.

Clarke maintained that “…any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” There are several possible interpretations of this remark, ranging from the putative enslavement of most human beings to technologies of which they have no understanding, to the suggestion that humankind’s powers can be infinitely extended through technology.

In 1989, two decades after the Apollo 11 landings, Clarke wrote: “2001 was written in an age which now lies beyond one of the great divides in human history… Now history and fiction have become inexorably intertwined.” His simple tombstone in Sri Lanka, where he lived for decades, reads: “Here lies Arthur C. Clarke – he never grew up and did not stop growing.”

Mark Wegierski is a Toronto-based writer and researcher

As regular “pub bore & know-all” here, may I recommend the superb, original and unique artwork of Chesley Bonestell, who collaborated with Clarke in “Beyond Jupiter”? His best paintings and drawings, including scenery for “Destination Moon” and “The Fountainhead”, have been collected in a splendid, inexpensive single volume by Ron Miller, though much can be downloaded for wallpaper from Google Images. As a junior member of the British Interplanetary Society, whose own hopes came a cropper when the Spadeadam Rocket Base and Woomera were effectively closed, the Englishman and the American were great adolescent inspirations.

Bonestell’s co-operation with Willy Ley and “V2” Braun helped to incentivize the US space program, though it turned out that his planetary imagination proved in the end rather more interesting and beautiful than God’s own.

And as for Also Sprach Zarathrustra, so spoke the Wellsian Hero at the climax of “Things to Come” – whose Faustian peroration was quoted by Clarke in one of my still treasured books, “It is the universe – or nothing.”

Sorry, but whenever someone starts complaining about white males in classic movies, I love interest.