Cannibal Lecture

Ilana Mercer on reparations

Apartheid and the Atlantic slave trade have generated an endless, media-generated pretense of remorse, especially in America and Great Britain. Spectacle aside, the real motive is to define, and therefore control, the past by reading it as an aspect of present political aims. “[R]itual apologies,” argues Jeremy Black, author of “The Slave Trade,” “are moves in a political game that relies on “fatuous arguments about ‘closure’ [and] ‘resolution,’” but fails to reach closure, since the purpose of such policies is to keep the imagined wounds suppurating.

Plainly put, racial-grievance politics are levelled, in general, by Africans who were never enslaved or who were not born into apartheid, against Europeans who did not enslave or segregate them. Only in the West could such a vicarious cult of self-flagellation thrive. As I wrote in my book, Into the Cannibal’s Pot: Lessons for America From Post-Apartheid South Africa, “White South Africans are told to give up ancestral lands they are alleged to have stolen. Should not the relatives of cannibals who gobbled up their black brethren be held to the same standards?”

Part of the problem is our ignorance of Southern African history. There was bitter blood on Bantu lands well before white settlers arrived. The Bantu were not indigenous to South Africa. They migrated there out of central Africa and, like the European settlers, used their military might to displace Hottentots, Bushmen and one another through internecine warfare.

The San people of Southern Africa, or “Bushmen,” are renowned for their unequalled tracking skills and for their delicate drawings on rock outcroppings. The San were hunters, but they were also among the hunted. Mercilessly so. As late as the early 20th century, the Boers, Hottentots, and Bantu made frequent sport of tracking and killing the San.

In “The Washing of the Spears: The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation,” historian Donald R. Morris notes that Cape Town’s founder and Dutch East India Company official J. A. Van Riebeeck landed at the Cape in 1652, 500 miles to the south and 1,000 miles to the west of the nearest Bantu. Joined by other Protestants from Europe, Dutch farmers, as we know, homesteaded the Cape Colony.

Doubtless, the question of land ownership deeply concerned the 19th century trek Boers, as they decamped from the British-ruled Cape Colony and ventured north. Accordingly, they sent out exploration parties tasked with negotiating the purchase of land from the black chieftains, who often acted magnanimously, allowing Europeans to settle certain areas. Trek Boers, it must be said, were as rough as the natives and negotiated with as much finesse. Still, the received narrative about the pastoral, indigenous, semi-nomadic natives, dispossessed of their lands in the 17th century, is as simplistic as it is sentimental.

When Boer and Bantu finally clashed on South Africa’s Great Fish River it was a clash of civilizations. The Bantu regarded their traditional lands as clan possessions in perpetuity. A chieftain could grant temporary rights, but could not permanently alienate the land. The European mind in general could not grasp the concept of collective ownership and thought of land purchases as part of a binding contract on the individuals involved. As Morris observes in his matter-of-fact way, “The Bantu view insured European encroachment and the European view insured future strife.”

South Africa has since reverted to the “Bantu view.” It is perhaps inevitable that 21st-century claims for “restitution” in South Africa are not dominated by individual freehold owners reclaiming expropriated land on the basis of title deeds kept on record. Rather, a group of blacks scheming on a property will band together as a “tribe,” pooling the taxpayer grants which its members have received gratis, for the purpose of purchasing occupied land. No sooner does this newly constituted “tribe” launch a claim with the South African Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, than related squatters—sometimes in the thousands—move to colonize the land. They defile its grounds and groundwater by using these as one vast latrine, and terrorize, even kill, its occupants and their livestock in the hope of “nudging” them off the land.

Back in the day, Shaka Zulu himself considered the European clansmen to be the proper proprietors of the Cape frontier, with whom he would need to liaise diplomatically if he wished to subjugate his black brethren, the Xhosa-Nguni peoples, on the southern reaches of his empire, abutting the Cape. The white civilization which formed south of the Orange River did not encounter the black civilization in the interior for some time. But during that time, the black coastal clans warred against one another, continually raiding other kraals, driving off the cattle and exterminating the victims.

Before the consolidation of the Zulu empire, some eight hundred Nguni Bantu clans vied for a place in the sun in the Natal region between the mountains and the coast. Where are these lineages today? The period from 1815 – 1840, known as the Mfecane, “the Crushing,” was particularly brutal. Up to two million natives died, depopulating what is today the Orange Free State. This death toll was not entirely the fault of Shaka. Other causes included rising populations and vicious competition for land among tribal groups. Nonetheless, Shaka—who once dissected 700 pregnant women—destroyed the clan structure in Natal.

As I observed in Into the Cannibal’s Pot, during the mass migration caused by tribal warfare, “not a single clan remained in a belt a hundred miles wide south of the Tugela River; in an area that teemed with bustling clans only thousands of deserted kraals remained, most of them in ashes.” A few thousand terrified inhabitants found refuge in the bush or forest in pitiful bands, while cannibalism ran rampant, as it did whenever the kraaleconomy was demolished in ongoing warfare.

Lest one imagine that cannibalism was a common practice at the time, it “was fully repugnant to Bantu civilization as it is to our own, [but a point was reached] … where entire clans depended on it to feed themselves.” Mobs on the move marked their aimless tracks with (DNA-rich) human bones. Was there never a duty to employ these bones for purposes other than soothsaying—say, to do the devoured justice?

To repeat: should not the descendants of cannibals who gobbled up their black brethren be petitioned for reparations? Don’t the descendants of Shaka Zulu owe reparation to the remnants of the Nguni Bantu clans they hounded in the course of consolidating the Zulu Empire? The Bushmen are, indubitably, the first nations of Southern Africa. These long-suffering people have been barred by the Botswana Bantu from claiming their ancestral lands in the Central Kalahari. But where’s the international uproar?

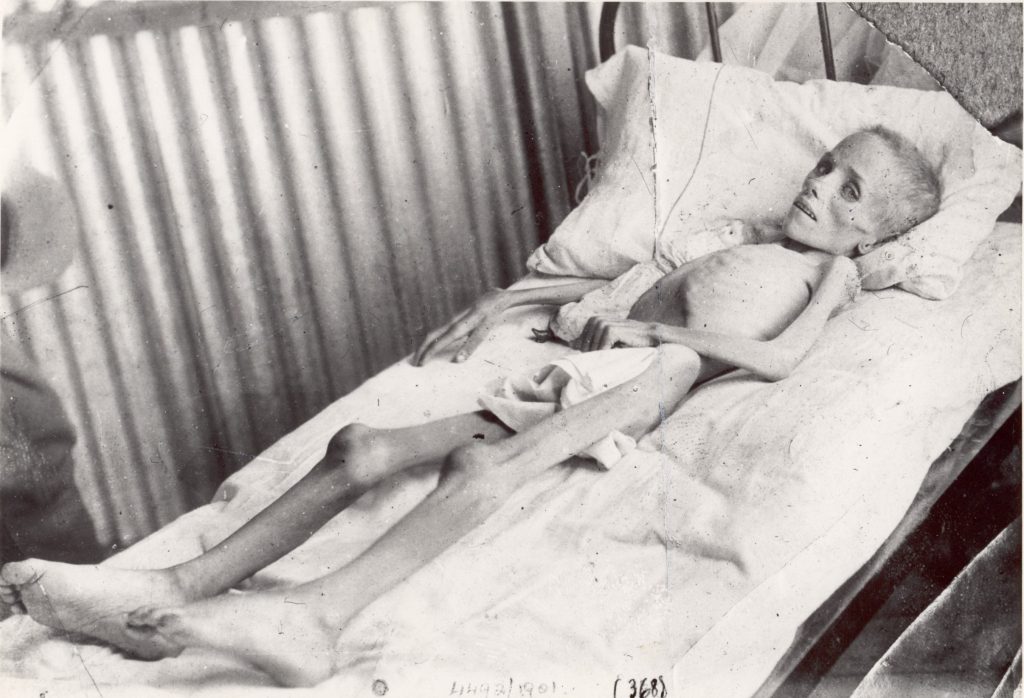

How about requiring Gangland Chicago, a generational enterprise, to pay reparations to victims and their families? But charity begins at home. In the Boer War (1899-1902), the British established concentration camps in which approximately 26,000 Afrikaners, mostly women and children, perished. Surviving photographs from the camps bring to mind starving Jewish victims of Nazi atrocities. So, don’t the British authorities owe reparations to the relatives of, say, little Lizzie van Zyl, who perished in a Bloemfontein camp set up by the British for her people? Intra-racial reparations are my modest proposal to counter the Democrats’ relentless, reparations drumbeat.

Lizzie van Zyl

Editorial note; part 1 of this article was published on June 11th 2019

Ilana Mercer has been writing a weekly, paleolibertarian column since 1999. She’s the author of Into the Cannibal’s Pot: Lessons for America From Post-Apartheid South Africa (2011) & The Trump Revolution: The Donald’s Creative Destruction Deconstructed” (June, 2016). She’s on Twitter, Facebook & Gab. Latest on YouTube

Like this:

Like Loading...

Cannibal Lecture

Cannibal Lecture

Ilana Mercer on reparations

Apartheid and the Atlantic slave trade have generated an endless, media-generated pretense of remorse, especially in America and Great Britain. Spectacle aside, the real motive is to define, and therefore control, the past by reading it as an aspect of present political aims. “[R]itual apologies,” argues Jeremy Black, author of “The Slave Trade,” “are moves in a political game that relies on “fatuous arguments about ‘closure’ [and] ‘resolution,’” but fails to reach closure, since the purpose of such policies is to keep the imagined wounds suppurating.

Plainly put, racial-grievance politics are levelled, in general, by Africans who were never enslaved or who were not born into apartheid, against Europeans who did not enslave or segregate them. Only in the West could such a vicarious cult of self-flagellation thrive. As I wrote in my book, Into the Cannibal’s Pot: Lessons for America From Post-Apartheid South Africa, “White South Africans are told to give up ancestral lands they are alleged to have stolen. Should not the relatives of cannibals who gobbled up their black brethren be held to the same standards?”

Part of the problem is our ignorance of Southern African history. There was bitter blood on Bantu lands well before white settlers arrived. The Bantu were not indigenous to South Africa. They migrated there out of central Africa and, like the European settlers, used their military might to displace Hottentots, Bushmen and one another through internecine warfare.

The San people of Southern Africa, or “Bushmen,” are renowned for their unequalled tracking skills and for their delicate drawings on rock outcroppings. The San were hunters, but they were also among the hunted. Mercilessly so. As late as the early 20th century, the Boers, Hottentots, and Bantu made frequent sport of tracking and killing the San.

In “The Washing of the Spears: The Rise and Fall of the Zulu Nation,” historian Donald R. Morris notes that Cape Town’s founder and Dutch East India Company official J. A. Van Riebeeck landed at the Cape in 1652, 500 miles to the south and 1,000 miles to the west of the nearest Bantu. Joined by other Protestants from Europe, Dutch farmers, as we know, homesteaded the Cape Colony.

Doubtless, the question of land ownership deeply concerned the 19th century trek Boers, as they decamped from the British-ruled Cape Colony and ventured north. Accordingly, they sent out exploration parties tasked with negotiating the purchase of land from the black chieftains, who often acted magnanimously, allowing Europeans to settle certain areas. Trek Boers, it must be said, were as rough as the natives and negotiated with as much finesse. Still, the received narrative about the pastoral, indigenous, semi-nomadic natives, dispossessed of their lands in the 17th century, is as simplistic as it is sentimental.

When Boer and Bantu finally clashed on South Africa’s Great Fish River it was a clash of civilizations. The Bantu regarded their traditional lands as clan possessions in perpetuity. A chieftain could grant temporary rights, but could not permanently alienate the land. The European mind in general could not grasp the concept of collective ownership and thought of land purchases as part of a binding contract on the individuals involved. As Morris observes in his matter-of-fact way, “The Bantu view insured European encroachment and the European view insured future strife.”

South Africa has since reverted to the “Bantu view.” It is perhaps inevitable that 21st-century claims for “restitution” in South Africa are not dominated by individual freehold owners reclaiming expropriated land on the basis of title deeds kept on record. Rather, a group of blacks scheming on a property will band together as a “tribe,” pooling the taxpayer grants which its members have received gratis, for the purpose of purchasing occupied land. No sooner does this newly constituted “tribe” launch a claim with the South African Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, than related squatters—sometimes in the thousands—move to colonize the land. They defile its grounds and groundwater by using these as one vast latrine, and terrorize, even kill, its occupants and their livestock in the hope of “nudging” them off the land.

Back in the day, Shaka Zulu himself considered the European clansmen to be the proper proprietors of the Cape frontier, with whom he would need to liaise diplomatically if he wished to subjugate his black brethren, the Xhosa-Nguni peoples, on the southern reaches of his empire, abutting the Cape. The white civilization which formed south of the Orange River did not encounter the black civilization in the interior for some time. But during that time, the black coastal clans warred against one another, continually raiding other kraals, driving off the cattle and exterminating the victims.

Before the consolidation of the Zulu empire, some eight hundred Nguni Bantu clans vied for a place in the sun in the Natal region between the mountains and the coast. Where are these lineages today? The period from 1815 – 1840, known as the Mfecane, “the Crushing,” was particularly brutal. Up to two million natives died, depopulating what is today the Orange Free State. This death toll was not entirely the fault of Shaka. Other causes included rising populations and vicious competition for land among tribal groups. Nonetheless, Shaka—who once dissected 700 pregnant women—destroyed the clan structure in Natal.

As I observed in Into the Cannibal’s Pot, during the mass migration caused by tribal warfare, “not a single clan remained in a belt a hundred miles wide south of the Tugela River; in an area that teemed with bustling clans only thousands of deserted kraals remained, most of them in ashes.” A few thousand terrified inhabitants found refuge in the bush or forest in pitiful bands, while cannibalism ran rampant, as it did whenever the kraaleconomy was demolished in ongoing warfare.

Lest one imagine that cannibalism was a common practice at the time, it “was fully repugnant to Bantu civilization as it is to our own, [but a point was reached] … where entire clans depended on it to feed themselves.” Mobs on the move marked their aimless tracks with (DNA-rich) human bones. Was there never a duty to employ these bones for purposes other than soothsaying—say, to do the devoured justice?

To repeat: should not the descendants of cannibals who gobbled up their black brethren be petitioned for reparations? Don’t the descendants of Shaka Zulu owe reparation to the remnants of the Nguni Bantu clans they hounded in the course of consolidating the Zulu Empire? The Bushmen are, indubitably, the first nations of Southern Africa. These long-suffering people have been barred by the Botswana Bantu from claiming their ancestral lands in the Central Kalahari. But where’s the international uproar?

How about requiring Gangland Chicago, a generational enterprise, to pay reparations to victims and their families? But charity begins at home. In the Boer War (1899-1902), the British established concentration camps in which approximately 26,000 Afrikaners, mostly women and children, perished. Surviving photographs from the camps bring to mind starving Jewish victims of Nazi atrocities. So, don’t the British authorities owe reparations to the relatives of, say, little Lizzie van Zyl, who perished in a Bloemfontein camp set up by the British for her people? Intra-racial reparations are my modest proposal to counter the Democrats’ relentless, reparations drumbeat.

Lizzie van Zyl

Editorial note; part 1 of this article was published on June 11th 2019

Ilana Mercer has been writing a weekly, paleolibertarian column since 1999. She’s the author of Into the Cannibal’s Pot: Lessons for America From Post-Apartheid South Africa (2011) & The Trump Revolution: The Donald’s Creative Destruction Deconstructed” (June, 2016). She’s on Twitter, Facebook & Gab. Latest on YouTube

Share this:

Like this: