Classic QR – the original 1848 review of Vanity Fair

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article by “Elizabeth Rigby” (I am unsure whether this is a real person or just a nom de plume) appeared in the December 1848 edition of the Quarterly Review. It is an abridged extract from a combined review of Vanity Fair and Jane Eyre. The Jane Eyre segment was posted here previously. Derek Turner, 19 April 2012

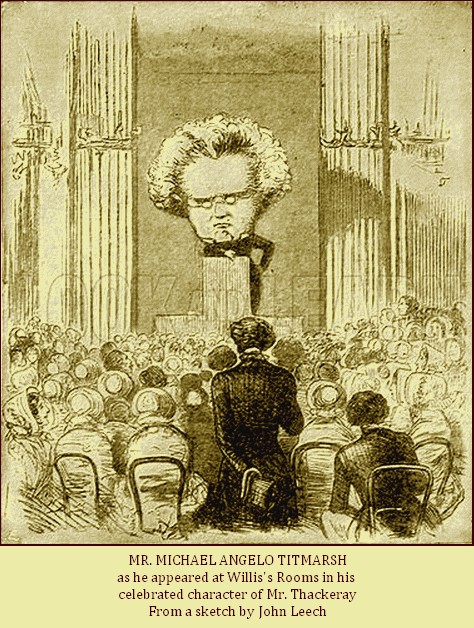

Mr Thackeray from a sketch by John Leech

We were perfectly aware that Mr. Thackeray had of old assumed the jester’s habit, in order the more unrestrainedly to indulge the privilege of speaking the truth – we had traced his clever progress through Fraser’s Magazine and the ever-improving pages of Punch – which wonder of the time has been infinitely obliged to him – but still we were little prepared for the keen observation, the deep wisdom, and the consummate art which he has interwoven in the slight texture and whimsical pattern of Vanity Fair.

Everybody, it is to be supposed, has read the volume by this time; and even for those who have not, it is not necessary to describe the order of the story. It is not a novel, in the common acceptation of the word, with a plot purposely contrived to bring about certain scenes, and develop certain characters, but simply a history of those average sufferings, pleasures, penalties, and rewards to which various classes of mankind gravitate as naturally and certainly in this world as the sparks fly upward. It is only the same game of life which every player sooner or later makes for himself – were he to have a hundred chances, and shuffle the cards of circumstance every time. It is only the same busy, involved drama which may be seen at any time by any one, who is not engrossed with the magnified minutiae of his own pretty part, but with composed curiosity looks on to the stage where his fellow men and women are the actors; and that not even heightened by the conventional colouring which Madame de Staël philosophically declares that fiction always wants in order to make up for its not being truth. Indeed, so far from taking any advantage of the novelist’s licence, Mr. Thackeray has hardly availed himself of the natural average of remarkable events that really do occur in this life. The battle of Waterloo, it is true, is introduced; but, as far as regards the story, it brings about only one death and one bankruptcy, which might either of them have happened in a hundred other ways. Otherwise the tale runs on, with little exception, in that humdrum course of daily monotony, out of which some people coin materials to act, and others excuses to doze, just as their dispositions may be.

It is this reality which is at once the charm and the misery here. With all these unpretending materials it is one of the most amusing, but also one of the most distressing books we have read for many a long year. We almost long for a little exaggeration and improbability to relieve us of that sense of dead truthfulness which weighs down our hearts, not for the Amelias and Georges of the story, but for poor kindred human nature. In one light this truthfulness is even an objection. With few exceptions the personages are too like our every-day selves and neighbours to draw any distinct moral form. We cannot see our way very clearly. Palliations of the bad and disappointments in the good are perpetually obstructing our judgment, by bringing what should decide it too close to that common standard of experience in which our only rule of opinion is charity. For it is only in fictitious characters which are highly coloured for one definite object, or in notorious personages viewed from a distance, that the course of the true moral can be seen to run straight – once bring the individual with his life and circumstances closely before you, and it is lost to the mental eye in the thousand pleas and witnesses, unseen and unheard before, which rise up to overshadow it. And what are all these personages in Vanity Fair but feigned names for our own beloved friends and acquaintances, seen under such a puzzling cross-light of good in evil, and evil in good, of sins and sinnings against, of little to be praised virtues, and much to be excused vices, that we cannot presume to moralise upon them – not even to judge them, – content to exclaim sorrowfully with the old prophet, “Alas! my brother!” Every actor on the crowded stage of Vanity Fair represents some type of that perverse mixture of humanity in which there is ever something not wholly to approve or to condemn. There is the desperate devotion of a fond heart to a false object, which we cannot respect; there is the vain, weak man, half good and half bad, who is more despicable in our eyes than the decided villain. There are the irretrievably wretched education, and the unquenchably manly instincts, both contending in the confirmed roué, which melt us to the tenderest pity. There is the selfishness and self-will which the possessor of great wealth and fawning relations can hardly avoid. There is the vanity and fear of the world, which assist mysteriously with pious principles in keeping a man respectable; there are combinations of this kind of every imaginable human form and colour, redeemed but feebly by the steady excellences of an awkward man, and the genuine heart of a vulgar woman, till we feel inclined to tax Mr. Thackeray with an under estimate of our nature, forgetting that Madame de Staël is right after all, and that without a little conventional rouge no human complexion can stand the stage-lights of fiction.

But if these performers give us pain, we are not ashamed to own, as we are speaking openly, that the chief actress herself gives us none at all. For there is of course a principal pilgrim in Vanity Fair, as much as in its emblematical original, Bunyan’s Progress; only unfortunately this one is travelling the wrong way. And we say “unfortunately” merely by way of courtesy, for in reality we care little about the matter. No, Becky – our hearts neither bleed for you, nor cry out against you. You are wonderfully clever, and amusing, and accomplished, and intelligent, and the Soho ateliers were not the best nurseries for a moral training; and you were married early in life to a regular blackleg, and you have had to live upon your wits ever since, which is not an improving sort of maintenance; and there is much to be said for and against; but still you are not one of us, and there is an end to our sympathies and censures. People who allow their feelings to be lacerated by such a character and career as yours, are doing both you and themselves a great injustice. No author could have openly introduced a near connexion of Satan’s into the best London society, nor would the moral end intended have been answered by it; but really and honestly, considering Becky in her human character, we know of none which so thoroughly satisfies our highest beau idéal of feminine wickedness, with so slight a shock to our feelings and proprieties. It is very dreadful, doubtless, that Becky neither loved the husband who loved her, nor the child of her own flesh and blood, nor indeed any body but herself; but as far as she is concerned, we cannot pretend to be scandalized – for how could she without a heart? It is very shocking of course that she committed all sorts of dirty tricks, and jockeyed her neighbours, and never cared what she trampled under foot if it happened to obstruct her step; but how could she be expected to do otherwise without a conscience? The poor little woman was most tryingly placed; she came into the world without the customary letters of credit upon those two great bankers of humanity, Heart and Conscience, and it was no fault of hers if they dishonoured all her bills. All she could do in this dilemma was to establish the firmest connexion with the inferior commercial branches of Sense and Tact, who secretly do much business in the name of the head concern, and with whom her “fine frontal development” gave her unlimited credit. She saw that selfishness was the metal which the stamp of heart was suborned to pass; that hypocrisy was the homage that vice rendered to virtue; that honesty was, at all events, acted, because it was the best policy; and so she practised the arts of selfishness and hypocrisy like anybody else in Vanity Fair, only with this difference, that she brought them to their highest possible pitch of perfection.

No; let us give Becky her due. There is enough in this world of ours, as we all know, to provoke a saint, far more a poor little devil like her. She had none of those fellow-feelings which make us wondrous kind. She saw people around her cowards in vice, and simpletons in virtue, and she had no patience with either, for she was as little the one as the other herself. She saw women who loved their husbands and yet teazed them, and ruining their children although they doated upon them, and she sneered at their utter inconsistency. Wickedness or goodness, unless coupled with strength, were alike worthless to her. That weakness which is the blessed pledge of our humanity was to her only the despicable badge of our imperfection. She thought, it might be, of her master’s words, “Fallen cherub! to be weak is to be miserable!” and wondered how we could be such fools as first to sin and then to be sorry. Becky’s light was defective, but she acted up to it. Her goodness goes as far as good temper, and her principles as far as shrewd sense, and we may thank her consistency for showing us what they are both worth.

There are mysteries of iniquity, under the semblance of man and woman, read of in history, or met with in the unchronicled sufferings of private life, which would almost make us believe that the powers of Darkness occasionally made use of this earth for a Foundling Hospital, and sent their imps to us, already provided with a return-ticket. We shall not decide on the lawfulness or otherwise of any attempt to depict such importations; we can only rest perfectly satisfied that, granting the author’s premises, it is impossible to imagine them carried out with more felicitous skill and more exquisite consistency than in the heroine of Vanity Fair.

The great charm and comfort of Becky is, that we may study her without any compunctions. The misery of this life is not the evil that we see, but the good and the evil which are so inextricably twisted together. It is that perpetual memento every meeting one – “How in this vile world below, Noblest things find vilest using” – that is so very distressing to those who have hearts as well as eyes. But Becky relieves them of all this pain – at least in her own person. Pity would be thrown away upon one who has not heart enough to ache even for herself. Becky is perfectly happy, as all must be who excel in what they love best. Her life is one exertion of successful power. Shame never visits her, for “Tis conscience that makes cowards of us all” – and she has none. She realizes that ne plus ultra of sublunary comfort which it was reserved for a Frenchman to define – the blessed combination of le bon estomac et le mauvais coeur: for Becky adds to her other good qualities that of an excellent digestion.

Upon the whole, we are not afraid to own that we rather enjoy her ignis fatuus course, dragging the weak and the vain and the selfish, through mud and mire, after her, and acting all parts, from the modest rushlight to the gracious star, just as it suits her. Clever little imp that she is! What exquisite tact she shows! – what unflagging good humour! – what ready self-possession! Becky never disappoints us; she never even makes us tremble. We know that her answer will come exactly suiting her one particular object, and frequently three or four more in prospect. What respect, too, she has for those decencies which more virtuous, but more stupid humanity, often disdains! What detection of all that is false and mean! What instinct for all that is true and great! She is her master’s true pupil in that: she knows what is really divine as well as he, and bows before it. She honours Dobbin in spite of his big feet; she respects her husband more than she ever did before, perhaps for the first time, at the very moment when he is stripping not only her jewels, but name, honour, and comfort off her.

We are not so sure either whether we are not justified in calling hers le mauvais coeur. Becky does not pursue any one vindictively; she never does gratuitous mischief. The fountain is more dry than poisoned. She is even generous – when she can afford it. Witness that burst of plain speaking in Dobbin’s favour to the little dolt Amelia, for which we forgive her many a sin. ‘Tis true she wanted to get rid of her; but let that pass. Becky was a thrifty dame, and liked to dispatch two birds with one stone. And she was honest, too, after a fashion. The part of wife she acts at first as well, and better than most; but as for that of mother, there she fails from the beginning. She knew that maternal love was no business of hers – that a fine frontal development could give her no help there – and puts so little spirit into her imitation that no one could be taken in for a moment. She felt that her bill, of all others, would be sure to be dishonoured, and it went against her conscience – we mean her sense – to send it in.

In short, the only respect in which Becky’s course gives us pain is when it locks itself into that of another, and more genuine child of this earth. No one can regret those being entangled in her nets whose vanity and meanness of spirit alone led them into its meshes – such are rightly served: but we do grudge her that real sacred thing called love, even of a Rawdon Crawley, who has more of that self-forgetting, all-purifying feeling for his little evil sprit than many a better man has for a good woman. We do begrudge Becky a heart, though it belong only to a swindler. Poor, sinned against, vile, degraded, but still true-hearted Rawdon! – you stand next in our affections and sympathies to honest Dobbin himself. It was the instinct of a good nature which made the Major feel that the stamp of the Evil One was upon Becky; and it was the stupidity of a good nature which made the Colonel never suspect it. He was a cheat, a black-leg, an unprincipled dog; but still “Rawdon is a man, and be hanged to him”, as the Rector says. We follow him through the illustrations, which are, in many cases, a delightful enhancement to the text – as he stands there, with his gentle eyelid, coarse moustache, and foolish chin, bringing up Becky’s coffee-cup with a kind of dumb fidelity; or looking down at little Rawdon with a more than paternal tenderness. All Amelia’s philoprogenitive idolatries do not touch us like one fond instinct of “stupid Rawdon”.

Dobbin sheds a halo over all the long-necked, loose-jointed, Scotch-looking gentlemen of our acquaintance. Flat feet and flap ears seem henceforth incompatible with evil… Dobbin –

lumbering, heavy, shy, and absurdly over modest as the ugly fellow is—is yet true to himself. At one time he seems to be sinking into the mere abject dangler after Amelia; but he breaks his chains like a man, and resumes them again like a man, too, although half disenchanted of his amiable delusion.

But to return for a moment to Becky. The only criticism we would offer is one which the author has almost disarmed by making her mother a Frenchwoman. The construction of this little clever monster is diabolically French. Such a lusus naturae as a woman without a heart and conscience would, in England, be a mere brutal savage, and poison half a village. France is the land for the real Syren, with the woman’s face and the dragon’s claws. The genus of Pigeon and Laffarge claims her for its own – only that our heroine takes a far higher class by not requiring the vulgar matter of fact of crime to develop her full powers. It is an affront to Becky’s tactics to believe that she could ever be reduced to so low a resource, or, that if she were, anybody would find it out.

Poor little Becky is bad enough to satisfy the most ardent student of ‘good books’. Wickedness, beyond a certain pitch, gives no increase of gratification even to the sternest moralist; and one of Mr. Thackeray’s excellences is the sparing quantity he consumes. The whole use, too, of the work – that of generously measuring one another by this standard – is lost, the moment you convict Becky of a capital crime. Who can, with any face, liken a dear friend to a murderess? Whereas now there are no little symptoms of fascinating ruthlessness, graceful ingratitude, or ladylike selfishness, observable among our charming acquaintance, that we may not immediately detect to an inch, and more effectually intimidate by the simple application of the Becky gauge than by the most vehement use of all Ten Commandments. Thanks to Mr. Thackeray, the world is now provided with an idea, which, if we mistake not, will be the skeleton in the corner of every ball-room and boudoir for a long time to come. Let us leave it intact in its unique point and freshness – a Becky, and nothing more.