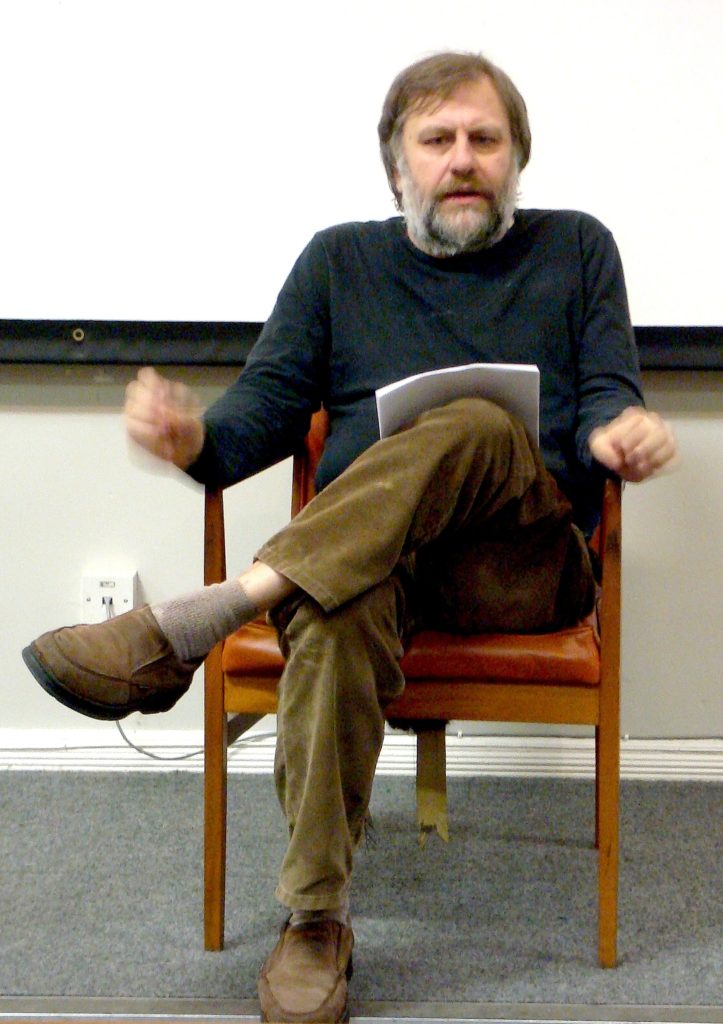

Slavoj Žižek – visionary of violence

HENRY HOPWOOD-PHILLIPS examines one of today’s most lionized Leftists

Slavoj Zeek

Born in 1949 to an economist and an accountant in Ljubljana, Slovenia, Slavoj Žižek is a cultural critic renowned for his innovative interpretations of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. Žižek is quite possibly the closest thing the 21st century has to a living philosopher. Although an academic at several universities (including Ljubljana, Columbia, Princeton, New York and Michigan) the professor is far from fusty.

The Slovenian’s work is full of humour and contains a blatant disregard for the distinctions conventionally made between high and low forms of culture. Terry Eagleton’s description perhaps hits on the professor’s unique qualities:

“There are two jokes in particular that are, so to speak, on the Žižekian reader. The first…Žižek looks like a fun read, and in many respects is so; but he is also an exceptionally strenuous thinker reared in the high traditions of European philosophy. The second is that Žižek is not a postmodernist at all. In fact, he is virulently hostile to that whole current of thought… If he steals some of the postmodernists’ clothes, he has little but contempt for their multiculturalism, anti-universalism, theoretical dandyism and modish obsession with culture.”

Žižek steals postmodern clothes, including, if one wanted to be cruel, postmodern language – academese. Make no bones about it – it is often hard work deciphering him. However, his work can be summarised as an extended critique of the West’s current liberal and globalist ideology, which is so embedded in our consciousness that it has become almost second nature. The ideology has in fact become the system. He says,

“Ideology is strong exactly because it is no longer experienced as ideology…we feel free because we lack the very language to articulate our unfreedom.”

Žižek reminds us that in an age when we are encouraged to believe we are freer than any other,

“[M]adness is not only the beggar believing himself to be a King. He is the King who really believes himself to be a King.”

The current ideology is remarkably successful because it sells itself as an anti-ideology, in the same way a folk singer might adopt an anti-capitalist avatar to fulfill a market niche. It proposes no concrete positive project but rather its logic slowly shuts down the alternatives. The body politic facilitates this process by resisting political ‘extremes’, encouraging managerialism, and adopting a victimist narrative that cushions actors from their actions, arrests responsibility and incentivises stability. All values which are not already embedded in the system’s logic are dismissed alternately as quixotic or millenarian, naive or futile. Even its most serious historical opposition, Marxism, has been neutered. In such circumstances Žižek laments how the left has been “caught with its pants down”, failing to offer either a genuine alternative or even a proper critique. Even investigative journalism of a leftist bent rarely offers anything more adventurous than a “bourgeois heroism”: exposing inefficient practices such as corruption or criticising disproportionate rewards. Politics barely survives this political vacuum. It is reduced to the residue that remains when values are subtracted from life, its highest end relegated to little more than the coordination of interests.

Žižek violently disagrees with this therapeutic belief-system. In this post-political age, he argues that we are “desubjectivized” in the name of liberation without being offered new values or foci for allegiance. This is the plea of many who are grasping for an identity in a market place which offers rootless, disposable, superficial and flattened modes of being.

The global order is sustained less by explicit censorship than by restriction of scope. It is not what is proscribed but what is not acknowledged that matters. Immigration is a brilliant example. Žižek describes liberal multiculturalism as “barbarism with a human face”. Authentic difference is translated through a series of legal fictions into matters of sterile indifference. Prohibition is prohibited so that actual otherness is either illegal or personalised to the point of public irrelevance so that, with a paradoxical brilliance, the more tolerant a society becomes the more homogenous it becomes. Anxiety, identity and boredom replace fortitude, pride and being. “Respect” and “difference” become articles of faith, holy particulars forming misguided substitutes for the ideas of commonality that used to constitute the locus for Man’s liberation.

The global order is dependent on capitalism, which is now fleeing from its earlier liberalizing manifestations. International capital undermines national democracy and it is the latter which is jettisoned – as we are presently witnessing in Greece. Peoples, once valued as peoples using the market to fulfil themselves, are reduced to components used by markets to fulfil capabilities.

Yet the market is inherently unbalanced. Like a car spinning its wheels in a ditch, we remain stuck in “turbo paralysis” (1): a permanent emergency mode. The ruling classes have drifted from being direct owners of capital to being its detached managers who ‘do time’ for companies that can provide dividends to shareholders almost on autopilot, in return for astronomic remuneration irrespective of their performance.

Meanwhile the lower-middle classes are being re-proletarianised as their skills are rendered un-monetisable or replaced by machinery. The middle classes are becoming an anachronism, necessary to early and middle stage capitalism but increasingly irrelevant in its advanced forms. The future, says Žižek, is Dubai “where the other side are literally slaves”. Žižek is being flippant, but he hits on the point that the midde there is neither large nor organic, but rather an extension downwards of elites, like a court, rather than upwards of workers, as in orthodox models for economic advancement.

The welfare state has, accordingly, moved from being a safety net to a device that purchases the acquiescence of the unemployed. But this model is based on political calculation, not love or national fraternity. As technology races and income inequality soars, political reasoning may change. South Africa and its gated apartheid are more likely an indication of the future than the UK and its welfare state.

These profound changes in our system are being addressed in a woefully inadequate manner. Myopic managerialism has consistently and cynically addressed consequences instead of causes, and the bigger picture has been lost.

According to Žižek, when ideology “oppresses” in this manner, violent rebellion becomes nothing short of a moral duty. Although Žižek would doubtless dislike the comparison, such resistance to ideological weight lies at the heart of every fascist or jihadist. All wish, not for their own patch under the sun, but a new sun altogether. Indeed, some mainstream commentators have speculated that Žižek seems to desire a “perfected” non-racist form of fascism.

Žižek uses (or misuses) Hegel to justify this rebellion (2). He acknowledges that violence may be painful and dangerous but claims that it is also a duty to participate in the dialectic. Chaos and hope are held up as preferable to stability and despair. This revolutionary defeatist philosophy was best encapsulated by Mao: “There is disorder under heaven, and the situation is excellent”.

In any case, Žižek feels that violence perpetuates the system as much as it violates it. From law to foreign policy, ideology arbitrarily validates violence according to its own agenda. It is important to remember with Žižek that his conceptions of violence rarely promote the physical variety. For him, Gandhi was a true radical, because with little physical violence and great mental exertion, he completely replaced one system with another.

The Slovenian believes that violence has a redemptive power, a cathartic core. He demands that violence be acknowledged as capable of containing a kind of “goodness… able to injure – to injure savagery” (Brecht) – a violence not aimed at people as people but rather people as instruments. Such a rationale will sound tragically familiar to those familiar with 20th century history.

Žižek is fond of a modern rendering of St Paul’s quote in Ephesians 6:12:

“Our struggle is not against concrete, corrupted individuals, but against those in power in general, against their authority, against their global order and the theological mystification that sustains it”. (3)

Whether you agree with his analysis or not, Žižek opens your eyes to “an old world… dying, and [a] new struggl[ing] to be born”, a reluctant recognition that “now is the time of monsters” (4).

HENRY HOPWOOD-PHILLIPS works in publishing in London

NOTES

1. Mark Lind, Spectator, Christmas 2012

2. For example, “I adhere to the view that the world spirit has given the age marching orders. These orders are being obeyed. The world spirit, this essential, proceeds irresistibly like a closely drawn armored phalanx advancing with imperceptible movement, much as the sun through thick and thin. Innumerable light troops flank it on all sides, throwing themselves into the balance for or against its progress, though most of them are entirely ignorant of what is at stake and merely take head blows as from an invisible hand.” (Hegel writing to Niethammer, 5 July 1816). In reality, Hegel was strongly against violence

3. The King James original is “For we wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places”

4. Gramsci, Selections from Prison Notebooks, 1971