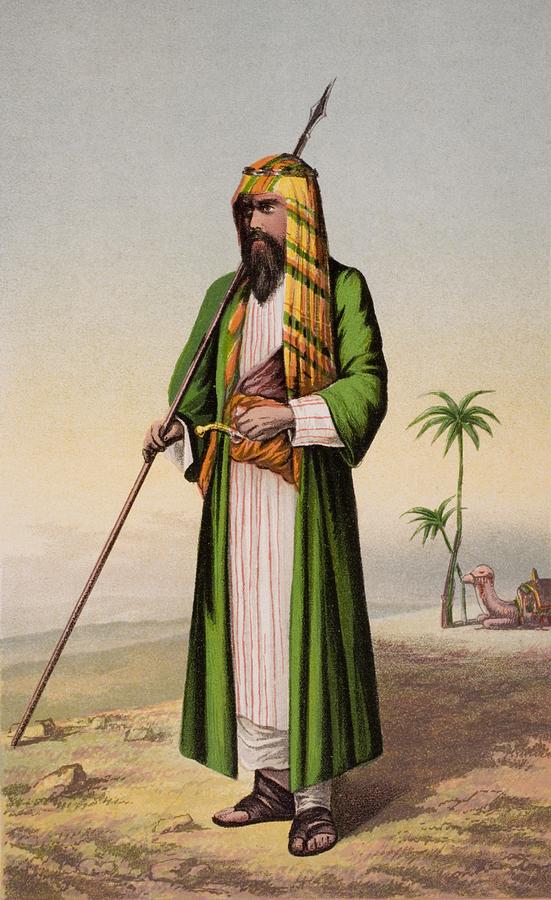

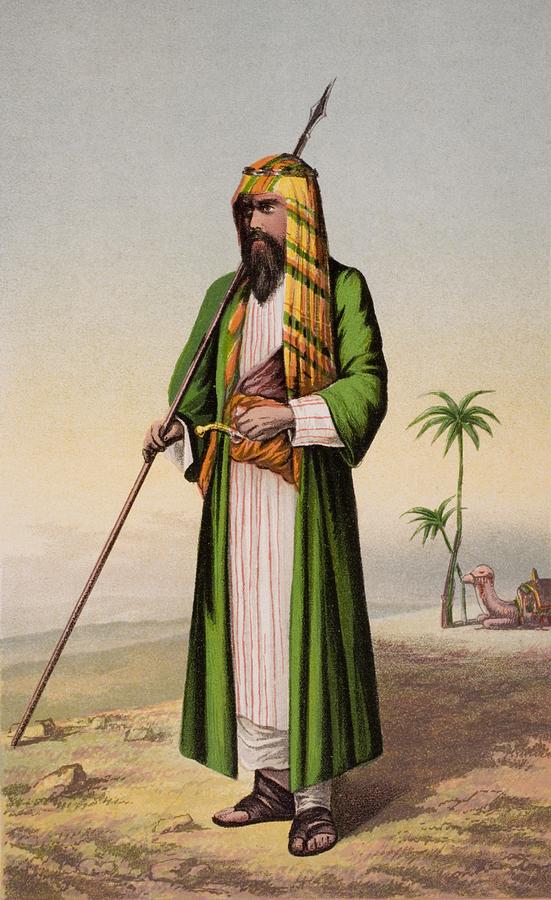

Richard Burton in Arabic attire, credit Wikipedia

Speke for England

River of the Gods: Genius, Courage, and Betrayal in the Search for the Source of the Nile, Candice Millard, Swift Books, 2023, pp349, reviewed by William Hartley

Two Victorian explorers risking their lives and wrecking their health in search of geography’s Holy Grail. If that wasn’t challenging enough, then add the fact that they were incompatible and knew it. This was the situation when Sir Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke set out to find the source of the Nile.

Burton has been well served by biographers (at least a dozen). He was a man of striking appearance and author Candice Millard raises the possibility that Bram Stoker used him as the model for Dracula. In contrast, Speke has vanished into obscurity. There is a third party in the story and posterity has been done a service by Millard in shining a spotlight upon him. It’s appropriate that he too should appear on the book’s cover, since in telling us some of his story, she has reminded readers that these Victorian feats of exploration couldn’t have taken place without the army of anonymous bearers and guides who accompanied them.

The two men had ventured into Africa before, originally in Somalia. It should have been sufficient warning that they were not compatible; Speke seems to have felt that he was better equipped to be in charge. For his part, Burton was disdainful of the other man’s lack of interest in the people and cultures they encountered. It all went horribly wrong. During a fight with tribesmen on a beach near Berbera in 1855, Burton took a spear through the face from cheek to cheek. Somehow doctors and dentists patched up the wreckage. Not to be left out, Speke picked up eleven stab wounds.

River of the Gods concentrates on the relationship between the two men, dominated as it was by the search for the source of the Nile. The author has brought Speke out of Burton’s shadow, revealing someone who bore grudges and resented the older man’s fame and charisma. Striking a balance between the two must have been difficult since Burton has much more to offer a biographer. He was an ethnographer, a polyglot who spoke at least twenty five languages and could so assimilate himself into an alien culture that he entered Mecca posing as a pilgrim. Speke preferred slaughtering the local wildlife.

As others more amenable became unavailable, Burton was forced to recruit Speke for the second expedition, in order to utilise his map making skills. The Royal Geographical Society, which was sponsoring the expedition, would of course need evidence that they had discovered the source of the Nile. The man who held the expedition together as the two were incapacitated by illness was Sidi Mubarak Bombay. Born in Africa, he was seized by slavers and taken to India. He never saw his parents again and even his real name was lost. There was a slight advantage of being the victim of East African slavery. Following the death of his master, Bombay was automatically released from servitude and after military service returned to Africa. Thanks to this book he now receives his rightful place in the history of African exploration. Bombay emerges as the man who helped maintain morale: endlessly encouraging and cheerful, whilst Burton and Speke were stricken with awful diseases. Not much is known about the man but Millard has done the best she could with the available material, in this fast paced account. Subsequently, he went on to guide Stanley in his search for Dr. Livingstone and was among those to make the first successful crossing of the continent.

Burton was too ill to make the trip to the lake which Speke claimed as the source of the Nile. Instead he insisted on the lake he did see as the source. Geographers will of course point out that it depends on what you mean by the word source. Despite being the man who got there, Speke found himself overshadowed by the man who didn’t. Following the discovery of the source of the Nile the rest of the book might easily have been an anti climax. This doesn’t happen; in part because a fourth personality comes into view. Isobel Arundel had hero worshipped Burton for many years and defied her family by going on to marry him. She was a devout Catholic and a loyal wife, who stayed with him during the various consular appointments which kept him occupied (after a fashion) for the rest of his life.

Part of Speke’s problem was an inability to record his achievements in effective and coherent prose. As the author says, Speke had an astonishing story to tell but just didn’t know how to tell it. Then came the proposed showdown: a debate between the two most famous explorers of the age, each defending their view about the source of the Nile. Millard does a good job of describing the complexity of the question, plus the involvement of Burton’s wife and her hope that the two men might be reconciled. But it was an unequal contest. Burton was an electrifying speaker and a formidable opponent in debate but the confrontation was not to take place, due to Speke’s untimely death. Speke died as a result of a gunshot wound. Could it have been an accident? Perhaps, but he was renowned for the care he took when handling firearms.

The explorations which made Burton famous were over but he continued to write. His translations were to earn him much needed money, though they scandalised Victorian society. The Arabian Nights brought in 16, 000 guineas. Writing in the Edinburgh Review, Henry Reeve ensured its success by saying ‘It is a work which no decent gentleman will long permit to stand on his shelves’. Following his death, Burton’s widow, anxious to preserve his reputation, carried out one of the greatest acts of literary vandalism in the nineteenth century by destroying one of his translations.

For anyone keen to learn about the life of Burton, there are plenty of sources. What Millard does is show the reader how interlinked these two opposites became. In doing so she has given Speke a significance that he has lost down the years. An excellent book for those interested in Victorian era exploration, adventure and scholarship.

William Hartley is a Social Historian

Like this:

Like Loading...

Was Burton a homosexual masochist like Lawrence?

Just asking.