Book Reviews

by QR Reviewers

……..

………….

Meet the Ancestors

Ed Dutton enjoys a fascinating memoir

My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers Her Family’s Nazi Past . . . by Jennifer Teege and Nikola Sellmair. Translated by Carolin Sommer. 2015. Hodder and Stoughton. Hardback. 221pp.

Over the last twenty years, a niche genre has developed in German popular literature: the relatives of senior Nazis pen their own autobiographies, focused on how their family dealt with the shame of being descended from prominent Hitler-supporters, how the authors feel about it, and how they have attempted to make amends for the crimes of their ancestors, for which they hold some hereditary guilt. A couple of these, such as The Himmler Brothers, by Himmler’s great niece Katarin Himmler, have been translated into English. The lives and feelings of these Nazi descendants seem to make compelling reading. We are impressed by those who have interesting ancestors, yet vaguely aware that personality is partly genetic. As such, the descendants of eminent Nazis both attract and repel us. They provoke our hope (perhaps their ancestors’ actions were mainly a function of environment) and our fear: maybe they were essentially a function of genetics. The authors struggle with the same hopes and fears. These are exciting combinations for a popular book.

Jennifer Teege’s newly translated autobiography My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me is, in many ways, more compelling than others in this genre, not least because the author is mixed race. Half German and half Nigerian, Teege’s mother was a mentally unstable and dysfunctional woman who subsequently married an abusive husband. Born in 1970 in Munich, Teege was raised in a Catholic children’s home until the age of 3, having semi-regular contact with her mother and her mother’s mother until the age of 7, when she was adopted by her educated, white foster family who then stopped her biological family from keeping in touch. When she was 20, her half-sister, by the abusive father, tracked her down and she ended-up meeting her biological mother, but there was no great bond between them and they lost touch.

Then one day, when Jennifer was 38 and married with children, she was in Hamburg Library when she happened to pick up a book called, I Have to Love My Father, Don’t I? by Monika Goeth. Looking through it, she realised that this was her biological mother. In fact, she recalled that she was once ‘Jennifer Goeth.’ Reading the book, she made a horrifying discovery. Her grandmother, whom she recalled with affection, had been the common law wife of Amon Goeth, commandant of the Plaszow concentration camp. This was no ordinary German war criminal. This was the commandant who had been portrayed, only a few years earlier, by Ralph Fiennes in Schindler’s List; the one who shot Jews from his balcony for fun; the so-called ‘Butcher of Plaszow.’ This revelation sent Teege, who we later discover had long suffered from mental illness anyway, into a long depression in which she obsessed with discovering everything she could about her grandfather. She goes on pilgrimages to former Nazi concentration camps in Poland and become wracked with guilt about the actions of her infamous ancestor.

The book is divided into two interspersed narratives, which is confusing at first but the benefits eventually become clear. On the one hand, there is Jennifer’s memoir, centred around the discovery of her forebear. Much of this is written in the present tense, as if she’s going through it all again as some kind of regression therapy. Then there is the broader historical narrative, written by her co-author, which includes interviews with Jennifer’s friends and relatives. This contrast eventually works quite well, meaning that neither part of the book becomes stale. It also means that the book genuinely presents Jennifer’s own words, rather than those of a ghost writer.

It seems unlikely that Goeth would have shot his grandchild. Jennifer’s assertions that this is so dismisses any attempt to understand Amon because his last words (before being hanged on the third attempt) were ‘Heil Hitler.’ However, this rather contradicts her later emphasis on the importance of blood to love. It is likely that her grandfather would have loved her, evil as he was to those outside his in-group. The translator has also chosen to make the title more emotive than the German version, which was merely ‘Amon’ and then the main title used in the English version.

But, overall, the autobiography is fascinating reading, even beyond the author’s discovery and its psychological aftermath. Jennifer’s insights into how it feels to be raised in a children’s home and how it feels to be an adopted child, especially a mixed race one adopted into a white family who already have two of their own biological children, are informative and poignant. She insists that you not only feel unwanted (as you have been given away) but you know that your adoptive parents, deep down, are bound to love their own children more than you. You feel, constantly, that you must earn their love and that it cannot be taken for granted. You are likely to be in the intellectual shadow, she explains, of your parents and their biological children. She observes that children such as her tend to suffer from mental illness and strongly rebel as teenagers, making this biography potentially invaluable, in that mixed race adoption appears to be a growing phenomenon. Teege, though perhaps slightly self-absorbed at times, is also an intriguing woman, independent of her circumstances and family tree. Before she knew about anything about Amon Goeth, she had lived in Israel, learning fluent Hebrew and obtaining a degree, taught through Hebrew, from Tel Aviv University. Her memories of life in Israel are very readable, and she ruminates, years later, over how to break to her Israeli friends whom she has discovered she really is. Interestingly, they comment that it would have been difficult to be her friend had she known (and told them about) her grandfather when she was in Israel.

This is a thought-provoking book that is well-worth reading both as examination of how it feels to descend from a notorious Nazi and of what it is like to experience interracial adoption.

Dr Edward Dutton is Adjunct Professor of the Anthropology of Religion and Finnish Culture at Oulu University

………….

…….

Nazi Germany, some conflicting perspectives

Richard Evans rounds off his recent contribution to Third Reich studies

Richard J Evans, The Third Reich in History and Memory, Little, Brown, London, 2015, 483 pp, £25

The Third Reich in History and Memory is a collection of previously published essays, predominantly book reviews. As its author Richard Evans remarks in the preface it constitutes an unofficial report on significant shifts in perspective concerning Nazi Germany over the past fifteen years. And, we might add, an examination of certain key issues in this field, notably the question “was the Holocaust unique?”

Sir Richard notes in chapter 7, entitled “Coercion and Consent” that a consensus emerged amongst historians in this period that Nazi Germany was a political system that enjoyed widespread popular approval. In Fascist Voices (2013), also reviewed herein (chapter 15, “Hitler’s Ally”) Christopher Duggan adopted a somewhat similar line apropos Mussolini’s regime (see my review of Fascist Voices at www.quarterly-review.org/?p=2246).

What has been called the “voluntarist turn” in Nazi studies entails the thesis that support for the regime was freely given by many Germans. Some historians contend that the idea of a “people’s community” (Volksgemeinschaft) enjoyed widespread support after the “chaos of the Weimar years” (Evans page 125). In Life and Death in the Third Reich (2008), historian Peter Fritzsche underlined the fact that by the mid1930’s only about 4000 political prisoners remained in concentration camps. (He failed however to mention the 23,000 political prisoners in Germany’s state prisons and penitentiaries).

The theory that Nazi Germany was a “dictatorship by consent” or Zustimmungsdiktatur was based on three main premises; first, that the Nazis won power legally in what Karl Dietrich Bracher calls a “legal revolution”; second, that Nazi terror and repression, including incarceration in concentration camps, mainly affected minorities, notably social outsiders, such as communists (sic), criminals, the mentally and physically handicapped and vagrants; and third, that the popularity of the regime was repeatedly demonstrated in national elections and plebiscites.

Professor Evans, however, both in this current volume and in his trilogy of books on the Third Reich, has consistently highlighted the role of violence and repression in the establishment of the Nazi regime and its dictatorial and manipulative elements thereafter. He upholds a Marxist, class warfare perspective on the Nazis’ consolidation of power, emphasising the destruction of institutions associated with the proletariat, notably the Communist and Social Democratic Parties and the trade unions. He emphatically dismisses the notion that the majority of Germans were not affected by coercion or repression. As he points out, in the Reichstag Elections of November 1932, the Social Democrats and Communists, mass parties whose officials were subsequently subjected to draconian measures, won 13.1 million votes compared to 11.7 millions for the NSDAP.

As regards the putative popularity of the Nazis as evidenced by elections etc, Evans notes that in the 1934 plebiscite on Hitler’s appointment as Head of State and, again, during the plebiscite in April1938 on the Anschluss, gangs of storm troopers marched voters to poll stations where they usually had to vote in public. The institutions involved in the coercion of the German population included not just the Gestapo but also the SA (3 million strong by 1934), the Courts, the police and the prison system plus the ubiquitous block wardens of whom there were 2 million by 1939. Potential trouble makers amongst the work force could be compulsorily reassigned to work in war related industries far from home. The threat of withdrawal of welfare benefits was another means by which opposition to the regime was neutered.

From interviews of elderly Germans carried out in the 1990’s by Eric Johnson and Karl-Heinz Reuband (who, like Robert Gellately, maintain that Hitler and National Socialism were immensely popular) Evans infers that support for the regime was strongest amongst the younger generation growing up in the Nazi era and exposed to constant indoctrination in school and in the Hitler Youth. People who had reached adulthood before 1933, however, were more resistant to such indoctrination. Former supporters and members of the Catholic Centre Party (wound up in 1933 after unremitting intimidation by the Nazi Party) provide a telling example. One time Communists and Socialists were also relatively unreceptive to the regime’s propaganda.

These facts give the lie to Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s characterisation of the German people in Hitler’s Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust as predominantly anti-Semitic.

But why, given all this underlying potential opposition to Hitler, was there no popular revolt against his regime especially once it became clear that Germany was heading for defeat? Evans points out in this context that during the war executions in Germany reached the figure of 4 to 5 thousand per year and that 30,000 troops, likewise, were executed by firing squads. Contra Fritzsche, he detects the influence of Goebbels in the supposedly spontaneous demonstrations of support for Hitler in July 1944 after he survived Stauffenberg’s attempt to assassinate him.

The supposedly unique status of the Holocaust is another recurring theme of The Third Reich in History and Memory. In his influential volume South-West Africa under German Rule 1894-1914 (1968), historian Helmut Bley described the German war against the Herero and Nama tribes in Namibia (1904-1907). In some respects, this was a dry run for the Holocaust, with summary executions, incarceration in concentration camps, women and children left to starve, forced labour and laws forbidding racial inter-marriage.

The deliberate attempt to exterminate the Hereros unquestionably constituted genocide, in Evans’ estimation. Ditto some other notorious historical episodes such as the Armenian Massacres and the Ukrainian famine of the early 1930’s or Holodomor. The Soviet authorities also killed or deported or imprisoned large numbers of the Polish elite in Poland’s eastern provinces. At the end of World War Two, the Germans of Eastern Europe (like the Poles before them) experienced ethnic cleansing (expulsion and forced migration) on a massive scale with the usual accompanying atrocities.

Yet the Holocaust still remains sui generis, in Evans’ judgement. Only the Nazis killed people solely because of their alleged racial identity and characteristics. And as Max Hastings has observed in his review of Mark Mazower’s Hitler’s Empire (New York Review of Books, October 23, 2008) “the economic cost to the German war effort of the Final Solution and the Nazis’…efforts…to reshape Eastern Europe” were considerable. From a military and economic perspective, such policies “represented madness”.

According to Germany’s “General Plan for the East”, 85% of the Polish population and very large proportions of the Slavic populations throughout German occupied Eastern Europe would be left to die of hunger and disease. But whereas the Slavs, like the Hereros before them, were considered sub-human, merely an obstacle to German expansionsm, International Jewry was regarded as a threat to Germany’s very survival, as the “world enemy” or Weltfeind. The Jews were accused of fomenting socialist revolution in Germany in 1918 (the so called “stab in the back”) and of ultimately controlling Bolshevism in Russia and capitalism in the United States, countries which both supposedly posed an existential threat to the Third Reich.

At this point, however, one criticism – being left to starve by the Soviet Communists because you are ascribed to an allegedly parasitic class, the kulaks, comes to much the same thing as being shot in a ditch by the Einsatzgruppen because you belong to an allegedly inferior race. Dead is dead. Can were detect in Evans’ reflections on the uniqueness of the Holocaust some lingering notion that State Socialism was more progressive than National Socialism? But this is our only reservation about Professor Evans’ otherwise impeccable analysis.

Reviewed by Leslie Jones

©

Dr Leslie Jones is Editor of QR

……..

……………

The “Flying Salzburger”

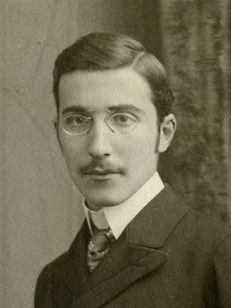

Stoddard Martin considers the enigma that was Zweig

Among German-language authors of the first half of the 20th century Stefan Zweig is now being re-positioned near the top. Some contemporaries saw him as in ‘the first rank of the second rate’, to use Somerset Maugham’s self-deprecation; Hugo von Hofmannsthal, whom Zweig briefly succeeded as Richard Strauss’ librettist, put him several rungs beneath that.[i] In the moments of depression which darkened his later years Zweig may have seen truth as well as envy in such relegation. He was lucky however to have huge numbers of admirers, a public which bought his books in the hundreds of thousands, fellow humanists who shared his ideal of a finer pan-European order and above all an adoring young second wife, who followed him in a restless search for a final resting-place and finally joined him in suicide there.

From a literary point of view Zweig belonged to the last great era before writing was overtaken by other media as a principal means of telling stories and promulgating ideas. From a political point of view he belonged to a last gilded age before world war disfigured Europe. Child of privileged Jews in fin-de-siècle Vienna, he was one of its most famous sons by 1920 when with a fellow-writing first wife he decamped for a hill over Salzburg. There he busied himself on the novellas and plays such as he had churned out since his early twenties. He worked indefatigably, travelled peripatetically and cheated on his wife shallowly. In a life devoted to the written word, he was a manic collector as well as a producer. He gave public readings and lectures about culture far beyond his imploding Germano-phone sphere. And as his fame spread, his tendency deepened to explore of acts of danger, daring and will.

He wrote mini-biographies of great men – Balzac, Dostoyevsky, Nietzsche – building them into the popular Baumeister der Welt series, based not so much on research as on analysis. He sought to discover what he called the lebenskurve and in effect to create literary-historical equivalents to the psychological case-studies being written by his friend and fellow Viennese Sigmund Freud, a reluctant inclusion among his subjects. Analysis of great men morphed into pinpointing crucial moments, the Sternstunden as Zweig called them, on which history pivots. High-risk explorations, visionary inventions, inspiration via mass emotions, creativity against physical odds, vain leaps after fortune, persistence in the face of defeat… Zweig zeroed in on the obstacles he saw men as having to face if mankind as a whole were to move forward: Balboa in sighting the Pacific, Scott in the Antarctic, Lenin in Petrograd.

One can hardly read of these heroic cruxes, all in the present tense, and not feel Zweig’s febrile excitement. He was a man in a hurry in an age which had an appointment with destiny. His vignettes, full of hope of beating the odds, were also haunted ever by spectres of downfall. Rouget de Lisle composing ‘The Marseillaise’, Grouchy’s lack of initiative at Waterloo – Zweig had vast interest in upheavals of the previous century and naturally sensed that in a few years’ time some of his readers might be burning his books. Anxiety stalked, but he did not let it impede the drive of his prose or choice of his topics, which belonged to the frightening Zeitgeist. Like Freud, this child of Austro-Hungary reviled Woodrow Wilson for ‘the failure of Versailles’. He grew as ardent in promoting pacifism and European union as malign contemporaries were in inciting war and race hatred. Hitler was a contemporary compatriot. Goebbels and Rosenberg read his books. Suicide with younger wives would happen in the Berlin bunker too. Victim and victimizer came from contiguous milieux.

In fiction Zweig specialized in the long story and wrote only one novel. Like his Sternstunden, his collected tales have recently been made available in English by the elegant Pushkin Press. Cloth-bound and printed on good paper, with decorative colophons to demarcate the text, these books are objects that the bibliophile Zweig might have approved. And the tales match their covers in quiet smartness, with a variety of styles and subjects including something to seduce a life-savvy aunt as well as wide-eyed boys. Like Maugham, Zweig had a knack for narration and a feel for human nature; yet unlike that often spiteful ironist, he had a suffering soul. Hard hearts may accuse him of sentimentality, but few now will be able to read ‘In the Snow’ – a Jack London-like tableau of the population of a ghetto freezing to death when fleeing pogrom – without appreciating the prescience of this carpet-slippered son of Vienna to the catastrophe others of his kind were shortly to undergo.

By the mid-1930s Zweig was in full flight from the arrival of the mad expressionism of National Socialism, with which his overwrought style and enthusiasms had aspects in common. In a book recently published about his last years, George Prochnik does not flinch from recognizing such ironies. The Impossible Exile shows Zweig as a figure in whom the disease of the age was ever apparent, and never more so than at his end. Where in a world beset by furies could an individual of devout European culture turn? London took him, for a time; he retreated to Bath, tried to idealize it but eventually found English sang-froid insipid. New York took him, also for a time; he retreated to a quaint hamlet on a bluff overlooking Sing-Sing but found it a prison. America enjoyed bounty while Europe convulsed in war and its citizens starved. Zweig, rich from both inheritance and book sales, was beleaguered by indigent fellow-refugees wishing introductions, begging cash. On top of it all, where in the U. S. could one find a proper café, that institution so central to Viennese cultured life?

If the detail sounds banal, it is crucial to the tale Prochnik tells. For it is not just Zweig in exile whose plight he analyzes but the condition of flight from Hitler’s Europe altogether, especially for Jews who in a few generations had gained and now were losing the splendeurs et misères of high civilization. Where to go, who to be, what language to write in? One may have been ‘saved’ – that is, to have found shelter in the United States – but what then? The world they knew had vanished. They wandered hither and thither, haunted, bickering with one another, hating while at the same time being obliged to love where they had come to. Zweig’s solution? to penetrate further into new worlds, another land of the future – Brazil. Nature in the hills overlooking Rio was gorgeous, the coffee to die for. And that was it. Fully cut off. Utter deracination. At age sixty, the man was played out. And worse tragedy, whose promptings can never quite be known, is that his young wife should like some Brünnhilde of mythic opera have chosen to cast herself into this personal Götterdämmerung with him.

The finale has caused much speculation: Laurent Seksik published a novel about it in French in 2010, now available in English from Pushkin and as graphic text from Salammbo. The latter makes Zweig’s story accessible for those who are unlikely to read his massive oeuvre or more challenging works proliferating about him[ii]. Whatever the dominant motive for his melodramatic end, the novel musters its probable elements: his exhaustion, his wife’s asthma, the melancholy of exile, horrors engulfing those of his kind left behind, a killing nostalgia, temperamental allergy to the new and a bourgeois mittel-European fragility in face of carne-val masses… The pagan new age birthed no ‘terrible beauty’ for Zweig. It was no ‘country for old men’ in either metaphysical or physical senses. Suicide is a pathetic response, however, and surely no country for a loving young wife. On the basis of the evidence, it is hard not to construe that the great writer was at his exit neither a worthy exemplar nor a responsible husband. But let us be kind. His end, like London’s[iii], was above all a Faustian price to be paid for having poured out popular books of brilliance year after year.

ENDNOTES

[i] Hofmannsthal called Zweig sixth-rate, as Oliver Matusek reports in his biography Three Lives, which I reviewed in a more extensive essay on Zweig for QR at the beginning of 2013

[ii] Such as Rudiger Görner’s excellent critical study, published by Sonderzahl but not available in English, discussed in an extensive note to the above-mentioned essay

[iii] I have in mind the sudden death of the exhausted Jack London, which many believe to have been by his own hand. The suicide of other played out writers of Zweig’s period and after comes to mind too, those haunted by the Auschwitz spectre such as Primo Levi and others who simply couldn’t face loss of powers such as Ernest Hemingway

Books under review:

Shooting Stars: The Historical Miniatures, trans Anthea Bell (Pushkin, 2013)

The Collected Stories of Stefan Zweig trans. Anthea Bell (Pushkin, 2013)

The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World, George Prochnik (Granta, 2014)

The Last Days of Stefan Zweig, Laurent Seksik with Illustrations by Guillaume Sorel, trans. Joel Anderson, adaptation Kelly Smith (Salammbo, 2014)

Stoddard Martin is an author, publisher and academic.

This article is adapted from material published in the Jewish Chronicle

…….

…………

Weber’s Epigone

Bill Hartley considers a curious contention

Early Islam and the Birth of Capitalism, Benedikt Koehler, Lexington Books, London 2014, 212pps

The Prophet Muhammad was a businessman and entrepreneur. This is one of the many interesting facts revealed in Benedikt Koehler’s book. Indeed, Koehler has the Prophet fully immersed in the business world of his era before spiritual matters took precedence. In addition to this he tells us that early Islam created a single market, encouraged entrepreneurship, promoted the property rights of women, religious minorities and foreigners. According to the author, the Islamic world was the creator of financial instruments that we take for granted today, such as charitable trusts and tax exemptions. To the 21st century reader it begs the question; when did it all start to go wrong?

Apropos capitalism, Koehler emphasises the comparative economic under development of Europe. He also suggests that because there was no literature of consequence on economics bequeathed by Rome nothing much was happening there either. However one can infer a great deal about economic activity in the Roman Empire from a study of its legal system. Roman contract law was very sophisticated suggesting that it had evolved to underpin and regulate business activity.

These caveats aside, Early Islam does cast light on the commercial life of Arabia during this period and reveals a sophisticated civilisation which had been trading with the wider world long before Muhammad’s birth in 570.

The book is at its best when Koehler considers how the geographical position of Arabia allowed it to trade with China and across the Peninsula to Byzantium and the Levant. Particularly interesting are the short sketches covering trade with Italian city states such as Venice and other maritime republics plus the use of the commenda or convoy system for speculators to fund and equip ships in profit sharing enterprises. These were essentially a maritime version of the camel trains which moved in and out of Mecca.

Yet ultimately I was unconvinced that early Islam was the originator of many of the commercial devices familiar to us today and I suspect that those with a knowledge of Ancient Rome and Egypt could make similar claims. Human ingenuity being what it is there was an obvious incentive to find ways of making commerce easier. The presence of a legal system to help regulate trade is as powerful an indicator as writings on economics.

The characterisation of Muhammad as a businessman begins to unravel when the book moves seamlessly into a description of his ability to run successful raiding parties. The author may seek to add a veneer of commercial respectability to this sort of activity with terms such as ‘managing logistics’ and ‘setting incentives’ but I believe the correct term is somewhat different. On the same subject, ‘performance related payments’ equates to dividing up the loot.

Two final criticisms – an aspect of the book which definitely did jar was the author’s use of modern business language. Terminology changes rapidly in the corporate world and what seems fresh and immediate now may soon become hopelessly dated. Most economic historians accordingly avoid using the latest business terms. Finally there was scarcely any mention of the slave trade, which I believe was an Arabian “niche activity”, as we would say today.

William Hartley is a freelance writer from Yorkshire

…….

………….

Inside Putin’s Russia

Frank Ellis reviews a timely but one-sided account

Peter Pomerantsev, Nothing is True and Everything is Possible: Adventures in Modern Russia, Faber & Faber, London, 2015, ISBN 978-0-571-30801-9

Unlike Anne Applebaum, who is cited on the rear cover and describes this book as ‘electrifying’ and ‘terrifying’ and Tina Brown, the glossy-mag queen, telling the world that Pomerantsev’s book was ‘a riveting portrait of the new Russia’ and that she ‘couldn’t put it down’, I was not entirely overwhelmed. Bits of interest and humour there are but much of what Pomerantsev has to say could have been condensed into a short article. For reasons which are not clear to this reviewer the title of what I shall assume is the same book in terms of content but published in the US is given as Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia. In view of the fact that language and media manipulation is one of the main charges of which Pomerantsev accuses the Putin establishment, two different titles for the same content strikes me as an example – albeit minor – of the very same thing. The first part of the book title is also irritating. It may be intended as some deliberate marketing contradiction to grab attention but if nothing is true why should I believe anything Pomerantsev or his interviewees have to say, and is the statement that “nothing is true” itself true or is it a lie?

A central theme in Nothing is True is the grotesque behaviour of exceptionally wealthy Russians and gangsters. Now the grotesque is also a major theme in Russian literature, found, for example, in the works of Nikolai Gogol (Dead Souls, 1842 & The Overcoat,1842), Fedor Dostoevsky (The Double, 1846, Notes from Underground, 1864, The Devils, 1871-1872) and in the twentieth century, in the works of Mikhail Bulgakov (The Master and Margarita, 1966-1967), the magnificent Vladimir Voinovich (The Life and Extraordinary Adventures of the Soldier Ivan Chonkin, 1975 & Monumental Propaganda, 2001), Andrei Platonov (The Foundation Pit, 1987) and Viktor Pelevin (Life of Insects, 1993 & Chapaev and the Void, 1996). References to some of these works would have provided the freakery of modern Russia with a definite historical-cultural context, since the appearance of quacks, extremist politicians, pseudo-Russian Orthodox fruitcakes, false pretenders, born-again holy fools, political fixers, pious Hell’s Angels with a mission to save Russia from Satanic, Western influences, Stalin worshippers and drop-dead gorgeous girls determined to get their hands on – or more accurately to get their legs and lips around – some super rich sugar daddy (known either as a Forbes or a sponsor) are what to expect in Russia. Mother Russia, God bless her, has no shortage of head cases. There is never a dull moment, unlike Sweden where the trees are known to perish from boredom.

The lack of detailed literary references in Nothing is True is important for another reason and one peculiar to Russia. In Tsarist Russia the writer was the voice of a largely silent majority; in Soviet Russia he was co-opted to be a socialist-realist engineer of human souls, extolling the Soviet state. In First Circle (1968), one of Solzhenitsyn’s characters, the soon-to-be arrested Volodin, tells a Soviet hack that a great writer is like having a second government. So any author that deals with the Russian media as it has developed for better or for worse since the mid-1980s must consider whether television and its anti-culture of toxic celebrity have now finally supplanted the writer as the cultural oracle. If this has happened in Russia or shows all the signs of accelerated transition, this represents a major cultural shift. These days would Russians read a Solzhenitsyn or Grossman or do they permit themselves to be hypnotised by talking heads?

Russians would certainly be entertained by How to Marry a Millionaire: A Gold-Digger’s Guide. The title of this Russian series speaks for itself. Girls are taught how to get their man or parts of him at any rate, and one of the hot tips given to them is that they should squeeze their vaginas tight, so as, apparently, to dilate their pupils and make themselves look more attractive.[i] When the girls want something from a Forbes they must follow the advice: look, nod and stroke.

There is something unsettling about the fate of these girls, especially the models. Two days before her twenty-first birthday, Ruslana Korshunova, committed suicide. Her name matches her beauty: Ruslana is a nod in the direction of Pushkin and Korshunova suggests the Russian word korshun, the kite, the bird of prey, a hint of freedom that was never hers, and unfortunately she was the prey. The most likely thing that prompted her to kill herself was that she fell into the clutches of an organisation, a cult, called Rose of the World. This organisation, messed with her head, to put it mildly, and it got too much for her, poor girl. Pomerantsev quite rightly calls these girls ‘the lost girls’. Despite all the international travel, the glamour and money, they lead a wretched existence: lonely, vulnerable and exploited by unscrupulous men and women. No wonder that so many commit suicide or suffer from extreme depression.

As far as Pomerantsev is concerned, post-Soviet Russia is a giant propaganda state in which the mass media in all their forms are controlled by the Kremlin. Thus, according to Pomerantsev, Ostankino is ‘the battering ram of Kremlin propaganda’.[ii] If, as Pomerantsev asserts, the task of Ostankino is to blend ‘Soviet control with Western entertainment’[iii] then perhaps Pomerantsev should explain the essential difference between Russian television and the degenerate prolefeed catering for semi-literate Western audiences in, say, the US and Britain.

Pomerantsev is also highly critical of Russia Today (RT), since, according to him, RT uses Westerners as a front for the Kremlin: ‘It took’, he says, ‘a while for those working at RT to sense something was not quite right, that “the Russian point of view” could easily mean the “Kremlin point of view”, and that “there is no such thing as objective reporting” meant the Kremlin had complete control over the truth’.[iv] Pomerantsev has obviously not been following the way the BBC has mutated into an aggressive, Goebbels-style propaganda organisation on behalf of the EU, multiculturalism, feminism and uncontrolled immigration, using its reach to attack and to vilify any person or organisation that opposes the sacred causes of the Neo-Marxist left. It seems to me that the growth and reach of Russia Today is a very good thing and some of its coverage of the Islamification of the West and the dire threat posed by mass immigration is what makes it so popular. Russia Today broadcasts topics that the BBC censors, distorts or passes over in silence because the overpaid BBC programmers are themselves terrified of, and hate, ‘objective reality’. The success of RT in challenging the US government’s propaganda machine also arouses visceral and real fear and loathing among US media controllers. This is evident from the fact that Andrew Lack, the head of the US Broadcasting Board of Governors, classifies Russia Today as ‘a major challenge’ along with IS and Boko Haram. Citing RT in the same breath as terrorist groups – the BBC refers to the delightful creatures of IS and Boko Haram as ‘militants’ – is no accident but a calculated attempt to smear a legitimate and highly effective media outlet (hence the smear) and to imply that the Russian Federation itself is a terrorist state or that it sponsors terrorism.

Russia, claims Pomerantsev, is not ‘a country in transition but some sort of postmodern dictatorship that uses the language and institutions of democratic capitalism for authoritarian ends’.[v] Really? Is this unique to Russia? Pomerantsev bemoans the influence of Vladislav Surkov, a so-called political technologist, essentially a propagandist, whose modus operandi is described as exploiting ‘democratic rhetoric’ but having ‘undemocratic intent’.[vi] This is all well and good but what is the difference between the media lying and manipulation encouraged and pursued by the Blair regime and actively continued and pursued by Cameron, never mind the agitprop spewed out by US TV channels and US government agencies?

The dictatorship of laws, decrees and statutes in Russia is not the same thing as the Rule of Law and Russia has a long way to go before it can be considered to be a state under the Rule of Law. However, it must be made quite clear that what was identified as the Rule of Law by Dicey in the nineteenth century and which emerged from a small island population may not be at all suitable for a state the size of Russia and especially one which has no long tradition of private property rights. Western ideas of the Rule of Law and liberal democracy, essentially English, can grow and develop over time, but they cannot be imposed. Disastrous wars and their aftermath in Iraq and Afghanistan confirm this point.

There are some interesting errors and omissions in Nothing is True. At the start of his book Pomerantsev claims that Russia has 9 time zones. 2 of the 11 zones were indeed eliminated in March 2010. However, this regime was abolished in October 2014, another 2 zones being created so taking the total back to 11. Another error concerns the transliteration and translation of the title of a major Soviet propaganda exhibition. Pomerantsev refers to the All-Russian Exhibition Centre (VDNH). It is in fact VDNKh – Vystavka dostizhenii narodnogo khoziastva – Exhibition of the Achievements of the National/People’s Economy. A more serious error or rather omission is that Pomerantsev bypasses completely the murders of Alexander Litvinenko, the former Russian agent, and

Anna Politkovskaya, the journalist. Both were murdered in 2006. It is one thing for the Kremlin to create its own version of the world according to Putin, the BBC and the US media provide much the same sort of service for their government masters, but it is another matter entirely when journalists are murdered in Moscow. Pomerantsev goes into great detail about the presence of wealthy Russians in London, relating the account of the court confrontation between Boris Berezovsky and Roman Abramovich, yet omits to raise the altogether far more serious matter of Litvinenko’s murder in London. Judging from his account Pomerantsev was in Moscow when Politkovskaya was murdered. Having been part of the Russian media establishment – and which, now back in London and getting chummy with the BBC, he attacks – he would have picked up all kinds of interesting rumours. Yet there is nothing from Pomerantsev. Why the silence? This is a general flaw since Pomerantsev’s coverage of the endemic gangsterism in Russia is also far too superficial, even flattering, whereas David Satter’s, Darkness at Dawn: The Rise of the Russian Criminal State (2003), is a brutally objective assessment and remains essential reading.

Pomerantsev’s presentation of the mass media in the Russian Federation does convey an impression of the surreal and absurd but one should not be fooled. Media control pursued by the Putin government is part of a two-fold riposte to what Russia’s leaders see, correctly in my view, as an aggressive US/EU-sponsored information war against Russia. The origins of this policy go back to the Doktrina Informatsionnoi bezopasnosti Rossiiskoi Federatsii (The Doctrine of Information Security of the Russian Federation) that was signed in to law by President Putin in 2000. The first element in this response is defensive. Hostile foreign influences in Russia cannot be totally excluded but the primacy of the Russian government’s interests can be asserted. The second element is aggressive and involves the promotion and projection of Russian interests and power. A major forum for this policy is Russia Today. The reason that Russia Today makes so much of the failure of Western politicians to counter the extreme dangers of Islam and the anti-white ideology of multiculturalism is because RT executives know full well that US and British media outlets actively and ruthlessly suppress (censor) the truth and thus provide RT with an opportunity to champion the truth and to expose Western mendacity and hypocrisy. During the Cold War Russians listened to Western radio – Voice of America, Radio Free Europe, the BBC and Deutsche Welle – to find out what was happening. These days, Westerners who see through the organised Orwellian lying of their national governments, their corrupt state media agencies and the quasi-fascist European Union are far more likely to get an accurate account from the former Cold-War enemy. History is indeed a cunning old bastard.

© Frank Ellis, 2015

Frank Ellis is an historian and the author of The Stalingrad Cauldron (2013). His new book, entitled Barbarossa: Sunday 22nd June 1941, will be published later this year

[i] Nothing is True, p.15

[ii] Nothing is True, p.6

[iii] Nothing is True, p.7

[iv] Nothing is True, p.56

[v] Nothing is True, p.50

[vi] Nothing is True, p.77

……

…………

Fantasy Racism

Henry Hopwood-Phillips peruses a provocative exegesis

Adrian Hart, That’s Racist! How the Regulation of Speech and Thought Divides Us All, Imprint Academic, 2014, pb, 136 pp, £9.95

Veteran anti-racist campaigner, teacher and film-maker Adrian Hart has watched as his cause, anti-racism, has been hijacked by successive governments in a manner that reminds this reader of James Delingpole’s Watermelons (2011) – where ‘green’ (environmental) problems were seized upon as excuses for (big-government) ‘red’ solutions.

The outline of his argument is that at the same time that society chose to purge itself of its racist edges (broadly coterminous with the emergence of the Macpherson Report, 1999), the UK government decided to use the report to justify an unparalleled increase in its own powers.

Hart notes that although we are drip-fed the failures of multicultural Britain by the media, Britain’s largest minority group is now the category formerly known as ‘mixed race’, showing that ethnic fusion is increasing, and perhaps more importantly, a rising proportion picking ‘English’ rather than the looser, baggier ‘British’ label on forms. Not only that, a Home Office Citizenship Survey of 2011 showed that whites were more likely to believe that racial prejudice had increased than the people who were supposedly experiencing it (by almost 25 per cent).

However this seemingly rosy picture did not suit the government narrative in 1999. Even though the Macpherson inquiry acknowledged that Doreen Lawrence said ‘I personally have never had any racism directed at me’, that a white witness noted that ‘the attack [on Stephen Lawrence] seemed motiveless and could have been levelled at me’, and that Detective Sergeant John Davidson believed ‘it was thugs attacking anyone, as they had done on previous occasions with other white lads’, the government decided to utilise public goodwill not only to implement much-needed institutional reform but to redefine racism according to what is going on in other peoples minds, a phenomenon Hart describes as the introduction of chaotic ‘third-party victimhood’.

This fantastically broad definition has enabled fantasy racism to displace the real thing. It is less worried about quashing real racism than enabling total control over ‘incorrect’ thought or behaviour. This tool is placed in the hands of the government by what seems to have been a legion of useful idiots. From Dr Oakley (a big player in the Macpherson Report) to Martin Jacques, who came curiously close to actual racism when he wrote in the Guardian in 2007 that racism is ‘constantly reproduced in each and every white citizen of [England]’.

The heroes of the book are usually immigrants resisting nonsense from above. Dr Tony Sewell insists that black underachievement comes far less from racist stereotypes and low expectations than from a cloying ‘victim morality’ generated by a PC culture that is eventually internalised. Arwa Mahdaawi notices the homogeneity (and racism?) of a ‘diversity’ that only recognises multiplicity in skin tones, not types of people, having gone on a civil service fast stream diversity internship programme, where:

“Despite the many shades of brown, I’m not sure we were a “diverse” bunch. We were uniformly articulate and educated. We hailed from the same five universities.”

Talking of education, the real teeth in the book are the parts where children are involved (Hart’s specialism as an ex-teacher). Lowlights include Essex council’s intimidation of a school suffering ‘too few’ racist incidents with a letter claiming ‘high levels of reported incidents are the result of good practice rather than the converse’ – a statement that comes dangerously close to suggesting that kids are naturally racist. The absurdity is stripped bare as Hart notes that:

“If [children] express an awareness of different skin colour, they are reflecting [racism]… if they do not remark on difference, they have been inculcated into a ‘colour blindness’ that is, itself, racist [because it suggests they have been subsumed into a white identity].”

This double bind shows how insincere the government is about tackling real racism. If this was not the case, the confrontation of these two ‘types’ of racism would have been resolved. The collision with no conclusion, however, allows for government control: it is the cage it can capture anybody in. And it is a power exercised even at the lowest levels of society.

Some of the book’s most disturbing passages recount how kids as young as three are being sent to the counselor or to the ‘pastoral team’. Here perhaps Hart could have highlighted how would-be racist epithets flying around the playground form evidence less of a core of race-hate, than the fact the terms have lost their sting and have in fact become lazy throwaway remarks, comments that thrive because they have been reduced to the stock repertoire.

Hart calls the cleavage between our non-racist society and a government that sees racism everywhere, the ‘reality-gap’. Citing Brian Barry, the left-wing philosopher, Hart reminds people that elites use divide and conquer techniques to keep the people subdued; that equality before the law has been inverted to mean all difference should be respected so that it can be used as a weapon; and to raise awareness of the rise of a dangerous therapeutic form of government that seeks to micromanage our emotions and thoughts, and, in the words of Kenan Malik ‘seal the people into ethnic boxes [so that government can] police the boundaries.’

And it is with people secure in their boxes that Hart discerns the end of a public sphere as a place where disagreements contend. Instead common sense is rejected in favour of an official arbitration that relies on procedures which would be comical if they were not so tragic. The overall tone of the book, however, isn’t tragic, quite the reverse. At the end the author announces:

“We have a choice. We can fear the nightmare vision of society in which racism lurks unwittingly just under the surface… OR we can embrace genuine diversity.”

HENRY HOPWOOD-PHILLIPS works in publishing

………

………………

Gender Studies, an Aberrant Ideology

Steve Moxon lets rip

Jacqueline Rose, Women in Dark Times, Bloomsbury, London, 2014, £20

Women in Dark Times by Jacqueline Rose is feminist cant of such imbecility as to be a leading candidate for the most risible non-fiction book of the year, or even decade.

Most glaringly, it is riven through with comprehensively discredited notions from Freud and other psychoanalysts in their un-falsifiable and therefore wholly non-scientific ‘theories’, revealing that Rose has not even the slightest knowledge of psychology or any science. And no wonder: scientific illiteracy is an essential prerequisite to maintain the empty lines of her argument. Indeed, she explicitly decries “reason”, positing instead that “confronting dark with dark might be the more creative path”. Rose tries to make out that “man’s rivalry with women” – itself a non-existent, merely politically supposed phenomenon (there being no such thing in biology as cross-sex dominance interaction) – is “because she once was, is still somewhere now, a rejected part of himself”. This non-scientific twaddle, cited as being from the psychoanalyst Melanie Klein, was discredited somewhere in the middle of the last century, along with ‘penis envy’, the ‘death instinct’, ‘repression’ and everything else Freud and his disciples ever came up with. Somebody needs to tell university humanities departments.

From the outset, there is the stark assertion of empty political shibboleths without any attempt whatsoever at justification: “We cannot make it only by asserting women’s right to equality”, Rose opines in the very first paragraph; in which she also claims that women’s knowledge is a new epistemology akin to some ancient mythic priesthood. Well, at least feminist special pleading is here put frankly. And she does concede that she can speak only for some women, though without pointing out that this is a tiny slither of the female sex; albeit indicating this well enough in her choice of a handful of rarefied individuals she considers emblematic women worthy of a chapter each. These, Rose supposes, are representative of female suffering that is “unseen”! Unseen! Since when was any female victimisation not the very centre of attention, together with various exaggerated or manufactured bogus forms of female victimisation? Never mind in instances of artistic or other fame, as is common to Rose’s ‘heroines’ here. It is male suffering which goes unseen: males are unable to seek help because they know they will not get a hearing and instead will be derogated; hence the extraordinary high rates of male compared to female suicide.

Rose’s exemplars are all supposed dire cases worthy of the label “survivor” – the standard giveaway charged misnomer – yet they are none of them any sort of victims of her ‘patriarchy’ bogey. Most are in no sense victims at all, but, on the contrary, successful if comparatively obscure contemporary artists. The remainder sustained ordinary damage and/or were caught up in grand upheavals that anyone and everyone succumbed to. Marilyn Monroe was passed between eleven different foster families before seeing her mother committed to a mental hospital. Rosa Luxemburg had risen from nowhere to hold court with the most famous communist leaders to express face-to-face severe criticism of them and their movements, that had she been male would have earned her execution long before she finally provoked that end (which, for her advocacy of mass slaughter, she well deserved in any case). And Charlotte Salomon had a family history of serious mental health issues, with her mother and two sisters all committing suicide; and as a German Jew was caught up with everyone else of her ethnicity/religion in the Nazi nightmare.

The heart of Women in Dark Times is where Rose gets away from her obscure artists and empty political or media pin-ups to look at ‘honour’ crime, but she gets this spectacularly wrong at the same time as unwittingly providing a window on the truth. [I say unwittingly, but it’s hard to see how she could be so blind, rather than wilfully addled by her quasi-religion.] Leaving aside that across cultures and through all history those on the receiving end of extreme violence in retribution for infidelity typically if not universally are men, yet ‘honour’ crime is explicitly defined in terms of only female victims; the instigators (rather than the mere proxies) are usually women — the family matriarchs or younger mothers. “One of the most disturbing aspects of these stories is the involvement of mothers in policing their daughters, and even on occasion in killing them”, Rose tellingly comments. “Purna Sen [of the LSE] sees such involvement by women as one of the distinctive features of honour crimes”. Rose cites cases of the target for violence being the male adulterer or both parties, and that the “mother can no longer hold her head”. That the male ‘honour’ killers are proxies of the instigators more than they are instigators themselves, and the ‘fall guys’ in the enterprise, is revealed in the following passage: “… the act is a matter of deepest regret, even as they are egged on, lauded and told to be proud. These young men, often chosen to enact the crime on the grounds that their youth will lead to a reduction of their sentence, mostly find themselves rejected and isolated by their families once in prison”.

It never crosses Rose’s mind that this phenomenon is not some ‘patriarchal’ [sic] imposition but is a female intra-sexual phenomenon which is supported by males inasmuch as they are duty-bound to do so given their civic role. Instead, Rose plucks out of thin air: “Honour is therefore vested in the woman but it is the property of the man”. On the very contrary, it is the ‘property’ of women; just as is Chinese foot-binding, female genital mutilation, and the various forms of face-veiling and body-shrouding (which pre-date and therefore are not from Islam). All of these cultural practices are similarly grounded in female intra-sexual competition for pair-bond partners. They clearly serve to indicate prospective fidelity or to dissuade girls/women who might be tempted to subvert a pair-bond. This is in the interests of high mate-value women, which in turn is in the collective interest of the reproductive group as a whole to maximise reproductive efficiency. [See my paper on human pair-bonding.]

Oblivious to any need to make a cogent case, Rose is at times wholly unguarded in her vacuity: (talking of women, of course) “we find it very hard to blame ourselves” – “No woman is ever as bad as her worst cliché”. Indeed, excruciatingly stupid clichés litter this entire tome. There’s even the utterly fatuous “the idealisation of women’s bodies can be a thinly veiled form of hatred (as we have seen in relation to Marilyn Monroe)”. Men adore women’s bodies yet this is somehow inverted to be “hatred”.

Given the hegemony of ‘identity politics’, expect Women in Dark Times to become a multi-part BBC TV series in due course. It’s just the sort of bull the BBC loves to endlessly recycle in the firm belief that eventually everyone will swallow it. They will not.

STEVE MOXON is the author of The Great Immigration Scandal and The Woman Racket.

………

…………….

First Total War

Frank Ellis confronts the dark side of modernity

Alexander Watson, Ring of Steel: Germany and Austria-Hungary at War, 1914-1918, Allen Lane, London, 2014, with maps, photos, notes, bibliography and index. ISBN 978-1-846-14221-5

Vielleicht opfern wir auch uns für etwas Unwesentliches. Aber unseren Wert kann uns keiner nehmen. Nicht wofür wir kämpfen ist das Wesentliche, sondern wie wir kämpfen. Dem Ziel entgegen, bis wir siegen oder bleiben. Das Kämpfertum, der Einsatz der Person, und sei es für die allerkleinste Idee, wiegt schwerer als alles Grübeln über Gut und Böse.[Ernst Jünger, Der Kampf als inneres Erlebnis]

Based on some valuable source material and clearly written, Ring of Steel is a worthy project with which to mark the one hundredth anniversary of the start of the Great War, though the author’s claim, even allowing for the circumscribing effect of ‘modern’, viz that – ‘This book is the first modern history to narrate the Great War from the perspectives of the two major Central Powers, Germany and Austria-Hungary’[1] – is exaggerated. No matter, Ring of Steel is a good and serious read, with the emphasis falling on how Germany and its Austro-Hungarian ally coped with the blockade – the ring of steel – that slowly strangled them during World War I and the tactical and strategic decisions taken by the Central Powers in order to seize the initiative from their two main opponents, Britain and France, in order to avoid defeat.

Although the American Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War provided some idea of the huge technological changes that had taken place in the prosecution of war in the latter half of the nineteenth century, offering pointers to how a European-wide conflagration might develop, by 1914, the start of the Great European Civil War, the destructive power of modern armies and navies, and eventually the first air forces, had exceeded the ability and imagination of military and civilian planners fully to comprehend the nature of the violence that they were now able to unleash. In fact, 1914 marked the start of a new type of war – total war – and by 1918 it was total: mass conscription; rationing (actual starvation in parts of the Central Powers); genocide (Armenia); rampant inflation; indifference to mass slaughter; government censorship; seizure of private assets; unrestricted submarine warfare (a disastrous German move); British naval blockade (of dubious legality as Watson argues); multiracial strife; ethnic cleansing and deportations; air raids; and towards the end a hideous influenza pandemic that cut down millions.

These outcomes were bad enough but as a result of the chaos of war and the ineptitude of the Tsarist government Lenin and his gangsters were able to seize power in Russia. From the misery of total war emerged a new type of state, the totalitarian state, the Soviet Union, based on the ideology of class war, red terror and striving for global domination. Moreover, after the war there were huge population displacements, especially of Germans; some 13 million were now outside the Reich’s borders. This would have been a gift to any nationalist politician, never mind someone as politically brilliant and ruthless as Hitler. Combined with the injustices of Versailles – Article 231 of the Versailles Treaty was deemed by the German delegation to be the “war-guilt clause” – starvation, war reparations and hyperinflation, this massive population displacement and the very real Bolshevik threat prompted a violent nationalist reaction in Germany out of which Hitler’s National-Socialist German Workers’ Party eventually emerged as the dominant faction and the serious contender for power.

One obvious conclusion derived from Ring of Steel is that the combat performance of the Austro-Hungarian component was massively weakened by racial and cultural diversity. By language, Germans, Magyars, Czechs, Slovaks, Ruthenes, Poles, Slovenes, Serbo-Croats, Romanians and Italians were all represented. The longer the war lasted the more this fragile unity was tested, the more ethnic loyalties asserted themselves, whereas inside Germany all the signs were that Germans whatever their political allegiances rallied, focusing to begin with on Tsarist Russia and then on Britain as the main enemy (encapsulated in the slogan: ‘Gott strafe England’).

The nation-wide commitment to maintain Burgfrieden according to which all political in-fighting was suspended while the war lasted had no real chance in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. To cite Watson: ‘The lack of an Austria-wide Burgfrieden also meant that bonds of solidarity strengthened within, rather than between, ethnicities’.[2] This confuses cause and consequence: it was the fissiparous nature of multiethnicity that ruled out any possibility of a Burgfrieden from the very beginning: diversity in adversity is emphatically not a strength. In fact, Watson more or less acknowledges the dangers of diversity in adversity: ‘The ethnic tensions and suspicions inflamed by the assassination [Emperor Franz Ferdinand] across the Habsburg Empire should have cast doubt on the unreasoned faith that armed conflict would somehow bring greater unity to a divided realm’.[3] In Germany, on the other hand, Prussian refugees, fleeing Russian terror, were welcomed, whereas Galician refugees met a hostile reception from Austrians. According to Watson this was due to the fact that ‘To a large degree, this reflected the more tenuous ties between (sic) peoples in a multi-ethnic empire compared with the solid “imagined community” of a modern nation state’.[4] To put this more forcefully, racial and cultural homogeneity strengthen bonds – surely obvious – racial and cultural heterogeneity weaken them, disastrously so in fact. It also strikes this reviewer as insulting to regard the state of Germany in 1914 or the tight-knit communities of Galician Jews as ‘imagined communities’. Jewish communities and the ancient nation states of England, France, Russia, China and Japan were not figments of the political imagination. These ancient nations embodied many centuries of shared blood, glory and shame. Nor could they just be “unimagined” – “deconstructed” in the jargon – and made not to exist. Despite his perhaps unwitting appeal to neo-Marxist “imagined communities”, the evidence, much of it cited by Watson himself, shows that multiethnic (multiracial) empires are highly unstable in moments of crisis. Syria and the murder and slaughter in Iraq are just the most recent examples.

Watson’s attempts to play down the patriotic fervour at the start of the war are not entirely convincing. The memoirs of Ernst Jünger – there are no references to Jünger or his work at all in Ring of Steel, an astonishing omission – leave little doubt about the patriotic fervour that gripped Germany and, for combatants such as Jünger, the sense of adventure offered by the start of war. The fact that there were very large anti-war meetings in Germany between 28th-30th July 1914 is all well and good but many of these socialist protestors went to war in the end. Watson, having tried to play down the upsurge of war and patriotic fervour, records the remarks of the Berlin police chief who noted that people, members of the SPD (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands), who only recently were cheering the Internationale in protest meetings now bubble over with patriotism.[5] Germans who supported the Social-Democrats went to war for Germany because blood is thicker than water; because Germany despite all the Marxist propaganda about international worker solidarity meant more to them than love of the English and French proletariat. That is as it should be.

Watson does, however, show a good grasp of the qualities that made the German Army so formidable. First, the intellectual standards required for its senior officers and planners were much higher than those in other armies, the British appearing amateurish by comparison. One of the main doctrines of the German army, one that was carried over into World War II, was Auftragstaktik. Watson translates this as ‘mission tactics’, whereas I would prefer ‘mission-led command’. The critical thing about Auftragstaktik is that subordinate commanders were given a mission and then required to solve it. German junior leaders, unlike in other armies, were not micro-managed. They were expected to make decisions, show initiative, solve problems and, if opportunities arose, to inflict damage on the enemy. For some bizarre reason Watson characterises the doctrine of Auftragstaktik as ‘infamous’[6] when in fact it was one of the great strengths of the German army and, by contrast, underlined the distinct lack of trust felt by British commanders in their subordinates. The German cadre of non-commissioned officers, unlike their British counterparts, constituted an élite professional body, often discharging duties which in other armies would be the preserve of officers. The German emphasis on initiative at all levels of command meant that Western propaganda which depicted German soldiers as unthinking robots was very wide of the mark. On the subject of the German navy there can be no doubt that Germans felt an immense pride in the German navy and the challenge it represented to Britain’s Royal Navy. Yet, bottled up in harbour after the battle of Jutland, sailors in the German fleet proved to be very susceptible to the ideas of the Russian revolution, becoming something of a liability.

One of the most important aspects to this book and one that poses a severe challenge to a lot of German historiography on World War I (and World War II) is that Watson documents the savagery of the Tsarist army on German territory at the start of the war. This is important for German planning prior to the start of Barbarossa in 1941 since Tsarist-Russian behaviour scarred German memory and fed German fears before the start of Barbarossa about the way German prisoners would be treated were they captured by the Red Army. Especially striking is how Tsarist-Russian behaviour anticipates the way the Red Army and the NKVD would behave after 1918, though, of course, the state terror perpetrated by the organs of the NKVD dwarfed anything carried out by Tsarist Russia.

What is not widely recognised even today is that Tsarist-Russian plans for Galicia were clearly racial and that the war was regarded as one for racial unity. There are, as Watson notes, though with some qualification, clear parallels with Nazi plans in 1941: ‘While Tsarist plans did not share the Nazis’ genocidal intent, they placed racial considerations at the centre of the region’s future, contravened international law, and caused tremendous suffering to hundreds of thousands of people in 1914-15’.[7] Allenstein, some 50 kilometres from Prussia’s south-eastern border, was one of the first Prussian towns to be occupied by the Russians (The occupation is also dealt with by Solzhenitsyn in August 1914 (1971 & 1989) and Watson would have found it useful to have examined Solzhenitsyn’s account). On entering Allenstein, the Russian invaders demanded huge amounts of food from the German inhabitants: 120,00 kilograms of bread; 6,000 kilograms of sugar; 5,000 kilograms of salt; 3,000 kilograms of tea; 15,000 kilograms of grits/rice; and 160 kilograms of pepper. Compared, however, with the immense damage inflicted by the Russians on other Prussian towns and villages, Allenstein was lucky. In other areas, the Russian commander, General Rennenkampf, let it be known to the civilian inhabitants that attacks on Russian troops would be punished mercilessly regardless of sex or age. He also threatened collective punishment, a clear violation of international law. Watson describes the Russian state of mind during this invasion: ‘There were also paranoid accusations of armed resistance. Francs tireurs were rumoured to rove the countryside on motorcycles and bicycles, German soldiers in mufti to be mingling among the population, and seemingly innocuous civilians to be plotting to poison unsuspecting Tsarist soldiers’.[8] Moreover, the fact that cycles were so rare in poverty-stricken Russia, Germans on bikes were assumed to be in the German Army or working for it.

As far as the Russians were concerned, security mandated mass deportations. To quote Watson: ‘The Russian Army’s most distinctive and extensively used tool of oppression was deportation. New Field Regulations issued at the end of July 1914 granted the Tsarist army unlimited authority over the population in war zones, including this power of removal. Whether in international law it was legal was more ambiguous, for its use had not been foreseen’.[9] In fact, these New Field Regulations anticipate any number of German decrees and orders in World War II and in a foretaste of what the NKVD would do in the Soviet period hundreds of thousands of ethnic Germans were deported from border zones. Dumped on the Volga or between the Volga and Urals, those that were deported endured untold misery and suffering. Yet, as Watson notes, ‘The thousands of East Prussians deported to the Volga were dwarfed by the hundreds of thousands of people from Russia’s own German minority cleared from western regions’.[10] Russian behaviour stiffened German resistance. In Watson’s words: ‘For the rest of the conflict, East Prussia would stand as an awful warning of the consequences of allowing enemy troops onto German soil. The memories and myths of the invasions would retain their ability to mobilize and unify the German people long after all danger from the Russians had passed’.[11] Contemporary German historians seem very reluctant to acknowledge that such memories may have played a role in determining German attitudes towards the Soviet state.

On 16th July 1941, Hitler, conferring with his senior planners on the progress of the Russian campaign, stated that ‘The vast area must, of course, be pacified as quickly as possible. The best way for this to happen is that any person who so much as looks askance is shot dead’. All the evidence cited by Watson shows that the Cossack units in the Tsarist army behaved in exactly the same way. These units were also violently anti-Semitic and when they engaged in Jew baiting, locals – Poles and Ruthenian peasants – took part. Again, the parallel with what would happen after the Germans invaded the Soviet Union is striking, especially in the Baltic States. In the Russian occupation zone in Galicia the Russian Governor General, Count Georgii Bobrinskii, even tried to russify the zone. There were more deportations and the Russian language was imposed. Ruthenes were encouraged by the Russians to loot Polish property and estates but the people who suffered the most from these dispossessions and baiting were – once again no surprise here – Galicia’s long-suffering Jews. As the Russians were forced out by the Germans, they, the Russians, pursued a scorched-earth policy. Worse still, as the Tsarist army retreated, it deported 3.3 million civilians. Watson notes the German reaction: ‘Advancing into the deliberately devastated landscape, encountering scattered, desperate and dispossessed inhabitants, German soldiers could be left in no doubt that they faced an evil empire’.[12] Indeed, and these memories persisted, festered and were exploited by nationalist politicians.

The biggest threat to the ability of the Central Powers to prosecute a long war was the British naval blockade. The reduction in foodstuffs had to be made good and this prompted a German administrative regime in the eastern territories, which was intended to maximise the sequestering and production of agricultural products and to ensure absolute food security. For example, Lithuania and Courland were envisaged as areas of German expansion – they were referred to as Ober Ost – and were ruled over, to begin with, by Erich Ludendorff, then the chief of staff on the Eastern Front. The whole concept of Ober Ost clearly anticipates later Nazi plans for the agricultural exploitation of the occupied Soviet territories, as laid out by Hermann Göring, though to be fair to Ludendorff there was no intention to starve people to death, as was clearly provided for in Nazi plans. A pertinent question here, it seems to me, is whether the British starvation blockade aimed primarily against Germany in World War I played any part in inspiring NS policies of mass exploitation of Soviet territories in WW II and a willingness to countenance mass starvation.

Lessons to be drawn from the Great European Civil War are, firstly, that it swept away all hopes that major wars were a thing of the past and, secondly, that any kind of internationalism, in the first instance, global socialism – and currently we-are-the-world multiculturalism – would prevent wars. Various manifestations of socialism actually caused wars. One hundred years on, there is more than enough uncertainty, latent instability, danger, and actual conflict in Europe and elsewhere to reject the perverse and dangerously naive view of the world peddled by EU politicians that all problems and conflicts are amenable to discussion. The lesson of history is quite clear: when states see their vital interests threatened, they resort to force or threaten the use of force. Russian moves against Ukraine, above all Crimea, and the Chinese-Japanese territorial dispute, are just the latest examples. Rest assured, there will be many more to come.

© Frank Ellis 2015

Dr Frank Ellis is an historian and author

[1] Ring of Steel, p.1

[2] ibid., p.96

[3] ibid., pp.60-61

[4] ibid., p.203

[5] ibid., p.84

[6] ibid., p.109

[7] ibid., p.162

[8] ibid., p.172

[9] ibid., p.177

[10] ibid., p.195

[11] ibid., p.181

[12] ibid., p.268

……….

………………..

The Rise of the Dominatrix

Derek Turner’s take on Charles Moore’s biography of Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Thatcher: Not for Turning, Charles Moore, London: Allen Lane, 2013, 859 pp

When Margaret Thatcher died last April, the obsequies were at times almost drowned out by vitriolic voices celebrating her demise. There were howls of joy from old enemies, street parties, and a puerile campaign to make the Wizard of Oz song, “Ding, Dong, The Witch is Dead!” the top-selling pop single (it failed, narrowly). The extravagant hatred evinced by some shocked some, but it was in a way an entirely suitable send-off for a woman who always loathed ‘consensus’. She may be the last Conservative whose demise will evoke more than a yawn.

This is former Spectator and Daily Telegraph editor Charles Moore’s first book, but it is an assured production, steeped in its subject, judicious in its handling of history, coloured by his journalistic instinct for revealing and amusing anecdotes. In this first of two volumes, he follows his heroine from birth up to what “may well have been the happiest moment in her life” – the October 1982 victory celebrations after the recapture of the Falklands. His heroine she may have been – and this is why she approached him to be her biographer, on the understanding that publication would be posthumous, and interviewees knew she would never read what they had said – but he maintains critical distance. There are 54 pages of footnotes referring to innumerable interviews, and a seven page bibliography, assembled over 16 years of what must have been at times an all-engrossing project, whilst incidentally editing Britain’s best-selling broadsheet newspaper. We will need to wait until the companion volume, Herself Alone, to get Moore’s assessment of her legacy, but for now, Not for Turning equips us admirably to understand what she was like as person and politician, why she was the way she was, and suggest why she would succeed in many ways, yet fall short in others.

Moore’s researches were at times made more arduous by his subject, a naturally private person who was always, as he reflected in the Daily Telegraph after she died, “keen to efface the personal”. Her memoirs gloss over emotions or incidents about which we would like to know very much more, or lend “Thatcherism” greater coherence in retrospect than it possessed. But luckily she was intrinsically honest, and Moore early learned to read subtle signs – “All politicians often have to say things that conceal or avoid important facts. She certainly did this quite often; but she did it with a visible discomfort which often undermined her own subterfuge.”

This complex personage pushed into the world in 1925, and lived above a commercial premises in Grantham, Lincolnshire, a town even now a byword for provincialism (despite having been Isaac Newton’s hometown). It was one of two grocery shops run by her father Alfred Roberts, who when he wasn’t selling sausages to Midlandian burghers was Mayor and a Methodist lay preacher. “If you get it from Roberts’s – you get the BEST!” was the shops’ slogan, and her parents’ rectitude, work ethic, and attention to detail would stay with their daughter.

School was preparation for a life of application. A contemporary remembered – “She always stood out because teenage girls don’t know where they’re going. She did.” She unsurprisingly excelled in declaiming from sturdily middle-brow poets – Tennyson, Longfellow, Kipling, Whitman. Serious, too, was her sojourn in Somerville, regarded as the cleverest of the female colleges in Oxford, where she read Chemistry and thrived even under a Leftist principal.

The young Margaret Roberts, notwithstanding the pervasive progressive miasma, was already obstinately Conservative, although she had not yet refined her particular brand. She joined the Oxford Union Conservative Association (OUCA) and became its president, and co-author of a pamphlet destined to be combed over by obsessives in later years. At that time, the Conservative Party was a mass movement, and a means of social mingling, and many joined for social as much as political reasons, or simply to find a spouse of the right Right type. Moore suggests that she likewise saw OUCA as an “opening of the door”. She took elocution lessons, and met as many influential people as possible, always inveigling herself somehow onto the top table at dinners. Yet her letters to her parents and older sister Muriel are often apolitical, rarely even mentioning the War, unexpectedly spotted with spelling mistakes, full of family, clothes and rare romantic interests, the latter discussed in briskly British terms. When she first met Denis, her husband-to-be, she told Muriel that he was “a perfect gentleman. Not a very attractive creature”. (He remembered her almost equally coolly – “a nice-looking young woman, a bit overweight”.)

After graduation, she worked in industry, and in 1950 stood for Parliament for the first time, in the solid Labour seat of Dartford in Kent. She conducted a dynamic campaign, characterized by her contribution to a debate hosted by the United Nations Association, which featured her Labour opponent Norman Dodds and other speakers even further Left: “I gave them ten minutes of what I thought about their views! As a result Dodds wouldn’t speak to me afterwards and Lord and Lady S. [Strabolgi – an old Scottish title Italianized in the 16th century] went off without speaking as well.” She made an impressive 6,000 dent in the Labour majority. It is characteristic that at the count she told her activists that the next campaign would start the following morning.

She married Denis in 1951, the start of a quietly contented partnership that lasted until he died in 2003. As well as his earning capacity and a business brain useful whenever his wife needed to comprehend company documents, he brought to their alliance some social status, a large fund of commonsense, and a willingness (even now rare for men) to take a back seat. Performing household tasks – she cooked when she could, and enjoyed tidying (an everyday application of what Edward Norman called her “pre-existing sense of neatness and order in society”) – assuaged the faint guilt she clearly felt at being something of a Bluestocking.

Needing to earn more money, she trained for and practised at the Bar, and the experience added to her near-mystical respect for law of all kinds. She later systematized this passion for precedents – “As a Methodist in Grantham, I learnt the laws of God. When I read chemistry at Oxford, I learnt the laws of science, which derive from the laws of God, and when I studied for the Bar, I learnt the laws of man.” Between work and family, she politicked tirelessly, resenting even holidays as wasted time. (There is a telling photo of her in this book, on holiday in the Hebrides in 1978, walking in business clothes along a beach, staring at her watch.)