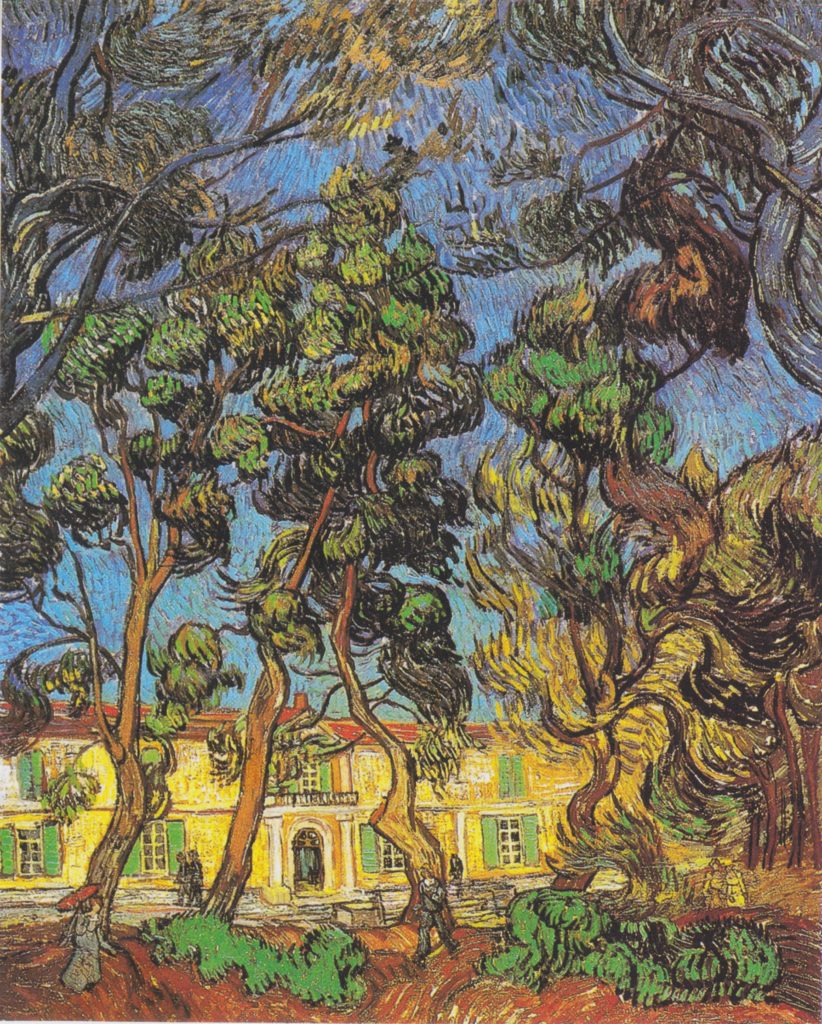

Van Gogh, Garden of Saint Rémy Asylum

Van Gogh and Britain

Van Gogh and Britain, Tate Britain, 27th March 2019, exhibition curated by Carol Jacobi

Van Gogh and Britain, edited by Carol Jacobi, Tate Publishing, London, 2019, 240 pp

Reviewed by Leslie Jones

From 1873-1876, Van Gogh was a trainee art dealer in London with the Goupil Gallery. He evidently admired numerous British authors, notably Thomas Carlyle, Charles Dickens and George Eliot but also poets and dramatists such as Keats and Shakespeare. Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress was for him a “beloved book”. Several of the writers he revered had addressed the seemingly intractable social problems generated by industrial capitalism.

While in London, Van Gogh collected prints, particularly those by Gustave Doré, whose “resolute honesty” he respected. His only painting of London, The Prison Courtyard (1890), which is included in the exhibition is, as he euphemistically put it, a ‘translation’ of Dore’s print Newgate: The Exercise Yard, from London a Pilgrimage (1872). Even the tiny, symbolic detail of two butterflies at the top of the engraving is repeated in the painting (see Van Gogh and Britain, page 95). In similar fashion, the watercolour Woman Sewing and Cat (October-November 1881) is indebted to Doré’s The Song of the Shirt, an illustration of Thomas Hood’s eponymous poem about exploited seamstresses.

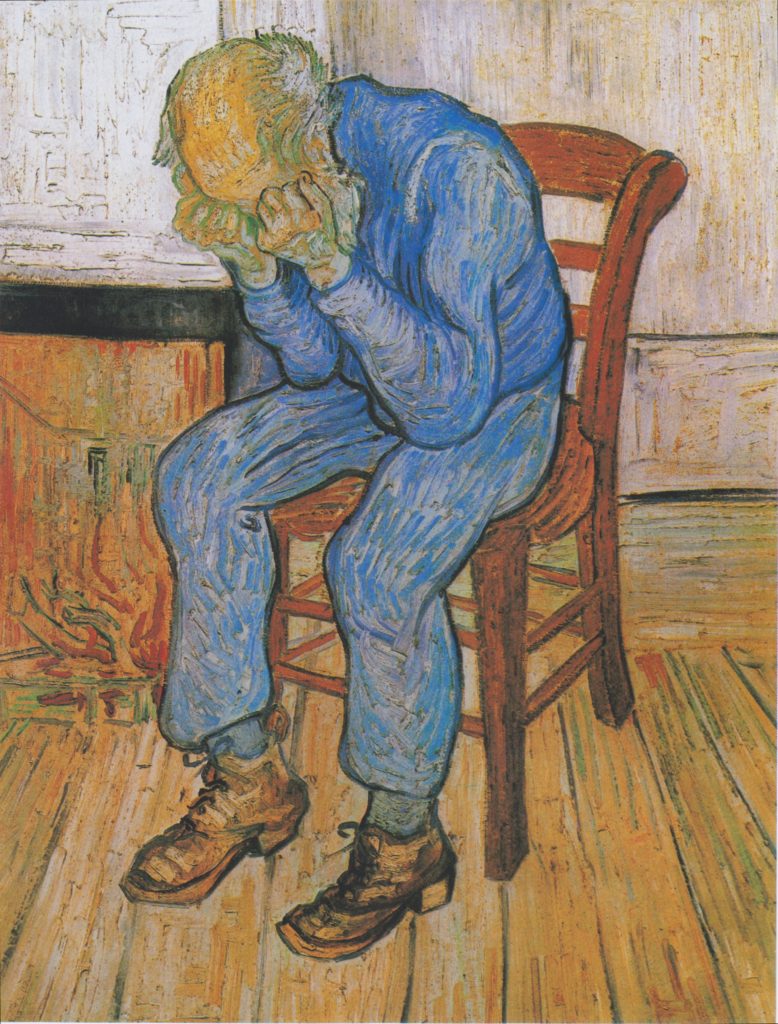

In the drawing Sorrow (April 1882), reminiscent of Edvard Munch, we see a naked pregnant woman. The model was the prostitute and sometime seamstress Sien Hoornik, whom Vincent had met at a soup kitchen in the Hague and who subsequently drowned herself. She was also the model for Mourning Woman Seated on a Basket (Feb-March 1883). Van Gogh’s uncanny ability to depict human emotions expressed through body language is also demonstrated by the lithograph At Eternity’s Gate (November 1882) and the subsequent painting Sorrowing Old Man, ‘At Eternity’s Gate’ (May 1890).

Van Gogh, Sorrowing Old Man

Vincent considered his position as an outsider, plagued with mental illness and poverty, as a metaphorical prison, which prevented him from succeeding. In Arles, in late 1888 and early 1889, he was confined in hospital by order of the police, after complaints from his neighbours about his behaviour, including self-harming. And subsequently, in the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole at Saint-Rémy, which he had entered voluntarily, he complained that “The prison was crushing me…”, blaming the other inmates and Doctor Gachet for a subsequent relapse.

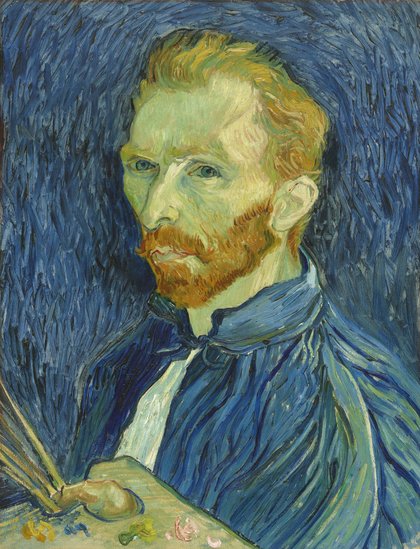

Referring to his self-portrait (1889), completed at Saint-Rémy, he remarked “I was thin, pale as a devil”. The artist’s unflinching honesty is evident in this picture, as in the earlier Self-Portrait (Autumn 1887). There are echoes in these works of the ‘Heads of the People Drawn from Life’, such as ‘The British Rough’, which were published in the Graphic and which he acquired in the early 1880’s.

Van Gogh, Self Portrait

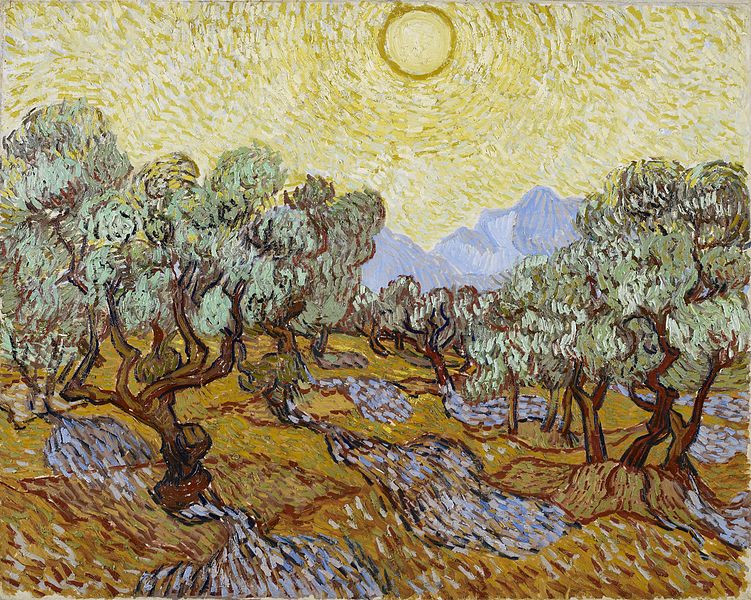

Depictions of the asylum itself, such as Path in the Garden of the Asylum (1889), The Stone Bench in the Asylum at Saint-Rémy (1889), and Hospital at Saint-Rémy (October 1889) are also featured in this exhibition. Ditto, studies of the surrounding countryside, notably Olive Trees (June 1889). In Horse Chestnut Tree in Blossom (May 1887) and other contemporaneous works, Van Gogh adapted the pointillist technique to brilliant effect. Devised by Georges Seurat, it was introduced to him by Camille Pissarro (Van Gogh and Britain, Trees, page 138). He once referred to “the stronger light, [of Provence] the blue sky that teaches one to see”.

Lead curator Dr Carol Jacobi and her colleagues have done us sterling service, tracing not just the intellectual and painterly influences on Van Gogh but also his reciprocal influence on a subsequent generation of British artists – éblouissant.

Van Gogh, Olive Trees

Editorial note: all of the artist’s correspondence is now available in a new edition as Vincent van Gogh – the Letters. The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition. See ‘Van Gogh, by himself’, Quarterly Review, Spring 2010

Dr LESLIE JONES is the Editor of QR

Like this:

Like Loading...

Van Gogh and Britain

Van Gogh, Garden of Saint Rémy Asylum

Van Gogh and Britain

Van Gogh and Britain, Tate Britain, 27th March 2019, exhibition curated by Carol Jacobi

Van Gogh and Britain, edited by Carol Jacobi, Tate Publishing, London, 2019, 240 pp

Reviewed by Leslie Jones

From 1873-1876, Van Gogh was a trainee art dealer in London with the Goupil Gallery. He evidently admired numerous British authors, notably Thomas Carlyle, Charles Dickens and George Eliot but also poets and dramatists such as Keats and Shakespeare. Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress was for him a “beloved book”. Several of the writers he revered had addressed the seemingly intractable social problems generated by industrial capitalism.

While in London, Van Gogh collected prints, particularly those by Gustave Doré, whose “resolute honesty” he respected. His only painting of London, The Prison Courtyard (1890), which is included in the exhibition is, as he euphemistically put it, a ‘translation’ of Dore’s print Newgate: The Exercise Yard, from London a Pilgrimage (1872). Even the tiny, symbolic detail of two butterflies at the top of the engraving is repeated in the painting (see Van Gogh and Britain, page 95). In similar fashion, the watercolour Woman Sewing and Cat (October-November 1881) is indebted to Doré’s The Song of the Shirt, an illustration of Thomas Hood’s eponymous poem about exploited seamstresses.

In the drawing Sorrow (April 1882), reminiscent of Edvard Munch, we see a naked pregnant woman. The model was the prostitute and sometime seamstress Sien Hoornik, whom Vincent had met at a soup kitchen in the Hague and who subsequently drowned herself. She was also the model for Mourning Woman Seated on a Basket (Feb-March 1883). Van Gogh’s uncanny ability to depict human emotions expressed through body language is also demonstrated by the lithograph At Eternity’s Gate (November 1882) and the subsequent painting Sorrowing Old Man, ‘At Eternity’s Gate’ (May 1890).

Van Gogh, Sorrowing Old Man

Vincent considered his position as an outsider, plagued with mental illness and poverty, as a metaphorical prison, which prevented him from succeeding. In Arles, in late 1888 and early 1889, he was confined in hospital by order of the police, after complaints from his neighbours about his behaviour, including self-harming. And subsequently, in the psychiatric hospital of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole at Saint-Rémy, which he had entered voluntarily, he complained that “The prison was crushing me…”, blaming the other inmates and Doctor Gachet for a subsequent relapse.

Referring to his self-portrait (1889), completed at Saint-Rémy, he remarked “I was thin, pale as a devil”. The artist’s unflinching honesty is evident in this picture, as in the earlier Self-Portrait (Autumn 1887). There are echoes in these works of the ‘Heads of the People Drawn from Life’, such as ‘The British Rough’, which were published in the Graphic and which he acquired in the early 1880’s.

Van Gogh, Self Portrait

Depictions of the asylum itself, such as Path in the Garden of the Asylum (1889), The Stone Bench in the Asylum at Saint-Rémy (1889), and Hospital at Saint-Rémy (October 1889) are also featured in this exhibition. Ditto, studies of the surrounding countryside, notably Olive Trees (June 1889). In Horse Chestnut Tree in Blossom (May 1887) and other contemporaneous works, Van Gogh adapted the pointillist technique to brilliant effect. Devised by Georges Seurat, it was introduced to him by Camille Pissarro (Van Gogh and Britain, Trees, page 138). He once referred to “the stronger light, [of Provence] the blue sky that teaches one to see”.

Lead curator Dr Carol Jacobi and her colleagues have done us sterling service, tracing not just the intellectual and painterly influences on Van Gogh but also his reciprocal influence on a subsequent generation of British artists – éblouissant.

Van Gogh, Olive Trees

Editorial note: all of the artist’s correspondence is now available in a new edition as Vincent van Gogh – the Letters. The Complete Illustrated and Annotated Edition. See ‘Van Gogh, by himself’, Quarterly Review, Spring 2010

Dr LESLIE JONES is the Editor of QR

Share this:

Like this: