Broken Myths, Broken Landscapes

Broken Myths; Charles Sheeler’s Industrial Landscapes, Andrea Diederichs, De Gruyter, 2023, Berlin/Boston, Pb 267pp, reviewed by Leslie Jones

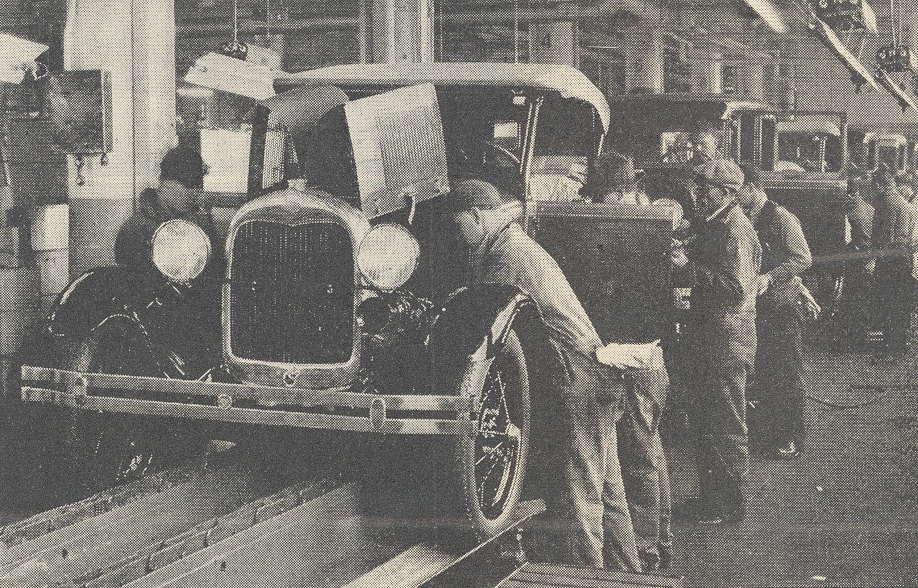

By 1927, the market share of the once mighty Ford Motor Company had shrunk from 50 to 15%. Rebranding was evidently in order. If you won’t change the product, change the perception of it. The Philadelphia advertising agency N W Ayer and son, accordingly, commissioned freelance photographer Charles Sheeler to take a series of shots of the recently opened River Rouge plant in Dearborn where Ford’s ‘new’ Model A was being produced. Fashion, Firestone, cameras, typewriters – all had hitherto been grist to Sheeler’s mill. His brief now was to help Ford “regain [its] former status as market leader”. He produced 33 photos which were featured in ten issues of Ford News.

In his Principles of Scientific Management (1911), Frederick Taylor envisaged what the author terms “a perfect man-machine symbiosis”. Time and motion studies were employed by Taylor’s team to ascertain the quickest, most efficient method of performing any given task in a factory. Workers were viewed by Taylor as “predictable, machine-like objects”. His overriding goal was to reduce costs and thereby maximise profits. Work should be speeded up and the work force subject to an enhanced division of labour. In effect, the worker would be de-skilled and expertise transferred to the machine. Taylor thought that higher wages would compensate for any resulting boredom and fatigue.

Henry Ford’s introduction of the assembly line in 1913 put Taylorism into practice à outrance. Parts were standardised and made inter-changeable. Workers were monitored and restricted to performing simple, repetitive, “mind numbing” tasks. The days of skilled workers ferrying tools and parts to different work stations were over. Workers became mere minders (adjuncts) of all powerful but obedient machines which dominated the production process. Andrea Diederichs (Trier University) maintains that although production was thereby increased and costs lowered, work became an irksome physical ordeal in this “new climax of dehumanisation”. She notes that Henry Ford required submissive, unskilled workers, whom he regarded as “replaceable and interchangeable at any time”. And that absenteeism and a high turnover of labour were engendered by monotonous work that according to sociologist Thorstein Veblen was “beneath the dignity of able-bodied men”. In 1914, indicatively, Ford bought off his disgruntled work force by introducing the 5 dollar day.

Hostility to corporate capitalism, in particular to ‘Taylorism’ and ‘Fordism’, has been extended to those who promoted its products. Sheeler is considered “the founder of the iconography of the machine age”, and responsible for the “aestheticization of Ford Motor co”, indeed for “the glorification of the machine”. The author, however, challenges the consensual view that Sheeler was uncritical of assembly-line production or that he idealised “the architectural and technical emblems of success”. She contends that although not permitted to photograph the assembly line itself (presumably because it would have revealed “the harsh reality of assembly line production”), in his 33 photos of the River Rouge plant, the factory operative is “reduced to the status of a machine minder”. The alienation of the worker identified by Marx in Das Kapital had reached its apogee. He was now what Arwen Mohun called “the prosthesis of the machine”

In Blast Furnace at Ford Rouge Plant (1927), a massive blast furnace “dominates the entire image”. The “miniscule figures of workers”, “small cogs within this gargantuan process”, “only become visible upon close inspection”. In Stamping Press – Ford Plant (1927), likewise, Sheeler presents “the decisive shift that the human labour force has undergone as a result of increasing mechanisation”. In Forging Die Blocks – Ford Plant (1927), the workers, for once, are highlighted. Yet they still only service an all powerful machine. Workers are generally depicted as dispensable, de-individualized, “ant-like subjects’ who are either idle or “servants of gigantic machines”, as in Storage Bins at the Boat Slip at Ford Rouge Plant (1927) and Cranes at the Boat Slip – Ford Plant (1927). Diederichs concedes that Sheeler aestheticized industry, that he posited “the grandeur and majesty of the work” at Ford Rouge plant. But she contends that he also showed “the working reality of the people employed there”, in particular their “subordinate hierarchical position”.

Sheeler subsequently produced four oil paintings depicting the River Rouge plant, most notably American Landscape (1930). Mark Rawlinson maintains that they concealed the truth about capitalism. But Diederichs, as in her aforementioned analysis of the photos, proposes in this compelling exegesis that these artworks “bear witness to [both] the achievements and ambiguities of progress”.

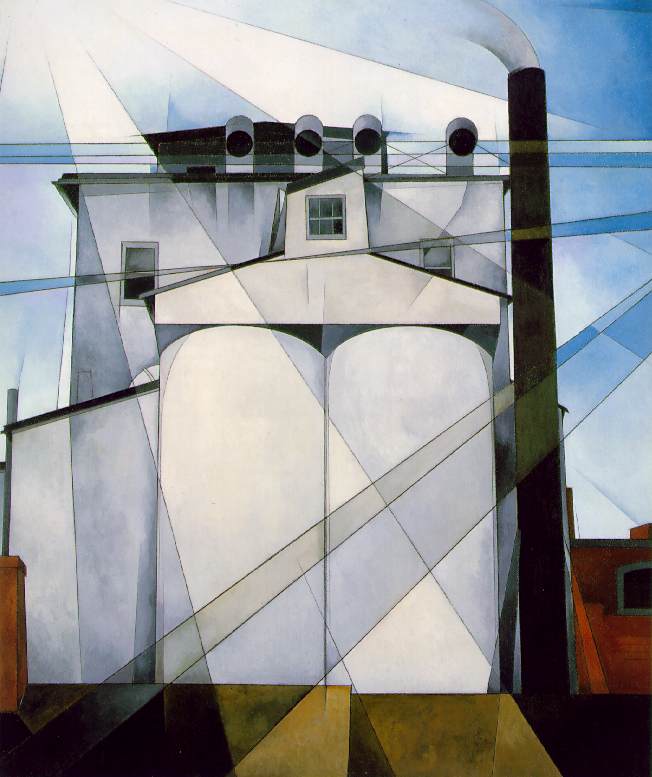

Charles Demuth, My Egypt, credit Wikipedia

What a thought-provoking piece.

I remember seeing a photograph on a recent TV programme about British industrial decline, of the huge railway works at Doncaster ~ in the early-20th-century heyday of steam. The same landscape, from the same perspective, was then shown, taken in the present day: a brownfield site of nothingness, and hardly a single feature that would tell you that a vast delta of sidings and sheds had been there. What has happened to the descendants of all the men who worked every day in that town of railways? What happens when work (and the moral side of work) vanishes?

Who owns General Motors, IBM, Microsoft Corp, Uber, “British” Steel, Sotheby’s?

Land of hopeless “Tories”

Goggling at TV

How can we restore thee

Unless our speech is free?

Wider, yet still wider

See the bankers set,

The real almighty

Behind our national debt.

So why not double current investment from the Chinese Communists to £300 billion, including nuclear energy, surveillance equipment, transport, cyber communication, supermarkets and education?

Complete the wonderful HS2 asap?

Bring here all those unemployed youngsters from Africa and turn them into whizz-kids by maths lessons till they are 18+ (teenage Somalis especially should be given a stab at this)?

Legalise all recreational drugs and make huge profits – the Vietnamese and Albanians can lead the way?

Enjoy the benefits of Brexit by letting the EU look after Scotland, Northern Ireland and hopefully Wales?

Turn Buckingham Palace into the Biggest Mosque in the West, and charge the pilgrims and tourists?

Just a few ideas….

In the same section as yet another article from Hamish “Pangloss” McRae telling us that things can only get even better, the Financial Mail on Sunday (15 January 2023) reports that the so-called National Security & Investment Act to protect against foreign predators in sensitive sectors, like defence and energy, has been used to block only five deals out of hundreds screened, quoting for instance recent sale of an important semi-conductor company to an investment vehicle partly controlled by the Communist Chinese dictatorship.

The flow of British research and invention to overseas competitors, tyrannies or enemies has always been a problem, but the transition of a great nation into a helpless zone drained by foreigners, owned by foreigners, controlled by foreigners and eventually occupied by foreigners is a future to which only a xenophobic white supremacist race hater could possibly object, and sooner or later should be silenced by “any means necessary”.