Militarisation of the Left

The Red Brigades: The Terrorists Who Brought Italy to its Knees, 2025, Bloomsbury Publishing, London, Oxford etc, John Foot, hb, 450 pp, reviewed by Leslie Jones

“An oppressed class that does not strive to learn to use arms, to acquire arms only deserves to be treated like slaves”, V I Lenin

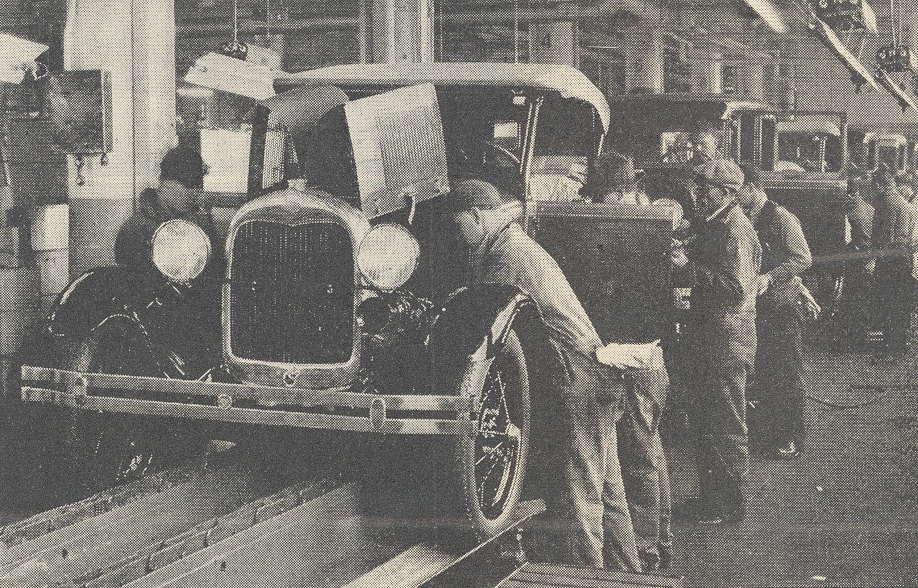

In 1970, the Red Brigades (Brigate Rosse) were established in Milan by Renato Curcio and Margherita Cagol, students at the Institute of Sociology in Trento. The BR had their roots in the student movements of 1967-8 and were inspired, accordingly, by the struggle against imperialism in Vietnam and by the Chinese and Cuban Revolutions. But political violence from the left, as Professor Foot makes clear, was also engendered by Fordism. Frederick Taylor, author of Principles of Scientific Management (1911), had envisaged “a perfect man-machine symbiosis”. He viewed workers as “predictable, machine-like objects” (see Broken Myths: Charles Sheeler’s Industrial Landscapes, Andrea Diederichs, De Gruyter (2023), reviewed in QR, January 2023, by Leslie Jones). Henry Ford, by his introduction of the assembly line, put Taylorism into practice à outrance. Workers were monitored and restricted to simple, repetitive, “mind numbing” tasks, “beneath the dignity of able-bodied men” according to sociologist Thorstein Veblen. The upshot was absenteeism and a high turnover of labour.

Fiat Mirafiori in Turin, the biggest factory in Italy, had 46,000 workers in 1967. It was run on “Fordist production lines, where discipline was key to profits”.[i] In 1969, Curcio and Cagol established links with militants in the huge Pirelli Biccoca rubber plant in Milan. Discontent with working conditions was rife. The 1968-9 strike wave in Italy took on some novel forms. Traditional trade unions and the Communist Party (PCI) were superseded. In Milan, unprecedented demands were made concerning housing and education. The CUB (Comitato Unitario di Base) brought together workers, students and political militants.

According to Professor Foot, the BR glossed over the differences between armed struggle against military dictatorships in the Third World and armed struggle against the contemporary Italian state. Its leaders were persuaded that the latter was only nominally democratic and irrevocably tainted by its associations with fascism, an idea they shared with the Baader-Meinhof group or Red Army Faction.[ii] Giovanni Pesce’s No Quarter (1967), a “1968ers Bible”, was a profound influence in this context. Pesce, a former member of the Resistance and a leading member of the GAP, had carried out violent attacks against the fascist state. But Foot debunks the idea that BR were the “heirs of Pesce’, since Italy was “a democracy with an anti-fascist constitution”[iii] Yet he acknowledges that neo-Fascists, in conjunction with the secret police, carried out the Piazza Fontana massacre in Milan in December 1969 which was falsely attributed to left wing groups. This, arguably, was part of a strategy of tension intended to blame the left for violence and restrict democracy.

State violence and lies were copiously documented in La Strage di Stato (State Massacre), 1970. Multimillionaire Giangiacomo Feltrinelli, the publisher of No Quarter, compared the Piazza Fontana bomb plot to the Reichstag fire of 1933. The result was that many Italians ceased to believe in the justice system. Foot concedes that Italy’s “corrupt and unloved state and political system” [iv] legitimised the BR. So did the return of repressive aspects of justice last seen under fascism, such as prisons on remote islands, and the use of torture. The BR’s tactic was to lay bare “the real – supposedly repressive – nature of the state” [v]

Feltrinelli financed armed groups on the left. He considered the Tupamaros, an armed left-wing urban guerilla movement active in Uruguay in the 1960’s, worthy of emulation. The IRA, ETA and the PLF were his other role models. According to such revolutionary luminaries as Regis Debray, Che Guevara and Fidel Castro, a small cadre of revolutionaries can provide the spark that ignites a revolution. This notion bespeaks Lenin’s concept of the vanguard of the proletariat and Marx’s notion of a vanguard political party. According to Foot, however, groups like the Tupamaros and BR “turned classic Marxism on its head” [vi]. He contends that this concept of an “elite of trained militants”, of “a tiny compact group” imbued with higher consciousness, rendered the masses not only “irrelevant” but also a “problem”. He strenuously rejects the claim of the BR to represent the proletariat, maintaining that most workers in Italy’s mega factories were at best indifferent to their sloganeering.

BR bank robberies (“proletarian appropriations” for their apologists) were for Foot “armed robberies”, pure and simple. He dismisses the idea that BR’s kidnaps, trials and “people’s prisons” constituted a proletarian form of justice. The collateral victims of BR actions are another of his recurrent themes. Justification of BR terror, such as killing journalists, on the ground that workers are also exploited and killed, is summarily dismissed as “whataboutery”[vii].

Foot’s arresting subtitle is The Terrorists who Brought Italy to Its Knees. In May 1972, Luigi Calabresi, head of Milan’s political police office at the time of the Piazza Fontana incident, was assassinated by Lotta Continua. Even when left-wing terrorists were brought to trial, their record of violence and seeming invincibility intimidated magistrates and lawyers and deterred potential jurors and witnesses, threatening for a time to undermine the judicial process. But however much the author deplores the “criminal violence” of BR, he acknowledges their uncanny capacity to manipulate the media. They were “the best-known armed group” on the left [viii] in the 70’s and 80’s. And concerning the kidnap of Genoa public prosecutor Mario Sossi, in April-May 1974, he concludes, “A tiny group of militants had captured the attention of Italy”[ix] The pièce de resistance, in this context, was the kidnap and execution of former prime minister Aldo Moro in Rome, March-May 1978.

The Red Brigades is painstakingly researched and a compelling read. The author skilfully guides us through a morass of conflicting conspiracy theories. But we were reminded of a sagacious comment made by sociologist Robert Michels, in Political Parties (1911):

Any class which has been enervated and led to despair…through prolonged lack of education and thorough deprivation of political rights, cannot attain to the possibility of energetic action until it has received instruction…from those who belong to…a “higher” class.

Red Brigades logo, credit Wikimedia Commons

Dr Leslie Jones is the Editor of Quarterly Review

ENDNOTES

[i] Foot, p36

[ii] See ‘Nazi officials ran German state for decades after war’

Oliver Moody, The Times, August 19th, 2025

[iii] Foot, p16

[iv] Foot, p173

[v] Foot, p194

[vi] Foot, p23

[vii]Foot, p50

[viii]Foot, p130

[ix] Foot, p112

A few “random thoughts of a fascist hyena”:

A personalities addicted to “extreme” politics change sides, sometimes through disillusion.

The organised Leninist Left will vary tactics according to situations, infiltrate agents provocateurs, manipulate media and rewrite history… See e.g. Eugene Methvin’s “The Riot Makers” (Arlington 197o).

Robert Michels is one of the now-neglected greats of political sociology.

Communists killed more people than fascists or colonialists.

Soviet propaganda claimed collusion between violent “ultra-rightists” and Maoists. See e.g. Ernst Henry, “Stop Terrorism” (Novosti 1982).

If there is hope, it probably doesn’t lie with the proles.

The world is disintegrating into basic urges of greed, lust and hate, all facilitated by modern technology. Who can get a grip? Not Trump, Xi, Putin, Starmer, Netanyahu, Modi….

And God is dead.