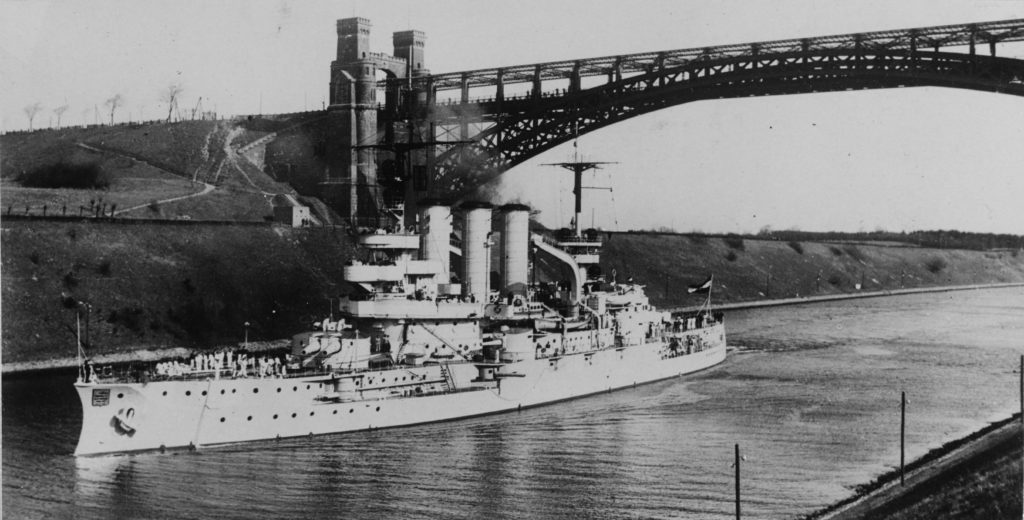

German battleship Hessen transiting the Kiel Canal

Kiel Bill

William Hartley, alone on a wide wide sea

The Kiel Canal isn’t popular with ship’s crews, even though it cuts out a long haul around the Jutland Peninsula when entering the Baltic. A German pilot and helmsman come on board to take charge of the ship and during transit no routine maintenance work such as painting or welding is allowed, due to the proximity of houses. This means the crew are on duty but largely idle during the twelve hour passage. Ships proceed at a stately pace, sometimes being overtaken by cyclists on the adjacent path and occasionally it becomes necessary to heave to and let a larger vessel pass. The MV Kristin Schepers is less than 10,000 tonnes which may seem substantial but she is a minnow compared to the huge bulk carriers which get right of way. Up on the bridge with the Germans doing the work, we use our elevated position to look in the windows of canal side towns.

The ship is German owned but Cyprus flagged and most of the officers are Russian. Down in the mess, mealtime entertainment is non stop Russian TV which seems to consist largely of Mr Putin’s activities and occasionally his hapless looking Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin. It can be as many as five very steep flights of stairs to descend to the mess deck for meals. Function shapes form on the modern freighter and all non-cargo related space is squeezed into a tall narrow structure, where the crew eat and sleep. At the top, overlooking our load of containers, is the bridge.

Entering the Baltic after dropping the pilot, we journey along the coast only losing sight of land somewhere beyond the mouth of the Oder. A ship this size when out at sea can routinely operate with only a single watch keeper, since most functions are automated and appear on a row of screens mounted on a console. There is no ship’s wheel as such these days – everything is push button. For someone who is just along for the ride it’s a pleasant experience being up on the bridge, with just the Captain for company, at least when the Baltic is behaving itself. We crossed the North Sea two days ago following a late sailing from Immingham and so far the March weather has been reasonably good.

Our departure from Immingham was delayed by sixteen hours due to no berth being available, consequently it was necessary to stand out at the mouth of the Humber until another ship had sailed. Delays are an integral part of merchant shipping and because of this unloading began late in the evening. The Filipino seamen had the unenviable task of being on deck in the pouring rain until the Dockers had finished their shift. Work resumed before dawn with a procession of lorries fetching and carrying containers. Loading followed unloading until containers were once again stacked six high and the journey across the North Sea to the canal could begin.

Our first port is to be Klaipeda in Lithuania which lies on the Akmena-Dane River and is the most northerly ice free port in the Baltic. It is a good example of the strange geography, both physical and political, along this coast. To enter the port it’s necessary to pass the Samland Peninsula, a long finger of land stretching out into the sea. Close by lies the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad. Klaipeda, formerly known as Memel, an ancient hanseatic port, was once Germany’s northernmost city and lay in East Prussia. This is reflected in the architecture of the old town and illustrates just how far German influence used to extend.

As we sail upriver much of the local naval strength seems to be moored here. There are British built minesweepers in the Lithuanian navy and next to where we dock a corvette is moored. According to our schedule this was meant to be a quick turn around but the formerly calm Baltic weather has now gone and we are in the midst of a gale. The next day on television, structural damage to Kaliningrad takes priority over Mr Putin’s activities. It is more than twelve hours before the wind drops enough to allow us to depart. Given the height of the containers heavy seas would be too much of a risk. Only the huge bulk carriers are able to sail in this weather.

Ships the size of the Kristin carry a very small crew; we have a dozen in total and the space given over to accommodation is limited. Unlike on the big ships where there may be some recreational facilities and even a gym, officers and crew have only their messes. There is scarcely any place to go beyond this due to the ubiquitous containers. As a consequence, life can be quite claustrophobic and crews need to get on. The lingua franca of international shipping is English, meaning everyone onboard uses a second language.

Out of Klaipeda we head west. The sea is still quite lively and whilst a bigger vessel can probably absorb the worst of it, getting about on stairs and ladders requires caution and an ability to anticipate the roll of the ship. Approaching our next port Gdynia, the weather deteriorates once more and as it grows dark sleet begins to fall. Manoeuvring can be difficult in a dock basin already crowded with ships; darkness and poor weather add to the challenges. To reach our berth, skipper and pilot have to effectively swing the ship stern first through ninety degrees then reverse her into a gap between two other vessels. This was undertaken by a Russian and a Pole communicating in English. It puts car parking problems into perspective.

Unloading allows additional light into the forward facing cabins. This is a temporary benefit. It takes only four seconds for an overhead crane to lower its load and before long the only view will be a new stack of containers. Two Polish officials also come on board and a few minutes later an alarm sounds with a recorded message ordering the crew to abandon ship. This is a safety drill which the officials wish to observe. Although a boat can be lowered, the fastest way is via an escape pod mounted over the stern. The only problem is that it hangs at a 45 degree angle, so it’s necessary to lower oneself through a hatch and find a seat as quickly as possible. Imagine trying to get into an aircraft seat with your knees level to your chest. Simultaneously your neighbour is trying to do the same thing.

Our final port is to be Szczecin another old German town formerly known as Stettin, which lies around 60 miles inland up the Oder River on the Dabie Lake. To get there we sail through flat empty countryside with forests and huge reed beds. Hardly anyone seems to live here and wildlife flourishes. Boar wander along the river banks unconcerned by passing ships and sea eagles dive for fish close to our stern. The first indication that we are nearing port comes when we see colliers tied up next to a mountain of coal. Poland still has thousands of miners at work. The EU might disapprove but the product is shipped out on the river. Szczecin itself is a city with an attractive skyline though the actual waterfront is less interesting than Gdynia. Once again the succession of Lorries and tractor units appear and this time the work is carried out in bright sunshine. Our return journey takes us along the coast from Polish to German Pomerania past Peenemunde. Interestingly the site is listed on the ‘European Route of Industrial Heritage’ though it doesn’t seem like a good fit with such ‘wonders’ as the Norwegian Sawmill Museum. Brussels describes it as being of note for ‘production and manufacturing’ and the ‘application of power’. Outside the blandly named ‘Museum of Industrial Heritage’, a V2 rocket is parked. This may clear up any ambiguities about the term ‘application of power’.

Freighters still carry most of our trade and whilst the big ships do so over long distances smaller vessels like the Kristin have their place, being versatile enough to enter any port and make a fast turn around. Travelling on a freighter means close contact with a world which is unfamiliar to most of us and rarely features in the media. The crews work long hours and live in cramped conditions. Weather and the vagaries of seaports means they have to accept operating conditions quite unlike most shore based jobs.

Bill Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Like this:

Like Loading...

Kiel Bill

German battleship Hessen transiting the Kiel Canal

Kiel Bill

William Hartley, alone on a wide wide sea

The Kiel Canal isn’t popular with ship’s crews, even though it cuts out a long haul around the Jutland Peninsula when entering the Baltic. A German pilot and helmsman come on board to take charge of the ship and during transit no routine maintenance work such as painting or welding is allowed, due to the proximity of houses. This means the crew are on duty but largely idle during the twelve hour passage. Ships proceed at a stately pace, sometimes being overtaken by cyclists on the adjacent path and occasionally it becomes necessary to heave to and let a larger vessel pass. The MV Kristin Schepers is less than 10,000 tonnes which may seem substantial but she is a minnow compared to the huge bulk carriers which get right of way. Up on the bridge with the Germans doing the work, we use our elevated position to look in the windows of canal side towns.

The ship is German owned but Cyprus flagged and most of the officers are Russian. Down in the mess, mealtime entertainment is non stop Russian TV which seems to consist largely of Mr Putin’s activities and occasionally his hapless looking Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin. It can be as many as five very steep flights of stairs to descend to the mess deck for meals. Function shapes form on the modern freighter and all non-cargo related space is squeezed into a tall narrow structure, where the crew eat and sleep. At the top, overlooking our load of containers, is the bridge.

Entering the Baltic after dropping the pilot, we journey along the coast only losing sight of land somewhere beyond the mouth of the Oder. A ship this size when out at sea can routinely operate with only a single watch keeper, since most functions are automated and appear on a row of screens mounted on a console. There is no ship’s wheel as such these days – everything is push button. For someone who is just along for the ride it’s a pleasant experience being up on the bridge, with just the Captain for company, at least when the Baltic is behaving itself. We crossed the North Sea two days ago following a late sailing from Immingham and so far the March weather has been reasonably good.

Our departure from Immingham was delayed by sixteen hours due to no berth being available, consequently it was necessary to stand out at the mouth of the Humber until another ship had sailed. Delays are an integral part of merchant shipping and because of this unloading began late in the evening. The Filipino seamen had the unenviable task of being on deck in the pouring rain until the Dockers had finished their shift. Work resumed before dawn with a procession of lorries fetching and carrying containers. Loading followed unloading until containers were once again stacked six high and the journey across the North Sea to the canal could begin.

Our first port is to be Klaipeda in Lithuania which lies on the Akmena-Dane River and is the most northerly ice free port in the Baltic. It is a good example of the strange geography, both physical and political, along this coast. To enter the port it’s necessary to pass the Samland Peninsula, a long finger of land stretching out into the sea. Close by lies the Russian exclave of Kaliningrad. Klaipeda, formerly known as Memel, an ancient hanseatic port, was once Germany’s northernmost city and lay in East Prussia. This is reflected in the architecture of the old town and illustrates just how far German influence used to extend.

As we sail upriver much of the local naval strength seems to be moored here. There are British built minesweepers in the Lithuanian navy and next to where we dock a corvette is moored. According to our schedule this was meant to be a quick turn around but the formerly calm Baltic weather has now gone and we are in the midst of a gale. The next day on television, structural damage to Kaliningrad takes priority over Mr Putin’s activities. It is more than twelve hours before the wind drops enough to allow us to depart. Given the height of the containers heavy seas would be too much of a risk. Only the huge bulk carriers are able to sail in this weather.

Ships the size of the Kristin carry a very small crew; we have a dozen in total and the space given over to accommodation is limited. Unlike on the big ships where there may be some recreational facilities and even a gym, officers and crew have only their messes. There is scarcely any place to go beyond this due to the ubiquitous containers. As a consequence, life can be quite claustrophobic and crews need to get on. The lingua franca of international shipping is English, meaning everyone onboard uses a second language.

Out of Klaipeda we head west. The sea is still quite lively and whilst a bigger vessel can probably absorb the worst of it, getting about on stairs and ladders requires caution and an ability to anticipate the roll of the ship. Approaching our next port Gdynia, the weather deteriorates once more and as it grows dark sleet begins to fall. Manoeuvring can be difficult in a dock basin already crowded with ships; darkness and poor weather add to the challenges. To reach our berth, skipper and pilot have to effectively swing the ship stern first through ninety degrees then reverse her into a gap between two other vessels. This was undertaken by a Russian and a Pole communicating in English. It puts car parking problems into perspective.

Unloading allows additional light into the forward facing cabins. This is a temporary benefit. It takes only four seconds for an overhead crane to lower its load and before long the only view will be a new stack of containers. Two Polish officials also come on board and a few minutes later an alarm sounds with a recorded message ordering the crew to abandon ship. This is a safety drill which the officials wish to observe. Although a boat can be lowered, the fastest way is via an escape pod mounted over the stern. The only problem is that it hangs at a 45 degree angle, so it’s necessary to lower oneself through a hatch and find a seat as quickly as possible. Imagine trying to get into an aircraft seat with your knees level to your chest. Simultaneously your neighbour is trying to do the same thing.

Our final port is to be Szczecin another old German town formerly known as Stettin, which lies around 60 miles inland up the Oder River on the Dabie Lake. To get there we sail through flat empty countryside with forests and huge reed beds. Hardly anyone seems to live here and wildlife flourishes. Boar wander along the river banks unconcerned by passing ships and sea eagles dive for fish close to our stern. The first indication that we are nearing port comes when we see colliers tied up next to a mountain of coal. Poland still has thousands of miners at work. The EU might disapprove but the product is shipped out on the river. Szczecin itself is a city with an attractive skyline though the actual waterfront is less interesting than Gdynia. Once again the succession of Lorries and tractor units appear and this time the work is carried out in bright sunshine. Our return journey takes us along the coast from Polish to German Pomerania past Peenemunde. Interestingly the site is listed on the ‘European Route of Industrial Heritage’ though it doesn’t seem like a good fit with such ‘wonders’ as the Norwegian Sawmill Museum. Brussels describes it as being of note for ‘production and manufacturing’ and the ‘application of power’. Outside the blandly named ‘Museum of Industrial Heritage’, a V2 rocket is parked. This may clear up any ambiguities about the term ‘application of power’.

Freighters still carry most of our trade and whilst the big ships do so over long distances smaller vessels like the Kristin have their place, being versatile enough to enter any port and make a fast turn around. Travelling on a freighter means close contact with a world which is unfamiliar to most of us and rarely features in the media. The crews work long hours and live in cramped conditions. Weather and the vagaries of seaports means they have to accept operating conditions quite unlike most shore based jobs.

Bill Hartley is a former Deputy Governor in HM Prison Service

Share this:

Like this: