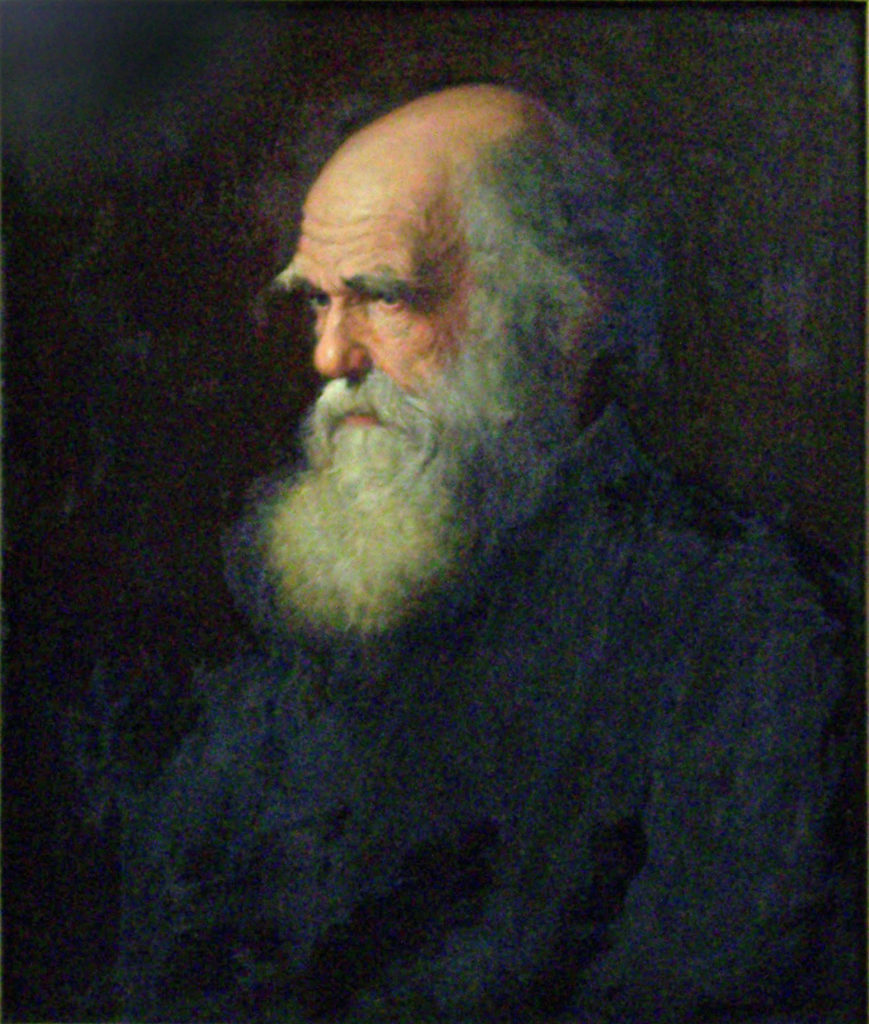

Charles Darwin, painting by Walter William Ouless, 1875

Deconstructing Darwin

Charles Darwin: Victorian Mythmaker by A.N. Wilson, published by John Murray, 2017, £25, hardback, reviewed by Gerry Dorrian

Some of literature’s most unreliable narrators can be found in the field of biography. How appropriate, then, that A.N. Wilson devotes much of Charles Darwin: Victorian Mythmaker to an examination of the naturalist’s self-reconstruction in his autobiography. In doing so, Wilson is endeavouring not only to demonstrate Darwin’s contribution to eugenics in the twentieth century but also arguably to occlude his (Wilson’s) embrace of eugenics at the start of the twenty-first.

As the author observes, Darwin erased from his history the evolutionary theories of his grandfather Erasmus Darwin, his parents, at least one schoolteacher and his fellow officers on the Beagle, whom his disappointed captain (later Admiral) FitzRoy bitterly referred to as “the ladder by which you mounted to a position where your…talent could be thoroughly demonstrated”. He also failed to mention adumbrations of his theory by Edward Blyth and Georges Cuvier, giving the impression that he came up with evolution through inspiration as opposed to osmosis.

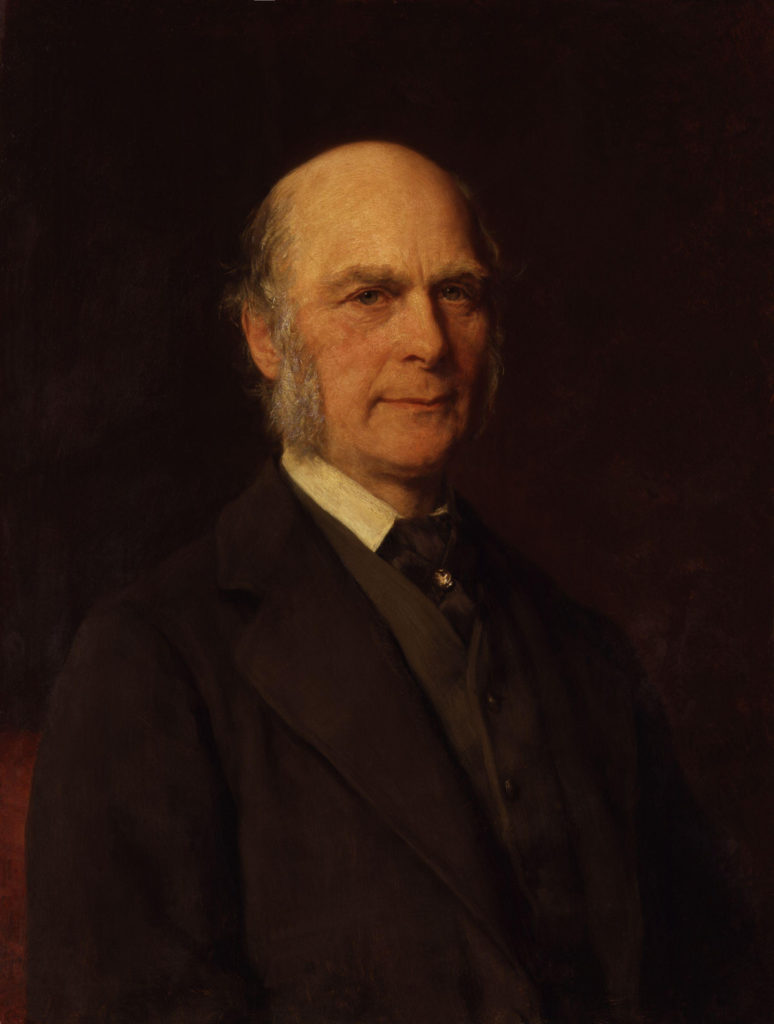

But Darwin’s revisionism parallels Wilson’s own. In a 2002 article for the Daily Telegraph, he proclaimed that Our future lies with eugenics, and he described Francis Galton, Darwin’s cousin, who invented the term eugenics, as “kindly”. In this his latest work, however, Wilson informs us that “Francis Galton developed the ideas of The Descent of Man into a full-blown programme of eugenics with the aim of eliminating the weak and undesirable.” (But see Editorial note)

What changed? Did the global financial crisis which started with the Lehman Brothers’ creative accounting and which is still rolling on rob Wilson of the chance to repeat the claim in his Telegraph article that “the overwhelming number of criminals come from stock that is violent and stupid”?

The first edition of Malthus’s Principles of Population was published in 1798, but Wilson notes that it only ascended to the status of holy writ in 1808 when the Decree of Milan, enacted the previous year by Napoleon to block supplies to Great Britain, caused imports of grain to fall to a twentieth of their 1807 figure and focussed bien-pensant hysteria on the incipient working classes, whose vigour had yet to be drained by the worst excesses of the Industrial Revolution. However, although Wilson points to a loosening of aristocratic control with the Great Reform Act of 1832, he misses a chance to comment either way on the effect that this and successive Acts that widened the franchise had on Darwin, no friend of equality as his repeated references to “savages” in The Descent of Man make clear.

The 1867 Reform Act began the extension of the franchise to the working classes, causing Bagehot to complain that “the rich and wise are not to have, by explicit law, more votes than the poor and stupid”. And in The Descent of Man (1871), Darwin maintained that “The greater death rate of infants in the poorest classes is…very important”. Conflating wealth with wisdom and the right to a say in the governance of one’s country has been a troubling aftermath, likewise, of June 2016’s European Union Membership Referendum. Wilson, for one, came out in favour of Brexit at an Indian literature festival in November 2017.

This book admittedly provides a detailed insight into Darwin’s life and Victorian times and was certainly the product of far more work than went into Wilson’s whistle-stop tour of Hitler. But the reader sometimes feels like a witness to a damage-limitation exercise aimed at decoupling the worst horrors of the twentieth century from the man central to the network wherein those horrors had their genesis. (But see Editorial note)

Cambridge was Darwin’s alma mater but it also contains an NHS hospital site named after his daughter-in-law, Ida Darwin. As with many things Darwin-related, Ida’s progressive views on mental health have had their eugenic elements airbrushed out, and wards on the site went on to become centres of excellence caring for and rehabilitating people with learning disabilities. Now the NHS is selling the land so that the wards can be demolished to make way for private housing and a private nursing home. This speaks volumes about a prevalent eugenic disdain for those who find themselves weak and undesirable in the face of what Wilson aptly calls the “survival of the richest”, echoing the term “survival of the fittest”, coined by Herbert Spencer.

*Editorial note: Galton did not in fact advocate the elimination of the “weak and undesirable” but rather proposed measures to encourage the reproduction of “individuals who bore the signs of membership of a superior race” (quotation from Inquiries into Human Faculty)

Francis Galton by Gustav Graef

Gerry Dorrian, a historian and philosopher, writes from Cambridge

A depressingly PC misrepresentation of Darwin and Galton, and almost as worthless as his unoriginal error-ridden pot-boiler on Hitler. His biographical attempt at Jesus had a just few fresh insights, but he has become a rubbish writer since his excellent studies of periods in British history. As Our Beloved President would tweet, “SAD!”

Mainstream eugenics was never about getting rid of existing disabled people, but getting rid of disabilities from future people. Galton had to rebuke Shaw publicly about this. It had supporters across the political and religious spectrum before, during and quite long after the Nazi years.

I see American Renaissance has just been (unreasonably) banned from Twitter and Amazon now has its Index Librorum Prohibitorum. We know that Wikipedia has a team of graduate “editors” to keep it kosher.

The purge of all websites with “white nationalist”, “revisionist”, “racist” and “sexist” content has begun, and “Social Darwinism” could follow.

Support Spiked-On line.

I see American Renaissance has just been (unreasonably) banned from Twitter and Amazon now has its Index Librorum Prohibitorum. We know that Wikipedia has a team of graduate “editors” to keep it kosher.

The purge of all websites with “white nationalist”, “revisionist”, “racist” and “sexist” content has begun, and “Social Darwinism” could follow.

Support Spiked-Online.