ARISTOPHANES: CREATIVITY IN FIFTH CENTURY DRAMA

Edd. Dustin W. Dixon and Mary C. English, THE SPIRIT OF ARISTOPHANES. Edinburgh University Press. 2024. Pp. i-xvi, 1-207. £85.00/$104.00 (Hardback), reviewed by Darrell Sutton

Edd. Dustin W. Dixon and Mary C. English, THE SPIRIT OF ARISTOPHANES. Edinburgh University Press. 2024. Pp. i-xvi, 1-207. £85.00/$104.00 (Hardback), reviewed by Darrell Sutton

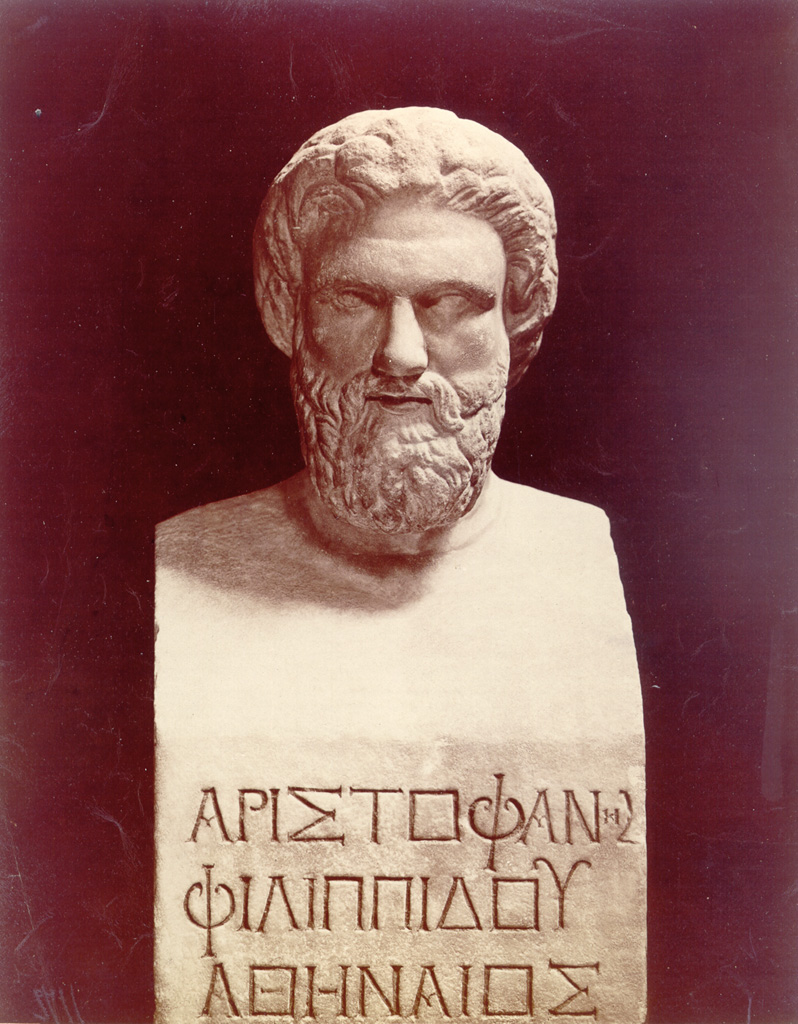

According to Aristotle, the design of dramatic plots began in Sicily. Specifics about their origins and production are founded upon conjecture, and points of contact between their derivation and comedic transformations upon reaching Athens are not easy to detect. Historical advancements in later studies of ancient comedy are simpler to trace. In Hellenistic times, the scholars of Alexandria had a hand in shaping the minds of readers who acquainted themselves with the comedies of Aristophanes. Menander’s popularity through citations was more widespread than Aristophanes in the Patristic age. Roman comedies had private readers and were preserved during Medieval period; but Byzantine scholars kept Aristophanes’ memory alive. The Renaissance saw presentations of Roman comedies before select audiences. Greek ideas continued to be inseminated into European minds by academics interested in those texts.

While American classicists focused on grammar, German speaking philologists applied techniques that British classicists happily shunned. By the time Gilbert Murray (1866-1957) offered to the public his book Aristophanes: A Study (1933), the pendulum had swung from the side of principled textual investigations of his comments on humor, religion, war and polity to more nascent academic forms of literary criticism. Evidently nostalgia was in the hearts of contemporary scholars in the West. Eventually a Victorian mindset reappeared, again within the departments of Greek and Roman classics. Classics-in-Translation courses formed the creative framework in which innovative social research began, i.e. critical theories (of gender etc.: e.g. see below T. Travillian, ‘The Body’s Borders: Violation and the Visual in the Carmina Priapea).

Past scholarship, which involved exploring political perspectives, language and persons in Aristophanic texts now are difficult to quantify amid the mass of activist studies of how his comedies were received by men [women too if they were in the audience] in ancient Greece. Longer literary analyses and shorter notes dominate current fields of study of Aristophanes’ Athenian productions and drama in general (cf. chapter 8, Dustin W. Dixon, ‘The Whetstone of Love: Helen’s Blemished Beauty’). In this book also, there are exceptions to this claim, i.e. articles that are first-rate: e.g. chapter 7: Andrew Ford, ‘…Storytelling and the Origin of Religion in the Sisyphus Fragment (43 fr.19 TrGF)’, chapter 10: William Owens, ‘Truth and Narrative in Daphis and Chloe’, chapter 12: James. J. O’hara, ‘What are the Goals of Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura?’, and chapter 13: John Bodel, ‘Not so Funny After All: On Deconstructing (And Reconstructing) the Text of Petronius’ are treats to read.

The volume under review is a tribute to the pioneering and brilliant scholarship of Jeffrey Henderson (JH), who through decades of indefatigable work distinguished himself as a commentator and translator of ancient Greek texts. He is the general editor of the Loeb Classical Library and is the William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of Greek Language and Literature at Boston University. Each article is written by one of his students. Repeatedly, expressions of gratitude to him are noted down because of an author’s appreciation of JH’s pedagogy, as well as his scholarship. There are thirteen chapters.

These papers were presented originally in a 2022 Aurelio conference dedicated to JH. Amy Richlin’s article ‘Female Genitalia Onstage in Aristophanes’ (chapter 1) opens the book. She engages throughout with JH’s scholarship in ‘The Maculate Muse: Obscene Language in Attic Comedy (1971, rev.1991). She displays an instinct for critical insight. But one has reservations. In this genre of texts, which is formally based upon typological study, lexical nuances are only as certain as the interpreter’s perceptions and convictions. The contexts in which she and JH envision find crudity in places Hellenes would have overlooked as nothing more than strained attempts at humor. New realities were created by the scholars’ imaginations. Undoubtedly, decades of etymological review have superimposed upon Greek comedy modern ideas that would seem odd to writers of ancient comedy. Her comments lead to imprecision at times.

In ‘Let Loose the Melodies of Holy Hymns’ (chapter 2), Daniel Libatique discusses ‘the interaction between Aristophanes’ Birds and Sophocles’ Tereus by exploring how Aristophanes’ choices in attributing speech or silence to his characters allow him to flip the hierarchy of power in Sophocles’ play upside down’ (p.20). This piece is well-written, teaching readers inter alia that tragedy allowed for more ‘female speaking characters’ than other forms of drama.

Chapter 3. Mary C. English, in ‘Performing Ritual Sacrifice in Aristophanes’ Peace and Birds’, attempted to do two things at once: (1) explain Aristophanes’ [ir]reverence toward the Gods while (2) giving readers insight into animal sacrifices. Her statements are vague. She does not know where to stand on issues related to comedic civil discourse and the boundaries to which comedy needed to adhere, or if it needed to adhere to any civic rules at all. It is doubtful that comedy offered any ‘fantastic solutions to common problems (p.40) of the day. Another possible kind of irreverence is viewed from the perspective of staging. ‘Will Trygaeus and Peisetaerus actually perform their sacrifices to untraditional gods onstage?’(p.43). The answer from the texts is clear: no, they did not. Fragments used to deduce support for the author’s claims are misjudged and stretched to the limit, so much so that on page 46 fn.34 we have a long analogy of Archie Bunker, from the American TV comedy All in the Family, as a means to understand episodes from Peace and Birds.

Among the hundreds of published papers that explore Aristophane’s political stances through his supposed rudeness and crudeness, I-Kai Jeng (chapter 4), in ‘Political Ambition and Poetry in Aristophanes’ Birds and Plato’s Aristophanes’, believes that Birds ‘is sparse with allusions to contemporaneous political affairs’ and that its ‘political stance is not easy to discern’ (p.49); but he believes ‘it remains a political play’ (p.51). The rationale here is questionable. Moreover, he maintains that ‘The power of language constitutes a significant part of the play’s reflection on politics’ (p.55). The middle paragraph on page 56 lists reasons that lead I-Kai ‘to believe that Birds evaluates certain political methods positively without recommending them in practice.’

On page 54 he referred to ‘signs that Aristophanes in the end prefers political moderation instead of what Birds portrays.’ These fields have been tilled many times before. His interpretative decisions, however, regarding Greek terms often are detached from historical meaning. Since he sees ambiguity in too many places where the lexical data is clear, he leaves little room for establishing confirmable truths.

I-Kai writes ‘Plato’s Dialogue occurs against a background in which a connection between a desire to rule the world and indifference to gods is lurking. This historical background, although barely alluded to in either work, nevertheless appears as fertile ground for exploring human longing and its attitude toward the divine’ – italics mine (p.57). Directed by inconspicuous details, he wants readers to suppose that Aristophanes in Birds and Symposium might be saying ‘opposite things’, but not really. The contrary features can be reconciled according to I-Kai. The conclusions drawn in this article are imaginative, as fanciful as Aristophane’s Speech in Plato’s Symposium.

Chapter 5. Anne Mahoney, ‘Sophocles and Happy Endings’ labors hard to differentiate between tragedy and comedy, citing Plato and the Romans. Sometimes huge difficulties need to be surmounted when tackling a perceivably simple issue. Her knowledge is encyclopedic. It is not farfetched to merely say in tragedy select characters are used to illustrate a variety of discomforts imposed upon them in the play. In a brief compass she proves that happy endings are not antithetical to ‘tragic’ productions. Unlike her view, other inferences may be drawn rather than her suggestion ‘that it may be true that a play whose main characters are of low status is always a comedy’ (P.66). Her paper is well-designed, thoughtful and balanced in its approach to the subject.

Emily Austin, chapter 6 tries a novel approach when attempting to define ‘heroism’ by using grammatical middle voice grammatical terms. In ‘Heroism in the Middle in Sophocles’ Philoctetes’, that character’s pain and suffering is used as a canvas on which to depict him as a man to whom kleos/glory is illusory in normal terms. She is honest when she says, “There is no single verb or noun that describes this kind of ‘middle-voice’ heroism” (p.82). Her view imagines that “these ‘middle-voice’ passages evoke a sense of achievement.’ She concludes her paper by stating she has used “a framework of grammatical ‘middle-voice’ in order to move beyond an active-passive binary in how we view suffering and action on the Athenian tragic stage” (p.87). She has done good work in other spheres; but I was alerted to where this confusing path might take readers at footnote #2, page 76. This theoretical form of middle voice linguistics misdirects readers away from clear insights and sound philological methods.

Chapter 9. Chris Synodinos, in ‘Virginity and the Post-mortem State of the Body: Reading Mary and Hippolytus in Dialogue’, attempts to “put the figure of Mary in dialogue with representations of the Greek mythical hero”, by presenting some literary correspondence between the two characters. One’s high expectations were met with disappointment. This paper needed editorial revision. Although everywhere there is food for thought, readers will hardly scan ten sentences on any page without an error of fact or distortion of truth disclosing itself. CS begins by asserting that First Corinthians 15:51 somehow is relevant to Mary’s dormition and bodily assumption to heaven (p.119). Another false and audacious claim is made when he argues, ‘that belief in the Virgin’s bodily assumption arose as a corollary of her divine maternity, which is itself inextricably linked to her perpetual virginity – a fundamental conviction of the Early Church and central to major branches of today’s mainstream Christianity’ (p.129). Those Marian dogmas are not in any of the writings of Apostolic Fathers; but in non-canonical texts which he intermingles with canonical ones, leading the reader to believe these beliefs are held wherever the Bible is read and believed, even by Protestants. Not until the Medieval period do these views take formal shape as a Roman Catholic viewpoint, later taking root in a few smaller Eastern Catholic sects. Those notions hardly are “mainstream”. Besides, what do they have to do with classical literary figures? His elucidations of each Greek passage, which is supposedly comparable to Hippolytus’ character, may be safely overlooked.

Tyler Travillian is correct that the poems discussed by him in chapter 11 do not fit the traditional genre of Roman satire; but it is uncertain if they all are political. The Carmina Priapea is a strongly sexually oriented poem. He examines the axioms and witticisms of the CP. It is best to let him speak in his own words. Citing the ‘sensory experiences’ and the ‘all-too-real sonic caresses of the Priapea as poetry’ noted in Elizabeth Young’s article, ‘The Touch of the Cinaedus: Unmanly Sensations in the Carmina Priapea’, TT offers his view:

‘I suggest that another of the senses, the gaze, shows the reader a way to combine and expand on… Young’s readings, which use sexual humor and invective to enforce social norms on those lower in the social hierarchy, and a Subversive Reading that destabilizes and re-evaluates the elite masculinity that the poems at first appear to reinforce (p.145).

He applies this technique vigorously. His translations are apt. But very little historical context is supplied. Therefore, the milieu, as described by the author, is at times enigmatic. Delving into CP’s mysteries requires clear explication of attitudes of that day, not of ours. The impression given by the author is of an ancient Roman culture in which all behaviour was exhibited unashamedly. Granted, the Romans were not prudes. But the people mentioned in CP are not representatives of society in general any more than the content of this article is accessible or acceptable to readers of Latin in every sphere of modern suburban and rural life.

————–

Some isolated comments. An introductory article on the last 50 years of scholarship on Aristophanes, and JH’s contribution to it, would have been better than the now standard opening pages that tell you what you can expect from each author. Indeed, a critical comparison of JH’s Loeb editions with Alan Sommerstein’s critical edition of Aristophanes (Aris & Phillips) would have been beneficial. Only a small amount of textual criticism is included. How JH engaged the texts of The Bude Aristophane or N.G. Wilson’s OCT Aristophanis Fabvlaeneeded extensive debate. JH’s groundbreaking work on ‘obscenities’ is cited by all who work in this field. Nonetheless, there were no critical analyses of his conclusions in this small volume. Justifiably his students copy him in the use of bawdy language when translating select Greek expressions. Several authors credit JH for inspiring ideas that it seems unlikely that he would have promoted.

In some places, the English glosses overstress for readers what Aristophanes could not have meant. The editors, and several of the authors, love the use of words like ‘subvert’ and ‘subversive’. In their minds Aristophanes’ comedies were always intended to induce far more than humor, as if they were intended to be literary weapons for challenging or overthrowing opinion. Understanding that Greek rulership in the fifth century would suppress ones who would foment revolts should disabuse readers of the insertion of so many subversive texts. Aristophanes did employ ebullient farce in his presentations, which mirrored what he may have deemed perverse societal norms. Comedic remarks were not unlawful unless it seduced people to behave criminally. So much for ἰσηγορία/ free speech! Amy Richlin cited the sexual reversion to conservatism, noted in the early 1990s by JH. That statement is political, scurrilous and patently false. Fornication (free-spiritism) in the USA (or the West) has hardly reversed course since the 1960s. As well, their assumptions are proof of an ivy league line of reasoning that misconstrues the logic behind lifestyle choices of poor or unrefined denizens who live worlds away from liberal academia.

Aristophanes’ showed a fondness for inter-lacing his comedies with his personal views on Euripides. German classical philologists of the 19th century were models of how ancient contexts, when rightly defined, would yield profitable interpretations that are not restricted by modern cultural sentiments. Psychoanalysis can be applied to mental states of scholars who, like his audiences, are fascinated by Aristophanes’ obscenities, and we can look forward to an account of the psychological side effects exhibited by 20th and 21st century students who read the works of the most recent editors and commentators of Aristophanes.

As a piece of research, The Spirit of Athens is helpful for instruction in private tutorials. If lecturers read it closely, by the book’s end, something becomes apparent: the fact that scholars of another generation made use of scholarly tools, arguing toward logical conclusions by distinct means, that are wholly unfamiliar to those trained in the other one.

This review only dealt with issues that seemed questionable. Progress in the study of Old comedy will carry on. Indigestible material aside, several contributions stand out and will be useful for further reference work. The festschrift is misnamed. Most of the papers do not focus on Aristophanes.

Classicist Darrell Sutton is a frequent contributor to QR