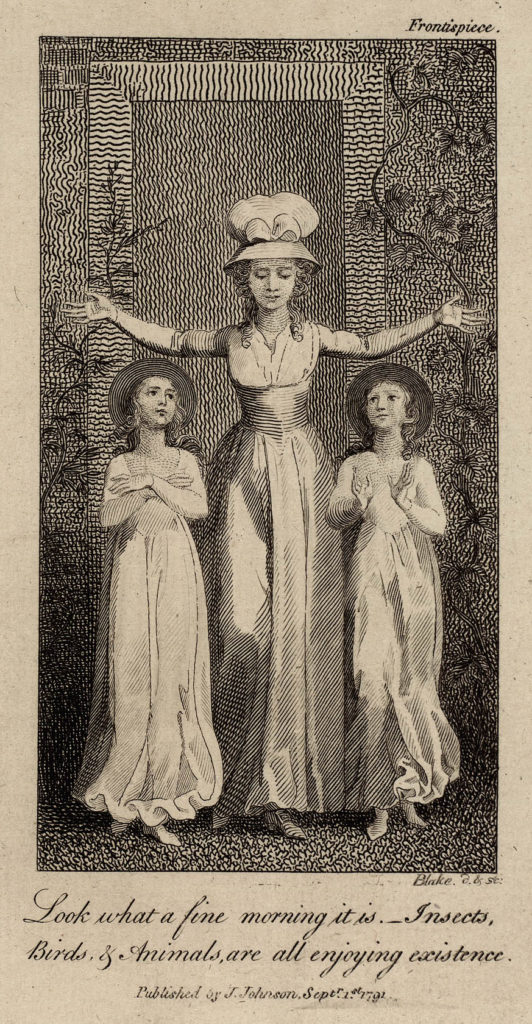

Mary Wollstonecraft, Original Stories from Real Life, Illustrated by William Blake

Women’s Legal Landmarks

Women’s Legal Landmarks, ed Erica Rackley and Rosemary Auchmuty, Hart Publishing, 2018, ISBN 978-1-78225-977-0, reviewed by Angela Ellis-Jones

This collection of short articles by mainly female authors marks the centenary of 1919, the year which saw the entry of women into the legal profession. Each chapter covers a ‘landmark’, a significant event in legal history as it affected women. The format for each chapter is four sections on Context, The Landmark, What Happened Next, and Significance. The landmarks are drawn from the four nations of the United Kingdom. The first chapter deals with the laws of the Welsh King Hywel Dda (early tenth century). Hywel codified the laws of Wales, which dealt with crime, property, tort, contract and the position of women: ‘Whilst they did not provide equality, the laws are noted and recognised for their enlightened attitude to women’ (26) – far more so than in many other European countries at the time, including England. The next landmark is Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), the fons et origo of the modern feminist movement, which called for equality and the extension of civil and political rights to women. The nineteenth century saw one of the most important of these rights extended, the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 (covered here), which enabled a married woman to hold all the property brought by her to the marriage or subsequently acquired as her ‘separate property’.

The great majority of these legal landmarks covered occurred in the twentieth century. They include pieces of legislation e.g. The Representation of the People Act 1918, which enfranchised women over 30, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, which enabled women to enter the professions and public functions, and events e.g. the Dagenham Car Plant Strike 1968, when women won a pay rise which led to the passing of the Equal Pay Act 1970.

Several chapters deal with the first woman to occupy an important position – e.g. Frances Moran, the first woman law professor in the British isles, who was appointed at TCD in 1925. The first woman law professor at a UK university (Public Law at Queen’s University, Belfast), Claire Palley, was not appointed until 1970. Unfortunately, the chapter on Palley does not say who the first woman Law professor at an English university was; there are now numerous such ladies. Several chapters are devoted to women such as the first woman solicitor in England and Wales (Carrie Morrison, 1922), the first woman to be admitted to an Inn of Court (Helena Normanton, 1919) the first woman to hold regular judicial office in England and Wales (Rose Heilbron,1964) – Normanton and Heilbron were the first women KCs, appointed in 1949 – the first woman High Court Judge in England and Wales (Elizabeth Lane (1965), the first woman appointed to the Court of Appeal (Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, 1988) and the first woman President of the Supreme Court (Brenda Hale, 2017)

Several other chapters deal with women’s property rights – the Married Women (Restraint upon Anticipation) Act 1949, the Married Women’s Property Act 1964, which enabled a married woman to share housekeeping money (and any property derived from that money) equally with her husband, when previously it was considered to be his only and so reverted back to him, and Williams and Glyn’s Bank v Boland (1980), in which the House of Lords endorsed the view of Lord Denning in the Court of Appeal (for once!) that wives could have overriding equitable interests in the matrimonial home that bound third parties. This led to mortgage lenders and conveyancers insisting that homes be conveyed to both spouses – a massive advance for women.

Many of the chapters are written with commendable objectivity, and provide a wealth of interesting information. Others, especially those dealing with women and reproduction, show a clear left-wing bias. Perhaps the worst is that dealing with Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Health Authority (1983), in which mother-of-ten Victoria Gillick sought a declaration against the DHSS that a government circular, originally issued by the 1974 Labour government, which allowed for confidential contraceptive advice and treatment to be available to those under 16 without parental consent, infringed her rights as a parent. She also sought a declaration against her local health authority that no-one employed by them could provide such advice and treatment to any of her under-16 daughters without her consent. Gillick lost in the High Court, won unanimously in the Court of Appeal, and lost 3/2 in the House of Lords.

The author of the article hails the judgment as ‘an important step towards the recognition of women’s sexual autonomy and freedom not only to engage in sexual activity, but also to be supported by the state to exercise control over their fertility confidentially, including those below the age of 16’. It has evidently escaped the author that a female under 16 is not a woman, and that this case effectively sanctioned the practice of ‘children having children’. Ironically, because it was about contraception it certainly gave support to an increasingly permissive moral climate in which recreational sex was seen as some sort of human right, with the consequent explosion in the rate of teenage pregnancy and illegitimacy. However, Gillick could also be presented as the first case pursued by a woman all the way to the country’s highest tribunal on an important moral/political issue: this point was not made in the article. There has not been a similar case until Gina Miller’s constitutional law litigation, following the 2016 referendum.

Other evidence of left-wing bias is that Margaret Thatcher was seen as too ‘controversial’ to include. Given that she was one of the first women to practise at the Tax Bar, as well as the first female to occupy the highest political office in the UK, this is a strange omission. In contrast, the left-wing Mary Robinson, the first woman President of Ireland, is given a chapter, although admittedly she was also a distinguished lawyer, having been appointed Professor of Law at TCD at the age of 25, and a campaigner for women’s rights.

The essays are generally written to a high standard of accuracy, with one exception. In the chapter on the Life Peerages Act 1958, Supuni Perera writes that ‘In 1953, Viscount Simon introduced a Bill to create up to 10 life peers of both sexes. Again the Bill failed this time because the Labour Government was ambivalent about the creation of new peerages in light of its desire to push for more comprehensive reform of the House of Lords’ (251). Yet the government from 1951, and for the rest of the 1950s, was Conservative!

Despite the left-wing bias of some of the chapters, I highly recommend this book. No reader can fail to be shocked at the injustice which so many women suffered, within living memory, from unequal legal provisions.

Angela Ellis-Jones is a writer and researcher, with an abiding interest in the law

Like this:

Like Loading...

Women’s Legal Landmarks

Mary Wollstonecraft, Original Stories from Real Life, Illustrated by William Blake

Women’s Legal Landmarks

Women’s Legal Landmarks, ed Erica Rackley and Rosemary Auchmuty, Hart Publishing, 2018, ISBN 978-1-78225-977-0, reviewed by Angela Ellis-Jones

This collection of short articles by mainly female authors marks the centenary of 1919, the year which saw the entry of women into the legal profession. Each chapter covers a ‘landmark’, a significant event in legal history as it affected women. The format for each chapter is four sections on Context, The Landmark, What Happened Next, and Significance. The landmarks are drawn from the four nations of the United Kingdom. The first chapter deals with the laws of the Welsh King Hywel Dda (early tenth century). Hywel codified the laws of Wales, which dealt with crime, property, tort, contract and the position of women: ‘Whilst they did not provide equality, the laws are noted and recognised for their enlightened attitude to women’ (26) – far more so than in many other European countries at the time, including England. The next landmark is Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Women (1792), the fons et origo of the modern feminist movement, which called for equality and the extension of civil and political rights to women. The nineteenth century saw one of the most important of these rights extended, the Married Women’s Property Act 1882 (covered here), which enabled a married woman to hold all the property brought by her to the marriage or subsequently acquired as her ‘separate property’.

The great majority of these legal landmarks covered occurred in the twentieth century. They include pieces of legislation e.g. The Representation of the People Act 1918, which enfranchised women over 30, the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act 1919, which enabled women to enter the professions and public functions, and events e.g. the Dagenham Car Plant Strike 1968, when women won a pay rise which led to the passing of the Equal Pay Act 1970.

Several chapters deal with the first woman to occupy an important position – e.g. Frances Moran, the first woman law professor in the British isles, who was appointed at TCD in 1925. The first woman law professor at a UK university (Public Law at Queen’s University, Belfast), Claire Palley, was not appointed until 1970. Unfortunately, the chapter on Palley does not say who the first woman Law professor at an English university was; there are now numerous such ladies. Several chapters are devoted to women such as the first woman solicitor in England and Wales (Carrie Morrison, 1922), the first woman to be admitted to an Inn of Court (Helena Normanton, 1919) the first woman to hold regular judicial office in England and Wales (Rose Heilbron,1964) – Normanton and Heilbron were the first women KCs, appointed in 1949 – the first woman High Court Judge in England and Wales (Elizabeth Lane (1965), the first woman appointed to the Court of Appeal (Elizabeth Butler-Sloss, 1988) and the first woman President of the Supreme Court (Brenda Hale, 2017)

Several other chapters deal with women’s property rights – the Married Women (Restraint upon Anticipation) Act 1949, the Married Women’s Property Act 1964, which enabled a married woman to share housekeeping money (and any property derived from that money) equally with her husband, when previously it was considered to be his only and so reverted back to him, and Williams and Glyn’s Bank v Boland (1980), in which the House of Lords endorsed the view of Lord Denning in the Court of Appeal (for once!) that wives could have overriding equitable interests in the matrimonial home that bound third parties. This led to mortgage lenders and conveyancers insisting that homes be conveyed to both spouses – a massive advance for women.

Many of the chapters are written with commendable objectivity, and provide a wealth of interesting information. Others, especially those dealing with women and reproduction, show a clear left-wing bias. Perhaps the worst is that dealing with Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbech Health Authority (1983), in which mother-of-ten Victoria Gillick sought a declaration against the DHSS that a government circular, originally issued by the 1974 Labour government, which allowed for confidential contraceptive advice and treatment to be available to those under 16 without parental consent, infringed her rights as a parent. She also sought a declaration against her local health authority that no-one employed by them could provide such advice and treatment to any of her under-16 daughters without her consent. Gillick lost in the High Court, won unanimously in the Court of Appeal, and lost 3/2 in the House of Lords.

The author of the article hails the judgment as ‘an important step towards the recognition of women’s sexual autonomy and freedom not only to engage in sexual activity, but also to be supported by the state to exercise control over their fertility confidentially, including those below the age of 16’. It has evidently escaped the author that a female under 16 is not a woman, and that this case effectively sanctioned the practice of ‘children having children’. Ironically, because it was about contraception it certainly gave support to an increasingly permissive moral climate in which recreational sex was seen as some sort of human right, with the consequent explosion in the rate of teenage pregnancy and illegitimacy. However, Gillick could also be presented as the first case pursued by a woman all the way to the country’s highest tribunal on an important moral/political issue: this point was not made in the article. There has not been a similar case until Gina Miller’s constitutional law litigation, following the 2016 referendum.

Other evidence of left-wing bias is that Margaret Thatcher was seen as too ‘controversial’ to include. Given that she was one of the first women to practise at the Tax Bar, as well as the first female to occupy the highest political office in the UK, this is a strange omission. In contrast, the left-wing Mary Robinson, the first woman President of Ireland, is given a chapter, although admittedly she was also a distinguished lawyer, having been appointed Professor of Law at TCD at the age of 25, and a campaigner for women’s rights.

The essays are generally written to a high standard of accuracy, with one exception. In the chapter on the Life Peerages Act 1958, Supuni Perera writes that ‘In 1953, Viscount Simon introduced a Bill to create up to 10 life peers of both sexes. Again the Bill failed this time because the Labour Government was ambivalent about the creation of new peerages in light of its desire to push for more comprehensive reform of the House of Lords’ (251). Yet the government from 1951, and for the rest of the 1950s, was Conservative!

Despite the left-wing bias of some of the chapters, I highly recommend this book. No reader can fail to be shocked at the injustice which so many women suffered, within living memory, from unequal legal provisions.

Angela Ellis-Jones is a writer and researcher, with an abiding interest in the law

Share this:

Like this: