Gustave Doré, The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner

Alone on a Wide, Wide Sea

Review of Billy Budd, opera in two acts, music by Benjamin Britten, libretto by E M Forster and Eric Crozier, conducted by Ivor Bolton, directed by Deborah Warner, Royal Opera, 23rd April 2019, reviewed by Leslie Jones

The plot of Billy Budd hangs, no pun intended, on a somewhat implausible detail. Three sailors, including Budd, played by the excellent baritone Jacques Imbrailo, have been press-ganged from a merchant ship. It is 1797, during what Captain Vere of HMS Indomitable calls the “difficult and dangerous days”, following the naval mutinies at Spithead and the Nore, that “floating republic”. Billy, now a foretopman, sings farewell to his former shipmates on the Rights o’Man. Master-at-arms John Claggart (Brindley Sherratt, suitably sinister) takes this as an endorsement of Thomas Paine’s incendiary tome the Rights of Man. He persuades the repellent Squeak, a ship’s corporal, to spy on Billy.

“Life’s not all play upon a man-of-war”. Evidently not, with flogging for minor misdemeanours, such as slipping on deck, as in the case of the hapless Novice (Sam Furness). Bloodied and bruised, he can then only crawl across the stage. The remarkable libretto by EM Forster and Eric Crozier is replete with ironic observations, including Vere’s contention that the French “want all the world to be slaves”.

Michael Levine’s ingenious set, consisting of three hanging platforms, with ladders, ropes and sails, emphasises the contrast between the opulence of Captain Vere’s airy quarters, with its books, carpet and tin bath and the squalor and claustrophobia endured by the men below. Billy Budd is a universal parable about oppression. Feltham Young Offenders Institution, take note.

Critic Rupert Christiansen, in a review of an earlier production of Billy Budd at Glyndebourne, discerns in Claggart “a distorted physical lust compelled to destroy what it cannot possess” (The Daily Telegraph, 11th August 2013). Indicatively, Claggart’s nickname for Budd is “Beauty”, while other members of the crew dub him “Baby”.

For all his erudition and good intentions, Vere (Toby Spence, in fine fettle) remains a prisoner of pernicious rules and regulations. He knows that Claggart is evil and that Billy, a Christ like figure, is good. But he cannot save him. Director Deborah Warner, however, is unsure of the distinction between good and evil. She considers Claggart “a fallen angel” (see her uncompelling comments in Music Matters, Radio 3, 22nd April, and in “Staging Britten”, Official Programme).

In a beautiful gesture before going to his death, Budd blesses Captain Vere, hitherto “lost on the infinite sea” of uncertainty and unbelief. He thereby saves and redeems him. As E M Forster remarked in a letter to Britten, “Billy is our saviour, yet he is Billy, not Christ…”

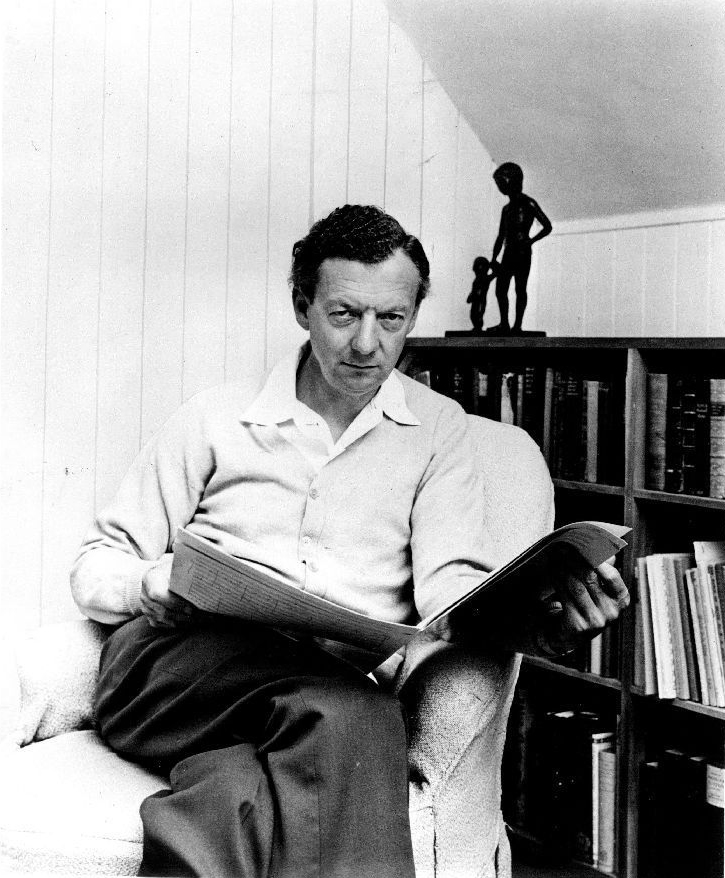

Benjamin Britten, London Records 1968

Dr Leslie Jones is Editor of QR